← Back to Reviews

in

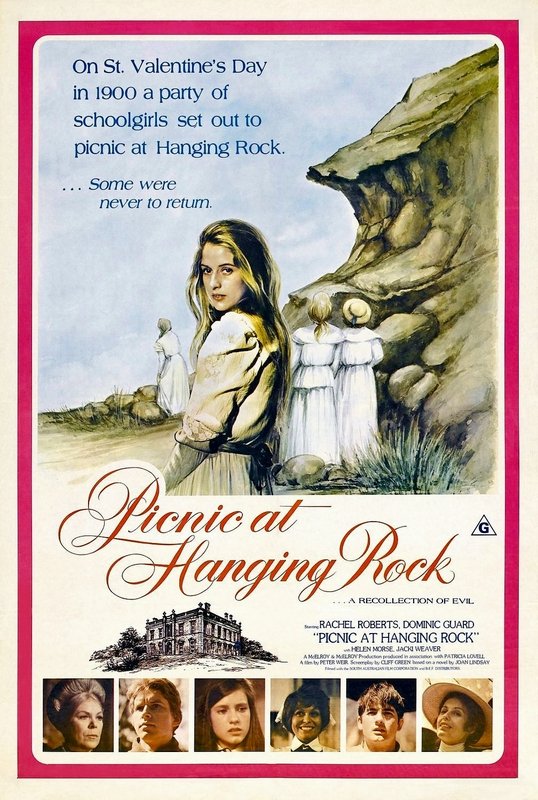

Picnic at Hanging Rock - 1975

Directed by Peter Weir

Written by Cliff Green

Based on a novel by Joan Lindsay

Starring Rachel Roberts, Dominic Guard, Helen Morse, Margaret Nelson

Anne-Louise Lambert, Vivean Gray & Jacki Weaver

This review contains spoilers

I have to admit that even after all these years, I'm still as mesmerized as I ever was when watching Picnic at Hanging Rock. I mean, after all, the film itself has to be more than just it's central mystery. To fascinate us, it needs to get us into the right mood, and to be worth remembering it has to be more than just a riddle without a solution - for the casual viewer though, Picnic's more serene contemplations are somewhat drowned out (at times) by it's more haunting qualities. Nature, time, the connection we have to our environment, and the odd contrast that British culture had (and still has) when viewed against the backdrop of such a harsh, unrelenting, alien landscape are explored. All of these themes are woven tightly together in both Joan Lindsey's novel, and the Peter Weir film. Looming above it all is the vanishing - three students and one teacher from Mrs. Appleyard's College for Young Ladies, of whom only one would ever be found. The events surrounding this all heighten the ethereal qualities of this occurrence.

The year is 1900, it's Saint Valentine's Day, and an annual picnic at Hanging Rock for some of the student's at Mrs. Appleyard's College is in the offing. Sara (Margaret Nelson), perpetually bullied by Mrs. Appleyard herself (Rachel Roberts) and in love with fellow student Miranda (Anne-Louise Lambert) is not allowed to go. Shepherding the young girls are Miss Greta McCraw (Vivean Gray) and Mlle. de Poitiers (Helen Morse). The hot sunny day lulls everyone into a dreamy state, and four girls decide to climb to the top of Hanging Rock - Miranda, Marion (Jane Vallis), Irma (Karen Robson) and Edith (Christine Schuler). Two nearby young men, Michael Fitzhubert (Dominic Guard) and Albert Crundall (John Jarratt) watch them as they go. All girls except Edith fall into a kind of trance, and as they slowly walk out of view, Edith screams and runs to the group picnicking below. When the whole group returns to the college, well after the 8pm deadline, Mrs. Appleyard demands to know why - and as it happens, the three students along with Mrs. McCraw have disappeared, without a trace.

Yes, there's a Mary Celeste vibe to most of the proceedings in Picnic at Hanging Rock - the easiest solution would be to say that perhaps those missing have fallen into an unseen cavity in the rock formations - there are many in the area - but there's still too much that doesn't make sense. Why did Edith return screaming, and why does she remember nearly nothing of what happened? Why did Mrs. McCraw leave the main group, unseen, and where did she go? What further mystifies everyone is the fact that a desperate Michael searches for the girls, and finds one of them - Irma, who can remember nothing of her ordeal, and can't explain how she survived as long as she did exposed to the elements, with no water at hand. In the end the flow-on effects of the bizarre mystery spread to Mrs. Appleyard's College. Parents decide not to renew enrollment, and Mrs. Appleyard, now drinking heavily, sees her finances spiral into the dust. Then there's poor Sara - who apparently commits suicide by jumping off the roof of the mansion, or else, as hinted at in the film and book, perhaps she's murdered by Appleyard, whose mental health is deteriorating.

There are solutions out there - Joan Lindsay's publisher revealed that when the author submitted the work, there was an 18th and final chapter which described what happened - but she was persuaded that the book was much better without it. After Lindsay died, this final chapter was finally published amongst a collection of essays as "The Secret of Hanging Rock" - it describes a veritable acid trip, with space, time and form all in flux, but I don't consider it a definitive ending to the story. That chapter was excised, and as such the story is as it is. You can't just add a chapter 20 years later - or at least you can, but it can't turn back time and become an everlasting part of what was. The movie, as well (in a very fitting way) has a conclusion which was left out in almost identical circumstances. This was an adaptation of part of the book - in the movie's excised last scene, when Mrs. Appleyard has reached her nadir, she travels to Hanging Rock herself, and kind of goes through what the girls did, or at least tries to. While there, she looks through the rock and sees Sara - and then we find out through narration that Appleyard's body was found at Hanging Rock, and it was presumed she fell. As it is right now, the film ends with Appleyard staring ahead - broken, and without hope of rescue.

So, we have the creepy vibe - but what is it about the film that makes it endure? I always think about those bright white dresses the girls are wearing, and the way they contrast with the natural surrounds of Hanging Rock. All white suggests some kind of virginal imagery - and the fact that this happens on Saint Valentine's Day furthers the whole aspect of "awakening love". For Australians though, it's also a very weird sight. Valentine's Day means February the 14th - and that means an Australian summer. You do not want to be wearing corsets, long dresses, stockings, undergarments belts etc. when you go exploring rocky outcrops during an Australian summer. It doesn't look like the girls belong there, at all. It's an extreme contrast - but as the three who disappear explore onwards they discard shoes and stockings so they can make direct contact with the rock itself. Instead of pretending to be in Victorian England, the girls are communing with nature for the first time - and the Australian outback is a haunting and ancient place. They don't belong - and before long, they cease to exist.

The cinematography was handled by an Australian great - Oscar winner (for Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World) Russell Boyd. Boyd had talent, and it shows throughout Picnic at Hanging Rock - the way he makes the rock itself loom over all who go near it, and the mysterious quality he lends the place through his use of natural lighting (especially during the picnic itself, which was filmed day after day at exactly the right time) and movement. Adding to the potent mixture of nature and perception is the editing - credited to lesser light Max Lemon. There are so many great fading dissolves and transitions which include flocks of birds, the rock, and the angelic faces of the girls. What would it be without the panpipe pieces by the Romanian folk musician Gheorghe Zamfir though? The film's musical accompaniment is part of Australian film folklore - and as a whole, the score is one of the greatest in film history. It's varied, and when we're not hearing the music that plays while the girls ascend (composed by Bruce Smeaton), or the panpipes, you're probably hearing Beethoven, Bach or Mozart. Everything fits every moment - creepy or luscious, to a degree of absolute perfection.

I can't fully put my feelings for Picnic at Hanging Rock into words - as I grew up, it got under my skin, and stayed there. In Australia, you'll read the novel at some stage in high school, and that's where I read the 18th chapter as well, which had just been published the same year we read it in class. As a little kid, it sounds and looks boring - all period dress, and pertaining to be about a picnic? I actually thought, as a little one, that this was a film about a pleasurable picnic - I've known the truth for a much longer time, though I never knew the film had an extended ending which was cut from it - I only saw that for the first time recently, and as good as the ending is, the part that was cut isn't bad. I agree with the decisions made though - the ending this film has is just right. As I try to explain, all I say sounds fragmentary - and maybe that's because I'm trying to convey many things at once - a sense of awe connected to a mystery, and a sense of recognition when it comes to the clash of British dress, architecture and custom that still sticks out like a sore thumb side-by-side with a country that's rough and harsh. The manicured lawns, peacocks and fancy furniture - just yards away from brown dead grass, lizards and dry dust. Picnic at Hanging Rock is also about our relationship with nature - and specifically an alien one to white people.

I'd really like to go one day - they say Hanging Rock really does have a haunting feeling about it. I've felt that feeling before. A brooding, mysterious whisper of the unknown. Miranda opens Picnic at Hanging Rock with "What we see and what we seem are but a dream, a dream within a dream" - paraphrased from an Edgar Allan Poe poem. It speaks to central mysteries about existence, thought, and our connection to our environment. If you're of European descent, then you're reminded every day that you weren't born for what Australia has in store for you - but just as with the girls in this film, it hypnotises you, and draws you in. Trust me - enough people have disappeared because of that allure. I can't then, end this without at least mentioning Aboriginal spiritual beliefs and their concept of "The Dreamtime" and Dreaming - which they've had as part of their culture for up to 65,000 years. Weir would directly tackle that with his next film, the equally haunting classic The Last Wave. It's all a part of what makes A Picnic at Hanging Rock enduringly special for Australians, and an equally beloved film for many overseas.

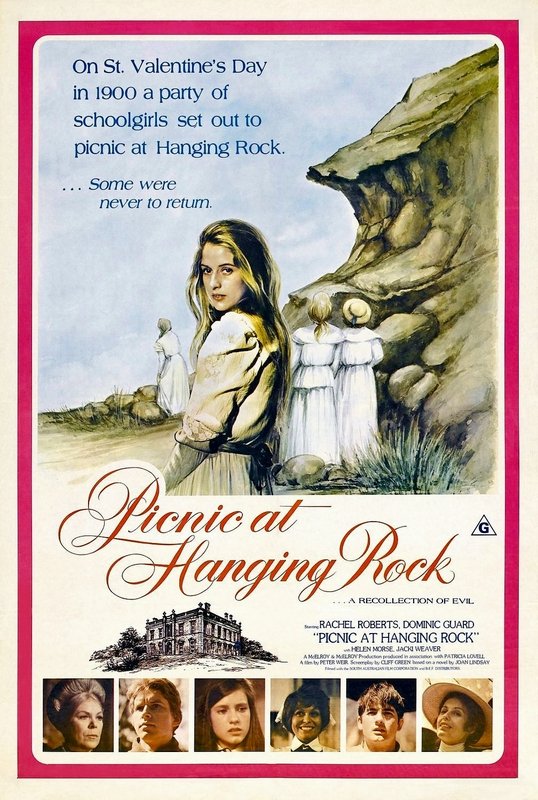

Picnic at Hanging Rock - 1975

Directed by Peter Weir

Written by Cliff Green

Based on a novel by Joan Lindsay

Starring Rachel Roberts, Dominic Guard, Helen Morse, Margaret Nelson

Anne-Louise Lambert, Vivean Gray & Jacki Weaver

This review contains spoilers

I have to admit that even after all these years, I'm still as mesmerized as I ever was when watching Picnic at Hanging Rock. I mean, after all, the film itself has to be more than just it's central mystery. To fascinate us, it needs to get us into the right mood, and to be worth remembering it has to be more than just a riddle without a solution - for the casual viewer though, Picnic's more serene contemplations are somewhat drowned out (at times) by it's more haunting qualities. Nature, time, the connection we have to our environment, and the odd contrast that British culture had (and still has) when viewed against the backdrop of such a harsh, unrelenting, alien landscape are explored. All of these themes are woven tightly together in both Joan Lindsey's novel, and the Peter Weir film. Looming above it all is the vanishing - three students and one teacher from Mrs. Appleyard's College for Young Ladies, of whom only one would ever be found. The events surrounding this all heighten the ethereal qualities of this occurrence.

The year is 1900, it's Saint Valentine's Day, and an annual picnic at Hanging Rock for some of the student's at Mrs. Appleyard's College is in the offing. Sara (Margaret Nelson), perpetually bullied by Mrs. Appleyard herself (Rachel Roberts) and in love with fellow student Miranda (Anne-Louise Lambert) is not allowed to go. Shepherding the young girls are Miss Greta McCraw (Vivean Gray) and Mlle. de Poitiers (Helen Morse). The hot sunny day lulls everyone into a dreamy state, and four girls decide to climb to the top of Hanging Rock - Miranda, Marion (Jane Vallis), Irma (Karen Robson) and Edith (Christine Schuler). Two nearby young men, Michael Fitzhubert (Dominic Guard) and Albert Crundall (John Jarratt) watch them as they go. All girls except Edith fall into a kind of trance, and as they slowly walk out of view, Edith screams and runs to the group picnicking below. When the whole group returns to the college, well after the 8pm deadline, Mrs. Appleyard demands to know why - and as it happens, the three students along with Mrs. McCraw have disappeared, without a trace.

Yes, there's a Mary Celeste vibe to most of the proceedings in Picnic at Hanging Rock - the easiest solution would be to say that perhaps those missing have fallen into an unseen cavity in the rock formations - there are many in the area - but there's still too much that doesn't make sense. Why did Edith return screaming, and why does she remember nearly nothing of what happened? Why did Mrs. McCraw leave the main group, unseen, and where did she go? What further mystifies everyone is the fact that a desperate Michael searches for the girls, and finds one of them - Irma, who can remember nothing of her ordeal, and can't explain how she survived as long as she did exposed to the elements, with no water at hand. In the end the flow-on effects of the bizarre mystery spread to Mrs. Appleyard's College. Parents decide not to renew enrollment, and Mrs. Appleyard, now drinking heavily, sees her finances spiral into the dust. Then there's poor Sara - who apparently commits suicide by jumping off the roof of the mansion, or else, as hinted at in the film and book, perhaps she's murdered by Appleyard, whose mental health is deteriorating.

There are solutions out there - Joan Lindsay's publisher revealed that when the author submitted the work, there was an 18th and final chapter which described what happened - but she was persuaded that the book was much better without it. After Lindsay died, this final chapter was finally published amongst a collection of essays as "The Secret of Hanging Rock" - it describes a veritable acid trip, with space, time and form all in flux, but I don't consider it a definitive ending to the story. That chapter was excised, and as such the story is as it is. You can't just add a chapter 20 years later - or at least you can, but it can't turn back time and become an everlasting part of what was. The movie, as well (in a very fitting way) has a conclusion which was left out in almost identical circumstances. This was an adaptation of part of the book - in the movie's excised last scene, when Mrs. Appleyard has reached her nadir, she travels to Hanging Rock herself, and kind of goes through what the girls did, or at least tries to. While there, she looks through the rock and sees Sara - and then we find out through narration that Appleyard's body was found at Hanging Rock, and it was presumed she fell. As it is right now, the film ends with Appleyard staring ahead - broken, and without hope of rescue.

So, we have the creepy vibe - but what is it about the film that makes it endure? I always think about those bright white dresses the girls are wearing, and the way they contrast with the natural surrounds of Hanging Rock. All white suggests some kind of virginal imagery - and the fact that this happens on Saint Valentine's Day furthers the whole aspect of "awakening love". For Australians though, it's also a very weird sight. Valentine's Day means February the 14th - and that means an Australian summer. You do not want to be wearing corsets, long dresses, stockings, undergarments belts etc. when you go exploring rocky outcrops during an Australian summer. It doesn't look like the girls belong there, at all. It's an extreme contrast - but as the three who disappear explore onwards they discard shoes and stockings so they can make direct contact with the rock itself. Instead of pretending to be in Victorian England, the girls are communing with nature for the first time - and the Australian outback is a haunting and ancient place. They don't belong - and before long, they cease to exist.

The cinematography was handled by an Australian great - Oscar winner (for Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World) Russell Boyd. Boyd had talent, and it shows throughout Picnic at Hanging Rock - the way he makes the rock itself loom over all who go near it, and the mysterious quality he lends the place through his use of natural lighting (especially during the picnic itself, which was filmed day after day at exactly the right time) and movement. Adding to the potent mixture of nature and perception is the editing - credited to lesser light Max Lemon. There are so many great fading dissolves and transitions which include flocks of birds, the rock, and the angelic faces of the girls. What would it be without the panpipe pieces by the Romanian folk musician Gheorghe Zamfir though? The film's musical accompaniment is part of Australian film folklore - and as a whole, the score is one of the greatest in film history. It's varied, and when we're not hearing the music that plays while the girls ascend (composed by Bruce Smeaton), or the panpipes, you're probably hearing Beethoven, Bach or Mozart. Everything fits every moment - creepy or luscious, to a degree of absolute perfection.

I can't fully put my feelings for Picnic at Hanging Rock into words - as I grew up, it got under my skin, and stayed there. In Australia, you'll read the novel at some stage in high school, and that's where I read the 18th chapter as well, which had just been published the same year we read it in class. As a little kid, it sounds and looks boring - all period dress, and pertaining to be about a picnic? I actually thought, as a little one, that this was a film about a pleasurable picnic - I've known the truth for a much longer time, though I never knew the film had an extended ending which was cut from it - I only saw that for the first time recently, and as good as the ending is, the part that was cut isn't bad. I agree with the decisions made though - the ending this film has is just right. As I try to explain, all I say sounds fragmentary - and maybe that's because I'm trying to convey many things at once - a sense of awe connected to a mystery, and a sense of recognition when it comes to the clash of British dress, architecture and custom that still sticks out like a sore thumb side-by-side with a country that's rough and harsh. The manicured lawns, peacocks and fancy furniture - just yards away from brown dead grass, lizards and dry dust. Picnic at Hanging Rock is also about our relationship with nature - and specifically an alien one to white people.

I'd really like to go one day - they say Hanging Rock really does have a haunting feeling about it. I've felt that feeling before. A brooding, mysterious whisper of the unknown. Miranda opens Picnic at Hanging Rock with "What we see and what we seem are but a dream, a dream within a dream" - paraphrased from an Edgar Allan Poe poem. It speaks to central mysteries about existence, thought, and our connection to our environment. If you're of European descent, then you're reminded every day that you weren't born for what Australia has in store for you - but just as with the girls in this film, it hypnotises you, and draws you in. Trust me - enough people have disappeared because of that allure. I can't then, end this without at least mentioning Aboriginal spiritual beliefs and their concept of "The Dreamtime" and Dreaming - which they've had as part of their culture for up to 65,000 years. Weir would directly tackle that with his next film, the equally haunting classic The Last Wave. It's all a part of what makes A Picnic at Hanging Rock enduringly special for Australians, and an equally beloved film for many overseas.