← Back to Reviews

in

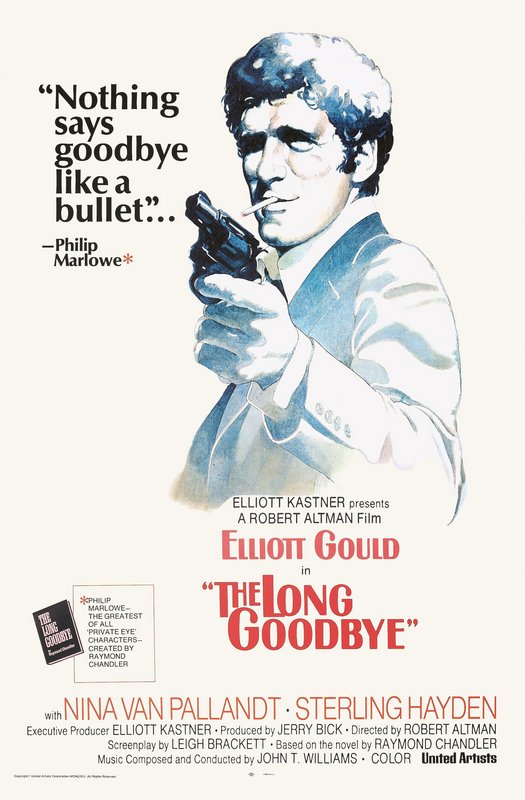

The Long Goodbye - 1973

Directed by Robert Altman

Written by Leigh Brackett

Based on the novel "The Long Goodbye" by Raymond Chandler

Starring Elliott Gould, Nina van Pallandt, Sterling Hayden, Mark Rydell

Henry Gibson & Jim Bouton

The longer you look at The Long Goodbye the more remarkable it seems, and the better sense you get of what you should be focusing on. In a neo-noir film based on a 1953 Raymond Chandler novel you'd think it would be the mystery - but this is more Robert Altman movie than Raymond Chandler story - character, atmosphere and a heady blend of themes create a work of art far from your typical noir story. Elliott Gould's Philip Marlowe becomes a private investigator from the 1950s trapped in the 1970s - and many questions remain ambiguously unanswered. Chandler's Long Goodbye has been infected by a different time, with different moralities. The ever-smoking, wisecrack-master washes through a world where topless, acid-dropping yoga enthusiasts work out opposite his apartment, hoodlums scar their lovers to make a point and truth becomes harder and harder to grasp. It's a world so changed that Marlowe has become a kind of child-like, innocent spectator - loyal to his friends and pets to the last, at a time when loyalty has gone extinct.

During a sleepless night, after trying to please his fussy cat, Philip Marlowe is visited by his only friend, Terry Lennox (Jim Bouton) who is sporting some impressive wounds on his cheek. Lennox speaks of having had a massive fight with his wife, and asks to be driven to Tijuana. The next day the police come looking for Marlowe - it seems that Terry has actually murdered his wife, and until Marlowe gives the cops information they'll hold him as an accessory. When Terry's body is found in an apparent suicide, they let Marlowe go - but the private investigator is sure that Terry is innocent - he knows him too well. In the meantime, he gets a job offer from an Eileen Wade (Nina van Pallandt) whose husband, Roger (Sterling Hayden) has gone on another bender and is missing. Marlowe tracks down a Dr. Verringer (Henry Gibson) who is trying to extort money from Roger, and brings him home. He's also visited by gangster Marty Augustine (Mark Rydell) who threatens to kill Marlowe unless he recovers the $350,000 that Terry took with him the night he went to Tijuana. When Roger commits suicide, and Marlowe finds out that he may have killed Terry Lennox's wife, he begins to suspect that Terry's suicide is not what it seems, and heads to Tijuana to chase down the truth.

Many questions remain unanswered, even after the big, dramatic reveal at the end of the film. Screenwriter Leigh Brackett really made the story her own - she'd previously written the screenplay for The Big Sleep, which featured Humphrey Bogart as Marlowe, and her surprise ending along with other quirks caught Altman's eye and imagination. He made sure that he wouldn't be forced to change these aspects of her screenplay, and this is how we got the Long Goodbye we have - a film which simply grows and grows in stature as the decades pass. On it's initial screenings, touted as being a straight noir/mystery/detective story, audiences were mystified and upset - it was then that the studio executives and distributors realised they had something different on their hands. It wasn't straightforward. That's the crux of this movie - you can't approach it like that, because the heart and soul of the film is in what it captures thematically onscreen. The loyal and bewildered Marlowe, the world he inhabits and the characters that contribute to the concoction of a strange Los Angeles society where morals and mores have shifted. For this, Elliott Gould gives what is perhaps the greatest performance of his career - for good reason, for his career was nearly over and he needed this.

Behind the lens, once again, Altman had cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond doing the director of photography work. Zsigmond had been with Altman on McCabe & Mrs. Miller and Images - Altman once again taking advantage of Zsigmond's proclivity to "flash" the negatives he'd use - exposing them to sunlight so they'd fade a little and turn bright colours into more subdued pastels, darkening the image. It creates the kind of atmosphere that seems to send 1970s L.A. back into the 40s and 50s in visual feel. He also demanded that the camera never rest or be static - it doesn't mean that we're careening all over the place or constantly in motion, but you'll notice that we're never completely still, and even static shots have a little bit of sway and movement to them - along with a little zoom, which shows up often. It does give the impression of being inside the picture. There's also a lot of reflectino and obfuscation. Altman has his own, recognizable visual style by this point in his filmmaking career, and The Long Goodbye is very much a part of his 1970s free-flowing technique. Zsigmond won a National Society of Film Critics Award for his work on this film.

Music-wise, The Long Goodbye is very eccentric. It opens and closes with the old Richard A. Whiting song "Hooray for Hollywood" - and you could probably go mad trying to figure out why, which is possibly (considering Altman) the reason it's there. The rest of the film either features or is scored with the same song, played over and over again in differing styles, with different instruments and/or with different singers. Written by John Williams and Johnny Mercer, "The Long Goodbye" is a jazz-like slow number that fits the noir style of the film, although at different times it morphs into whatever situation it's needed in. You'll hear the same song and tune over and over again - and it's something that's pushed to the forefront of the film. It's an attention-getting method of creating the musical accompaniment to the film, and very Robert Altman-like in it's experimental nature and in the way it absolutely fits. It almost feels as if the changes in tune relate to the changes in society, mood, character and meaning we see in the film. The same song, but a different tune - it's an actual saying which takes on a literal form here, and it's hard to escape the conclusion that this is very deliberate.

Lou Lombardo, editor of Brewster McCloud and McCabe & Mrs. Miller returned to edit this film, doing excellent work yet again. Tommy Thompson, who had been assistant director on Brewster McCloud and McCabe and Mrs. Miller along with being a producer on Images was assistant again and would work with Altman on countless other films. Acting-wise, there wasn't any return of the Altman ensemble we'd see in so many films, though of course Elliott Gould had featured in M*A*S*H, as had David Arkin, who plays Augustine underling Harry. Stephen Coit, who plays a police detective, featured in Altman film Countdown, and Jack Riley, who has a very small role, was in McCabe & Mrs. Miller. All in all, the film wasn't a big hit when it was released, but caught on like a cinematic snowball over the years as it accumulated more and more fans - until it became the much talked about staple of film lovers today - often reissued and broadcast, shown again at theaters and becoming a classic. Pauline Kael gave it a long, positive review in The New Yorker, and Roger Ebert praised it. Gene Siskel gave it three and a half out of four stars - calling it "a most satisfying motion picture" - but box office success wasn't in the offing, for The Long Goodbye was still far from being mainstream entertainment.

The Long Goodbye is packed with little pieces of trivia, and has an assortment of surprise guest performers on it's margins. David Carradine turns up in a jail cell, espousing hippie wisdom in a casual, measured fashion - a delightful surprise for those unprepared. Arnold Schwarzenegger is an even bigger surprise, appearing nearly a decade before his breakout starring roles in Conan the Barbarian and The Terminator - he has no lines, but draws all of our attention as a heavy in Augustine's office, at one point undressing to his underwear. Elliott Gould glances at him and laughs - and that probably wasn't in the screenplay, for as per usual the cast were encouraged to ad-lib and many of the scenes were improvised in this way. It was the way Altman liked to work, and it gave him naturalistic results. The film overflows with extra touches - Zsigmond captures a lot of action in reflections, sometimes showing us two images at once, and he sometimes shoots through things, distorting and interrupting the flow of what we can see. All of this is what makes Altman films so enjoyable to watch - and he's at his peak working on The Long Goodbye.

This film can't be fully encapsulated in one review. It's one of a thousand little touches, half a dozen great performances (including a couple from a baseball player and film director) and an Altman/Zsigmond peak of visual acuity. It's less a neo-noir as it is a film about the neo-noir genre and Marlowe character. However, it's more than that, and it's always misleading to pin one label on The Long Goodbye. The film's beginning features a protracted lesson to us on how loyal Marlowe is to his cat, and a frivolous illustration of a funny story Altman heard about a friend trying to mislead his fussy feline by switching cat food and cans - so you never know where it might lead. Instead of a mystery that starts out muddied and becomes clear - everything starts out perfectly clear and by the end of the film we have a million questions. It's not only endlessly rewatchable, but improves on every subsequent watch as you notice more and more detail you missed the first, second and third time around. What more could you ask for from a film? Any more doesn't seem possible. What seems on the surface perfectly suited to it's genre, is something that's anarchic, rebellious and of a piece with Altman's other films. It's Altman's noir - there's never been anything like it, and there never will be again.

The Long Goodbye - 1973

Directed by Robert Altman

Written by Leigh Brackett

Based on the novel "The Long Goodbye" by Raymond Chandler

Starring Elliott Gould, Nina van Pallandt, Sterling Hayden, Mark Rydell

Henry Gibson & Jim Bouton

The longer you look at The Long Goodbye the more remarkable it seems, and the better sense you get of what you should be focusing on. In a neo-noir film based on a 1953 Raymond Chandler novel you'd think it would be the mystery - but this is more Robert Altman movie than Raymond Chandler story - character, atmosphere and a heady blend of themes create a work of art far from your typical noir story. Elliott Gould's Philip Marlowe becomes a private investigator from the 1950s trapped in the 1970s - and many questions remain ambiguously unanswered. Chandler's Long Goodbye has been infected by a different time, with different moralities. The ever-smoking, wisecrack-master washes through a world where topless, acid-dropping yoga enthusiasts work out opposite his apartment, hoodlums scar their lovers to make a point and truth becomes harder and harder to grasp. It's a world so changed that Marlowe has become a kind of child-like, innocent spectator - loyal to his friends and pets to the last, at a time when loyalty has gone extinct.

During a sleepless night, after trying to please his fussy cat, Philip Marlowe is visited by his only friend, Terry Lennox (Jim Bouton) who is sporting some impressive wounds on his cheek. Lennox speaks of having had a massive fight with his wife, and asks to be driven to Tijuana. The next day the police come looking for Marlowe - it seems that Terry has actually murdered his wife, and until Marlowe gives the cops information they'll hold him as an accessory. When Terry's body is found in an apparent suicide, they let Marlowe go - but the private investigator is sure that Terry is innocent - he knows him too well. In the meantime, he gets a job offer from an Eileen Wade (Nina van Pallandt) whose husband, Roger (Sterling Hayden) has gone on another bender and is missing. Marlowe tracks down a Dr. Verringer (Henry Gibson) who is trying to extort money from Roger, and brings him home. He's also visited by gangster Marty Augustine (Mark Rydell) who threatens to kill Marlowe unless he recovers the $350,000 that Terry took with him the night he went to Tijuana. When Roger commits suicide, and Marlowe finds out that he may have killed Terry Lennox's wife, he begins to suspect that Terry's suicide is not what it seems, and heads to Tijuana to chase down the truth.

Many questions remain unanswered, even after the big, dramatic reveal at the end of the film. Screenwriter Leigh Brackett really made the story her own - she'd previously written the screenplay for The Big Sleep, which featured Humphrey Bogart as Marlowe, and her surprise ending along with other quirks caught Altman's eye and imagination. He made sure that he wouldn't be forced to change these aspects of her screenplay, and this is how we got the Long Goodbye we have - a film which simply grows and grows in stature as the decades pass. On it's initial screenings, touted as being a straight noir/mystery/detective story, audiences were mystified and upset - it was then that the studio executives and distributors realised they had something different on their hands. It wasn't straightforward. That's the crux of this movie - you can't approach it like that, because the heart and soul of the film is in what it captures thematically onscreen. The loyal and bewildered Marlowe, the world he inhabits and the characters that contribute to the concoction of a strange Los Angeles society where morals and mores have shifted. For this, Elliott Gould gives what is perhaps the greatest performance of his career - for good reason, for his career was nearly over and he needed this.

Behind the lens, once again, Altman had cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond doing the director of photography work. Zsigmond had been with Altman on McCabe & Mrs. Miller and Images - Altman once again taking advantage of Zsigmond's proclivity to "flash" the negatives he'd use - exposing them to sunlight so they'd fade a little and turn bright colours into more subdued pastels, darkening the image. It creates the kind of atmosphere that seems to send 1970s L.A. back into the 40s and 50s in visual feel. He also demanded that the camera never rest or be static - it doesn't mean that we're careening all over the place or constantly in motion, but you'll notice that we're never completely still, and even static shots have a little bit of sway and movement to them - along with a little zoom, which shows up often. It does give the impression of being inside the picture. There's also a lot of reflectino and obfuscation. Altman has his own, recognizable visual style by this point in his filmmaking career, and The Long Goodbye is very much a part of his 1970s free-flowing technique. Zsigmond won a National Society of Film Critics Award for his work on this film.

Music-wise, The Long Goodbye is very eccentric. It opens and closes with the old Richard A. Whiting song "Hooray for Hollywood" - and you could probably go mad trying to figure out why, which is possibly (considering Altman) the reason it's there. The rest of the film either features or is scored with the same song, played over and over again in differing styles, with different instruments and/or with different singers. Written by John Williams and Johnny Mercer, "The Long Goodbye" is a jazz-like slow number that fits the noir style of the film, although at different times it morphs into whatever situation it's needed in. You'll hear the same song and tune over and over again - and it's something that's pushed to the forefront of the film. It's an attention-getting method of creating the musical accompaniment to the film, and very Robert Altman-like in it's experimental nature and in the way it absolutely fits. It almost feels as if the changes in tune relate to the changes in society, mood, character and meaning we see in the film. The same song, but a different tune - it's an actual saying which takes on a literal form here, and it's hard to escape the conclusion that this is very deliberate.

Lou Lombardo, editor of Brewster McCloud and McCabe & Mrs. Miller returned to edit this film, doing excellent work yet again. Tommy Thompson, who had been assistant director on Brewster McCloud and McCabe and Mrs. Miller along with being a producer on Images was assistant again and would work with Altman on countless other films. Acting-wise, there wasn't any return of the Altman ensemble we'd see in so many films, though of course Elliott Gould had featured in M*A*S*H, as had David Arkin, who plays Augustine underling Harry. Stephen Coit, who plays a police detective, featured in Altman film Countdown, and Jack Riley, who has a very small role, was in McCabe & Mrs. Miller. All in all, the film wasn't a big hit when it was released, but caught on like a cinematic snowball over the years as it accumulated more and more fans - until it became the much talked about staple of film lovers today - often reissued and broadcast, shown again at theaters and becoming a classic. Pauline Kael gave it a long, positive review in The New Yorker, and Roger Ebert praised it. Gene Siskel gave it three and a half out of four stars - calling it "a most satisfying motion picture" - but box office success wasn't in the offing, for The Long Goodbye was still far from being mainstream entertainment.

The Long Goodbye is packed with little pieces of trivia, and has an assortment of surprise guest performers on it's margins. David Carradine turns up in a jail cell, espousing hippie wisdom in a casual, measured fashion - a delightful surprise for those unprepared. Arnold Schwarzenegger is an even bigger surprise, appearing nearly a decade before his breakout starring roles in Conan the Barbarian and The Terminator - he has no lines, but draws all of our attention as a heavy in Augustine's office, at one point undressing to his underwear. Elliott Gould glances at him and laughs - and that probably wasn't in the screenplay, for as per usual the cast were encouraged to ad-lib and many of the scenes were improvised in this way. It was the way Altman liked to work, and it gave him naturalistic results. The film overflows with extra touches - Zsigmond captures a lot of action in reflections, sometimes showing us two images at once, and he sometimes shoots through things, distorting and interrupting the flow of what we can see. All of this is what makes Altman films so enjoyable to watch - and he's at his peak working on The Long Goodbye.

This film can't be fully encapsulated in one review. It's one of a thousand little touches, half a dozen great performances (including a couple from a baseball player and film director) and an Altman/Zsigmond peak of visual acuity. It's less a neo-noir as it is a film about the neo-noir genre and Marlowe character. However, it's more than that, and it's always misleading to pin one label on The Long Goodbye. The film's beginning features a protracted lesson to us on how loyal Marlowe is to his cat, and a frivolous illustration of a funny story Altman heard about a friend trying to mislead his fussy feline by switching cat food and cans - so you never know where it might lead. Instead of a mystery that starts out muddied and becomes clear - everything starts out perfectly clear and by the end of the film we have a million questions. It's not only endlessly rewatchable, but improves on every subsequent watch as you notice more and more detail you missed the first, second and third time around. What more could you ask for from a film? Any more doesn't seem possible. What seems on the surface perfectly suited to it's genre, is something that's anarchic, rebellious and of a piece with Altman's other films. It's Altman's noir - there's never been anything like it, and there never will be again.