I originally intended this as a reply to Movie Tab II, but I decided that I could open up a new thread, so that is why this is presented as a "movie review". I intend to get into Night and Fog next, and then try to get ahold of all those Resnais films I saw once 30 years ago. Please feel free to add anything you know about the man and his films.

Hiroshima Mon Amour (Alain Resnais, 1959)

Back in 1976, when I was getting my Biology degree from the University of California at Irvine, this barely-20-year-old punk junior had the revelation that he would rather study movies than become a doctor, so I eventually took 11 classes in film (the equivalent of one full year of college), and none was more esoteric (at least at the time) than the Cinema of Alain Resnais. Week after week, I watched films (on 16mm film - no VCRs at the time) which were beautifully shot and edited, but which seemed to be so highly personal that I had an extremely difficult time trying to penetrate what I thought to be their meanings. However, the fact that UCI could actually get their hands on all those films proved to me that I was getting a pretty good education in world cinema. To this day, this is the only Resnais film which I've seen more than once, with the exception of one of my Criterion pride and joys, Night and Fog. Now that I've seen it three times and am over 50, I feel that I'm mature enough to discuss it intelligently.

Before I get into the film proper, I want to mention that from interviews, Alain Resnais doesn't believe himself to be an auteur, and in fact, he mostly seems to debunk the idea of the theory itself (unless he's lying). He goes out of his way to credit all his co-creators of his films, especially the screenwriters. He also believes himself to be, first and foremost, an editor, and he calls editing a "trade" and not an art. Well, back 30 years ago, I would never have believed that because his films all carried a highly personal stamp, mostly in theme, cinematography and escalating editing techniques, but maybe Resnais is correct in the fact that he's responsible for his films but he goes out of his way to surround himself with people who are on the same wavelength. I realize that this is just common sense, but here I was today, watching Resnais say that he is not an auteur, and yet he seems to be just about the most idiosyncratic filmmaker I've experienced.

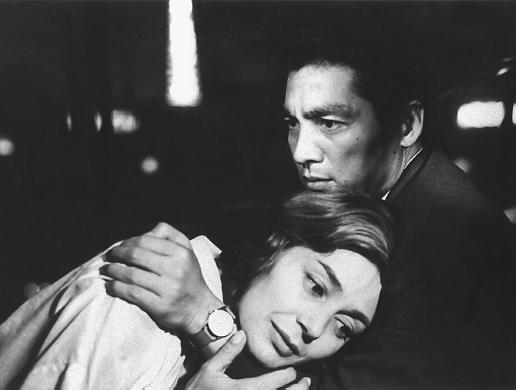

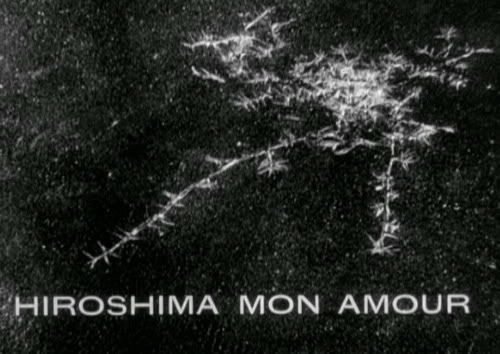

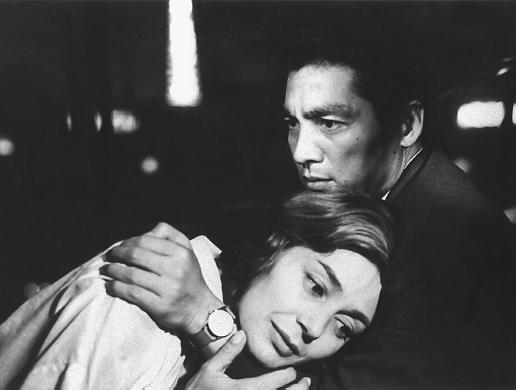

The film begins with some lowkey, yet somewhat upsetting, music playing over a credit which has the background of the opening shot above. When the credits end, we see what appears to be a quiet naked couple holding onto each other for dear life, but there bodies are covered by something resembling ash which is falling from above. Before we ever see their faces, the couple, speaking in French, seem to almost chant about how they met in Hiroshima, what they know about the A-Bomb which was dropped 14 years earlier, and how the male just never believes what the female says. We come to learn that the female is a French actress (Emmanuelle Riva) who is in Hiroshima finishing up her part in a "Peace Film" and that the male is a Japanese architect-politician (Eiji Okada). They are both married to others, but they have found with each other an intimacy which they have never had with their spouses. We eventually learn why the woman relates so strongly to her experiences in Hiroshima, although the man remains a bit more of an enigma (although Emmanuelle Riva is an incredibly attractive and responsive human being whom everyone should find worth their time).

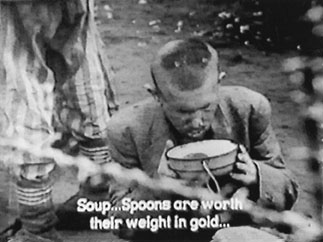

Unfortunately, I cannot find many of the most stunning visual scenes in the film. However, these should give you a notion of how intensely romantic and sexual they are. The film could not be rated more than a PG in our current system, but the maturity level of the actual exchanges between the couple basically requires an adult "education" and probably a rough one at that. Without giving away too much, I would subtitle this film (and almost all of Resnais' work) as War and Rememberance. Apparently, scripter Marguerite Duras came up with most of the specific ideas which enabled Resnais to adapt a documentary he was shooting about Hiroshima (along the lines of the Auschwitz-set Night and Fog) into a narrative feature about two people, traumatized by WWII, who meet and completely let themselves go with each other, yet they also become embroiled with the passion and true concern that brings back all the memories of the past.

Ultimately, Hiroshima Mon Amour is a film full of images and emotion. I have no problem at all if someone wanted to call it a masterpiece because in my world, it should be seen and reseen. It's much more inviting than many of Resnais' later "picture puzzles" with similar themes. However, I find the need to warn people who aren't all that familiar with 50-year-old European cinema that, at times, they may be confused or bored by it, just as I was 30+ years ago. My rating is still an honest rating for me, but I do have a love for this film which seems to grow a bit with each word I type. Just thinking about the low-angle tracking shot when the Woman walks down a brightly-lit Hiroshima street at night is making me smile. Yet, on the other hand, although most of what's in the film is truly affecting, it still seems overlong at 90 minutes, and I don't believe they ever came up with a proper ending, although it certainly is a poetic one.

P.S. Sarah told me that the first thing she thought of while watching Hiroshima Mon Amour is that it reminded her of Brief Encounter. I hugged her and told her I thought that was great! Then, I asked her to dig deeper

Hiroshima Mon Amour (Alain Resnais, 1959)

Back in 1976, when I was getting my Biology degree from the University of California at Irvine, this barely-20-year-old punk junior had the revelation that he would rather study movies than become a doctor, so I eventually took 11 classes in film (the equivalent of one full year of college), and none was more esoteric (at least at the time) than the Cinema of Alain Resnais. Week after week, I watched films (on 16mm film - no VCRs at the time) which were beautifully shot and edited, but which seemed to be so highly personal that I had an extremely difficult time trying to penetrate what I thought to be their meanings. However, the fact that UCI could actually get their hands on all those films proved to me that I was getting a pretty good education in world cinema. To this day, this is the only Resnais film which I've seen more than once, with the exception of one of my Criterion pride and joys, Night and Fog. Now that I've seen it three times and am over 50, I feel that I'm mature enough to discuss it intelligently.

Before I get into the film proper, I want to mention that from interviews, Alain Resnais doesn't believe himself to be an auteur, and in fact, he mostly seems to debunk the idea of the theory itself (unless he's lying). He goes out of his way to credit all his co-creators of his films, especially the screenwriters. He also believes himself to be, first and foremost, an editor, and he calls editing a "trade" and not an art. Well, back 30 years ago, I would never have believed that because his films all carried a highly personal stamp, mostly in theme, cinematography and escalating editing techniques, but maybe Resnais is correct in the fact that he's responsible for his films but he goes out of his way to surround himself with people who are on the same wavelength. I realize that this is just common sense, but here I was today, watching Resnais say that he is not an auteur, and yet he seems to be just about the most idiosyncratic filmmaker I've experienced.

The film begins with some lowkey, yet somewhat upsetting, music playing over a credit which has the background of the opening shot above. When the credits end, we see what appears to be a quiet naked couple holding onto each other for dear life, but there bodies are covered by something resembling ash which is falling from above. Before we ever see their faces, the couple, speaking in French, seem to almost chant about how they met in Hiroshima, what they know about the A-Bomb which was dropped 14 years earlier, and how the male just never believes what the female says. We come to learn that the female is a French actress (Emmanuelle Riva) who is in Hiroshima finishing up her part in a "Peace Film" and that the male is a Japanese architect-politician (Eiji Okada). They are both married to others, but they have found with each other an intimacy which they have never had with their spouses. We eventually learn why the woman relates so strongly to her experiences in Hiroshima, although the man remains a bit more of an enigma (although Emmanuelle Riva is an incredibly attractive and responsive human being whom everyone should find worth their time).

Unfortunately, I cannot find many of the most stunning visual scenes in the film. However, these should give you a notion of how intensely romantic and sexual they are. The film could not be rated more than a PG in our current system, but the maturity level of the actual exchanges between the couple basically requires an adult "education" and probably a rough one at that. Without giving away too much, I would subtitle this film (and almost all of Resnais' work) as War and Rememberance. Apparently, scripter Marguerite Duras came up with most of the specific ideas which enabled Resnais to adapt a documentary he was shooting about Hiroshima (along the lines of the Auschwitz-set Night and Fog) into a narrative feature about two people, traumatized by WWII, who meet and completely let themselves go with each other, yet they also become embroiled with the passion and true concern that brings back all the memories of the past.

Ultimately, Hiroshima Mon Amour is a film full of images and emotion. I have no problem at all if someone wanted to call it a masterpiece because in my world, it should be seen and reseen. It's much more inviting than many of Resnais' later "picture puzzles" with similar themes. However, I find the need to warn people who aren't all that familiar with 50-year-old European cinema that, at times, they may be confused or bored by it, just as I was 30+ years ago. My rating is still an honest rating for me, but I do have a love for this film which seems to grow a bit with each word I type. Just thinking about the low-angle tracking shot when the Woman walks down a brightly-lit Hiroshima street at night is making me smile. Yet, on the other hand, although most of what's in the film is truly affecting, it still seems overlong at 90 minutes, and I don't believe they ever came up with a proper ending, although it certainly is a poetic one.

P.S. Sarah told me that the first thing she thought of while watching Hiroshima Mon Amour is that it reminded her of Brief Encounter. I hugged her and told her I thought that was great! Then, I asked her to dig deeper

__________________

It's what you learn after you know it all that counts. - John Wooden

My IMDb page

It's what you learn after you know it all that counts. - John Wooden

My IMDb page

Last edited by Yoda; 07-17-14 at 11:43 AM.

)

)