← Back to Reviews

in

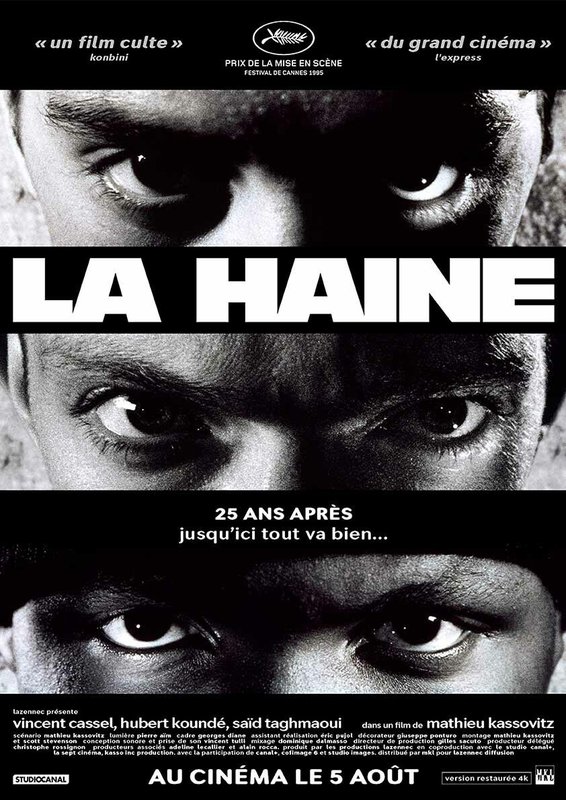

La Haine - 1995

Directed by Mathieu Kassovitz

Written by Mathieu Kassovitz

Starring Vincent Cassel, Hubert Koundé & Saïd Taghmaoui

When I think of La Haine, I think of the concrete wasteland and how Pierre Aïm's black & white photography turns everything into different shades of cement. Paris looks like one gigantic prison - for the kids who grow up there, nothing much pleases the eye. Everywhere graffiti speaks for the kids who live there in protest. There are damp tunnels, endless tenements and at the moment this film takes place uniformed police around every corner - who wouldn't want to break free? Who wouldn't resent this after a while - when your socioeconomic status means the kids who you hang out with help push drugs, and deal in stolen goods. When every so often you get picked up by the wrong cops, and are brutalized because you've been lumped with punks and hoodlums. For me the black & white of La Haine really emphasizes the concrete desolation of the poorer areas of Paris, where the unemployed and underemployed eke out a living, their kids running wild in a world where there's nothing to do but get into trouble.

The film itself deals with a day in the life of three kids : Vinz (Vincent Cassel), from a Jewish family but not devout, Hubert (Hubert Koundé), who likes boxing and trains in a gym which has just been destroyed in the latest riots, and Saïd (Saïd Taghmaoui), a North African Muslim who is the glue who keeps the three together. They are friends in the sense kids generally are when they hang out together each day. During that last riot a cop lost his gun, and it was Vinz who found it. He declares that he's going to get revenge for the latest injustice done to a kid by the cops - Abdel Ichaha (Abdel Ahmed Ghili) was brutalized by the police and is in critical condition. Hubert doesn't want Vinz to throw his life away by killing a cop - and is angry at him for having those intentions. The three of them travel around in an almost aimless fashion, trying to visit Abdel in hospital, and travelling into central Paris causing trouble and having fun. Guns though, have a tendency to cause grief all by themselves - they just need fools to carry them.

It's no easy equation. I mean, there are good cops, and there are bad cops. Then there are good kids and bad kids. Do you blame the bad kids when everything goes to hell? Whose fault is it that their lives are ones of misery, crime and waste? You can certainly blame one if he sets your car on fire - but the bigger picture has the blame on those who would keep their feet on the necks of the poor, making sure economic disparity keeps money flowing upwards. In the meantime, some cops start out in an idealistic manner, until a friend gets killed or a kid hurts them - after a while they can turn. In any case, much exists in that grey area where there are no easy answers - and I think you'd find most kids are good. The really bad ones lead from the front - do the burning, and the hurting. In the midst of the fighting and the shouting - the scuffles and the arrests - the burning and the looting - a shot rings out, and down goes one of these kids. One of the ones who weren't all that bad really. Down they go - they fall to the concrete ground dying. The cop whose gun has gone off is sometimes good and sometimes bad. It's the situation that leads to this inevitable result - again and again.

La Haine has us hang out with three kids who are no angels, but are no evil psychopaths either. They're no racists, but they deal drugs and smoke dope. They are where they are in their lives almost literally because they are where they are. They live in the Paris slums. This is simply what it is like - they're products of their community, and they're products of their status. Nobody helps Hubert get somewhere boxing - he's the one who has to help his family financially, not the other way around. They don't know anything at all of what exists outside of their small world of petty crime, selling dope, shoplifting, and roaming the streets looking for something to do. They're just following in the footsteps of all the kids who went before them - and even if they really wanted a job, there's no good prospects from where they stand. They'd have to fight tooth and nail for the lowliest, dirty jobs available - and with easier ways of earning money, kids like these have their paths already marked out. There's nothing for them - and at that age boredom is something not to be tolerated.

The feeling we get from La Haine is a very energetic one - the camera moves in an almost documentary fashion, and we scurry around a lot with the kids. The soundtrack leads with Burnin' and Lootin' by Bob Marley, but it's when DJ Cut Killer gives us an onscreen diegetic mix of Edith Piaf and KRS One that the film really gives you a full-on impression of how it's using rap and reggae to produce an authentic "French dissent" sound to the film. It's a sound that infuses itself into the film and is inseparable from the visual aspect. It's the sound of controlled anger - it's a taunt and a protest aimed at the most visual manifestation of these kids' pain, and that's the police themselves. Most of the graffiti that the action nearly centers itself around alludes to the cops. It's a terrific sound though - the soundtrack driven mixture is at the forefront and really drives the point home. Really a huge part of this film - and helps to draw positives from the youth culture here, such as when our three protagonists stop to watch some talented dancers perform well-rehearsed routines that are genuinely incredible.

I also like the little moments in La Haine that speak to the issues on a large or small scale. The kids visit a guy who's car has been burned to a husk - to them it's nothing, and to us on a large scale, it's just protest. But to the guy who's car has been destroyed, it's their entire life upended, wrecked and ruined because cars are expensive and often the lack of one has a debilitating effect on how a person gets by in the world. These kids are burning cars that belong to average Joes - sometimes people in economic circumstances not that different to them. It's part of the protest that's senseless, because the target is so random. Because of where these kids live, they end up burning the infrastructure around them. Hubert's gym has been completely destroyed in the riots - what was the purpose of that, if the riots themselves were in response to the harm being done to the kids in the area? When the kids strike out - it's often blindly, and never calculated and thus, often it makes little sense.

So, obviously a powerful film - especially with the ending it has, which is the whole point rammed home. It doesn't pontificate - it does what all good movies do, which is it simply shows. We get a sense of who these kids are, and in the main they're simply kids. It has a living pulse, and although the kids are often blind to it, we see the good cops and the bad cops around. We see the fear, and we see the hate. We see that the enemy really is the hate - and like germs, the hate breeds in all corners of the Paris slums. It festers, and it becomes inflamed by every accident - every inevitable accident brought about by the conditions around these kids. It becomes inflamed whenever an act of hatred is given the ultimate outlet, as we see in the film. But as long as there are slums, the hate will still be there. You can't have one without the other. You almost feel that there's need of another revolution - because without one the money will never stop flowing to those who don't need more of it, and it will never go to those who desperately need it. I'm not talking socialism - I'm just talking common decency, and common sense.

La Haine - 1995

Directed by Mathieu Kassovitz

Written by Mathieu Kassovitz

Starring Vincent Cassel, Hubert Koundé & Saïd Taghmaoui

When I think of La Haine, I think of the concrete wasteland and how Pierre Aïm's black & white photography turns everything into different shades of cement. Paris looks like one gigantic prison - for the kids who grow up there, nothing much pleases the eye. Everywhere graffiti speaks for the kids who live there in protest. There are damp tunnels, endless tenements and at the moment this film takes place uniformed police around every corner - who wouldn't want to break free? Who wouldn't resent this after a while - when your socioeconomic status means the kids who you hang out with help push drugs, and deal in stolen goods. When every so often you get picked up by the wrong cops, and are brutalized because you've been lumped with punks and hoodlums. For me the black & white of La Haine really emphasizes the concrete desolation of the poorer areas of Paris, where the unemployed and underemployed eke out a living, their kids running wild in a world where there's nothing to do but get into trouble.

The film itself deals with a day in the life of three kids : Vinz (Vincent Cassel), from a Jewish family but not devout, Hubert (Hubert Koundé), who likes boxing and trains in a gym which has just been destroyed in the latest riots, and Saïd (Saïd Taghmaoui), a North African Muslim who is the glue who keeps the three together. They are friends in the sense kids generally are when they hang out together each day. During that last riot a cop lost his gun, and it was Vinz who found it. He declares that he's going to get revenge for the latest injustice done to a kid by the cops - Abdel Ichaha (Abdel Ahmed Ghili) was brutalized by the police and is in critical condition. Hubert doesn't want Vinz to throw his life away by killing a cop - and is angry at him for having those intentions. The three of them travel around in an almost aimless fashion, trying to visit Abdel in hospital, and travelling into central Paris causing trouble and having fun. Guns though, have a tendency to cause grief all by themselves - they just need fools to carry them.

It's no easy equation. I mean, there are good cops, and there are bad cops. Then there are good kids and bad kids. Do you blame the bad kids when everything goes to hell? Whose fault is it that their lives are ones of misery, crime and waste? You can certainly blame one if he sets your car on fire - but the bigger picture has the blame on those who would keep their feet on the necks of the poor, making sure economic disparity keeps money flowing upwards. In the meantime, some cops start out in an idealistic manner, until a friend gets killed or a kid hurts them - after a while they can turn. In any case, much exists in that grey area where there are no easy answers - and I think you'd find most kids are good. The really bad ones lead from the front - do the burning, and the hurting. In the midst of the fighting and the shouting - the scuffles and the arrests - the burning and the looting - a shot rings out, and down goes one of these kids. One of the ones who weren't all that bad really. Down they go - they fall to the concrete ground dying. The cop whose gun has gone off is sometimes good and sometimes bad. It's the situation that leads to this inevitable result - again and again.

La Haine has us hang out with three kids who are no angels, but are no evil psychopaths either. They're no racists, but they deal drugs and smoke dope. They are where they are in their lives almost literally because they are where they are. They live in the Paris slums. This is simply what it is like - they're products of their community, and they're products of their status. Nobody helps Hubert get somewhere boxing - he's the one who has to help his family financially, not the other way around. They don't know anything at all of what exists outside of their small world of petty crime, selling dope, shoplifting, and roaming the streets looking for something to do. They're just following in the footsteps of all the kids who went before them - and even if they really wanted a job, there's no good prospects from where they stand. They'd have to fight tooth and nail for the lowliest, dirty jobs available - and with easier ways of earning money, kids like these have their paths already marked out. There's nothing for them - and at that age boredom is something not to be tolerated.

The feeling we get from La Haine is a very energetic one - the camera moves in an almost documentary fashion, and we scurry around a lot with the kids. The soundtrack leads with Burnin' and Lootin' by Bob Marley, but it's when DJ Cut Killer gives us an onscreen diegetic mix of Edith Piaf and KRS One that the film really gives you a full-on impression of how it's using rap and reggae to produce an authentic "French dissent" sound to the film. It's a sound that infuses itself into the film and is inseparable from the visual aspect. It's the sound of controlled anger - it's a taunt and a protest aimed at the most visual manifestation of these kids' pain, and that's the police themselves. Most of the graffiti that the action nearly centers itself around alludes to the cops. It's a terrific sound though - the soundtrack driven mixture is at the forefront and really drives the point home. Really a huge part of this film - and helps to draw positives from the youth culture here, such as when our three protagonists stop to watch some talented dancers perform well-rehearsed routines that are genuinely incredible.

I also like the little moments in La Haine that speak to the issues on a large or small scale. The kids visit a guy who's car has been burned to a husk - to them it's nothing, and to us on a large scale, it's just protest. But to the guy who's car has been destroyed, it's their entire life upended, wrecked and ruined because cars are expensive and often the lack of one has a debilitating effect on how a person gets by in the world. These kids are burning cars that belong to average Joes - sometimes people in economic circumstances not that different to them. It's part of the protest that's senseless, because the target is so random. Because of where these kids live, they end up burning the infrastructure around them. Hubert's gym has been completely destroyed in the riots - what was the purpose of that, if the riots themselves were in response to the harm being done to the kids in the area? When the kids strike out - it's often blindly, and never calculated and thus, often it makes little sense.

So, obviously a powerful film - especially with the ending it has, which is the whole point rammed home. It doesn't pontificate - it does what all good movies do, which is it simply shows. We get a sense of who these kids are, and in the main they're simply kids. It has a living pulse, and although the kids are often blind to it, we see the good cops and the bad cops around. We see the fear, and we see the hate. We see that the enemy really is the hate - and like germs, the hate breeds in all corners of the Paris slums. It festers, and it becomes inflamed by every accident - every inevitable accident brought about by the conditions around these kids. It becomes inflamed whenever an act of hatred is given the ultimate outlet, as we see in the film. But as long as there are slums, the hate will still be there. You can't have one without the other. You almost feel that there's need of another revolution - because without one the money will never stop flowing to those who don't need more of it, and it will never go to those who desperately need it. I'm not talking socialism - I'm just talking common decency, and common sense.