← Back to Reviews

in

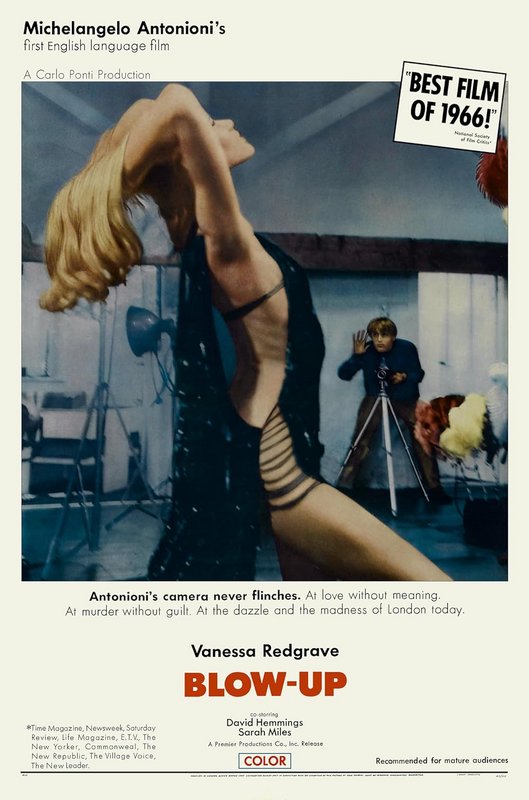

Blow-Up - 1966

Directed by Michelangelo Antonioni

Written by Michelangelo Antonioni & Tonino Guerra

Based on a short story by Julio Cortázar

Starring David Hemmings, Vanessa Redgrave & Sarah Miles

I have a pet theory about auteur films that have great interpretive scope. I believe a filmmaker and screenwriter can make one without knowing which interpretation they're aiming for - and further, that the less the person making the film knows what it's about, the better the film. It takes a person's subconscious to weave a good dream-rug made from metaphor, overtone, parable and connotation. We've all seen the opposite - clunky, awkward movies that are heavy-handed and leave little room for analysis. Films full of dead-certain giveaways. Blow-Up, Michelangelo Antonioni's surprisingly popular first English language film, has been debated and commented upon ever since it was released, over 50 years ago. There's no definitive word on what it's about - exactly. It speaks to us in the same way dreams speak to us, and as such it's an enjoyable sport to interpret and analyse. Most of what I have to say about the film is my own personal take-away from it, and is not meant as a definite and definitive guide, obviously.

In Blow-Up we have central character Thomas, a high-end, high-priced photographer that works taking pictures that appear everywhere in the cultural epoch of 1960s London. He drives a Rolls Royce, and lives a life of debauched freedom - taking photographs that speak about a reality that he sees, and tries to experience. One day, he takes pictures of a young woman and older man frolicking in the park - and the woman proceeds to beg him to either destroy the negative or hand it over to her. Thomas, piqued by the possible value his pictures have, and the power they give him over the woman in question, keeps them. When he develops the photos, he notices a shape in the bushes off to the right, and as he blows it up larger, and larger, he can see the shape of a man who appears to be holding a gun. Later, one of the last photographs he had taken is also enlarged - and shows the man in the park collapsed onto the ground. He goes to the park to investigate, and finds the dead body, but before he can formulate any kind of action his pictures, negatives and the body slip through his fingers. With no evidence - how can Thomas ever prove it really happened?

Everything that happens, and every line of dialogue, is very suggestive in Blow-Up - not a moment is wasted not conveying some kind of important meaning and as such you're never left to just tread water. When I watch it I'm constantly thinking, "...and what did that mean?" When the film makes a point of going on a detour, you know it isn't just wasting our time. Most interesting to me is when, early in the film, Thomas talks to a painter who, in explaining his work, says “They don't mean anything when I do them. Afterwards, I find something to hang onto. Like that leg,” and he points to a leg that can only just be made out in a very surreal image. This seems to not only be a statement about the film and reality, but also directly illuminates what Thomas is doing when he's blowing up his photographs. Hell, it's how I interpret the movie as well - finding something to hang onto so I can start formulating some kind of larger purpose. That's what I'll do here, I'll take the obvious instances of explicit meaning and see if I can tie it all together. Aside from the more outwardly real aspects, such as how much Thomas enjoys the power he has over people looking for fame, fortune or the need to hide what he captures with his camera - a device that never lies - or does it?

First up, I'll take what comes last in the film. There's a significant and lengthy scene to finish it off which features Thomas watching a group of mimes playing a kind of "mime tennis", pretending there's a ball. At one stage the mimes pretend the ball has gone over the fenced enclosure, and ask Thomas to continue the performance by running after the invisible ball, and "returning" it - which he does, now fully invested in the performance himself. All of this is obviously alluding to the nature of shared reality, and also the sharing of a reality that's not objectively real. Now, we go back to the beginning of the film - Thomas was dressed up in dirty bum-clothes, pretending to be a penniless wino living in a doss house. Why? So he could mingle and take naturalistic photographs of what goes on in there. We have that duality of realities there as well. While Thomas is in there, in dirty clothes, he's indistinguishable from any other person in there. You could well say he's one of them at that moment - but objectively he's not. He's a rich photographer. So, those things must be important to the film. Shared reality, objective reality and the interesting question posed - does a shared belief constitute some kind of reality, even if it's not objectively real?

The models Thomas takes photographs of are also a good illustration of that fine line. They don't own the expensive clothes they're wearing, and their expressions do not convey what they're thinking. When you look at them in magazines, they look real - but very little of what you're seeing is. In fact, only the physical image. So, an interpretation of a photograph cannot be considered objective reality without some kind of confirmation. What about art? What's real there? What constitutes reality? Reality is what the artist friend of Thomas begins with - "That's a leg." It's what you recognize. A gun. A leg. A person. A tree. Now, look at what happens to Thomas and his park photographs. The first thing we all recognize is a man and a woman. Lovers. Play. Sex. An affair perhaps? They're alone. But when Thomas looks closer it all breaks down. He finds something else to "hang onto" - a man with a gun. It changes the reality completely. Like Thomas in the doss house, this was just dressed up - a pretend fling for the woman. The reality is now a conspiracy. For Thomas, reality has changed - he looked closer.

If reality itself can change for Thomas when he looks closer, what does that say for all of us? Just look at Sir Isaac Newton, who had seemingly unlocked the secret of gravity. From that moment on, the reality for everyone science-minded had been defined. Then Albert Einstein looked closer, much like Thomas does. Then reality - for everyone - changed. If that can happen, how can we ever think of reality as anything other than something impermanent? Elusive? We hunger for something eternal - something that's some kind of bedrock. Turns out reality - whatever it is for us - is a shifting phenomenon. We can reach out and grasp onto things - "That's a leg" and "That's a dog," but when we cast our eyes around, constantly and insistently defining our reality, our mind often tricks us into the comfort of thinking that we're on top of it. Look at what the girl says in that famous quote towards the end. "I am in Paris" - it perfectly illustrates all of this. Her reality is different - like in 1984, where O'Brien says "The Law of Gravity is nonsense. No such law exists. If I think I float, and you think I float, then it happens." Does objective reality even exist, if it's not being percieved? Is there such a thing?

So, there's one important part of Blow-Up that I've been trying to add to this meaning. Throughout the film, there are constant instances of distraction. Distraction is a huge part of the puzzle. When the mysterious woman is with Thomas, he's distracted by the arrival of the propeller he bought. When he's figuring out his blown-up photograph, the two girls arrive and distract him from examining them further, and acting on the information. When he sees the mysterious woman again, he chases her through London, and then becomes distracted by The Yardbirds performance, and the piece of guitar that suddenly becomes meaningless when he leaves the nightclub. It seems that Thomas is a person of little consistency - he'll love you for a few hours, but then he'll be off elsewhere. He'll buy your artwork, and then forget about it. He'll photograph the poor, and then he's done with them. Was this Antonioni's statement about swinging London? That it was all fads, and moments, and that there was little depth and consistent follow-through on the philosophical trends of the day? It doesn't connect neatly with the whole "reality" picture, but it was there so often I kept on being reminded about the presence of "distraction".

I wanted this to be brief, I have far too much to say about this film - the cinematography by Carlo Di Palma (great use of colour, which Antonioni seems to have grasped as soon as he started making colour films - this was his second) almost seems beside the point. It's not though - there are several instances when we're explicitly told that we're not seeing this from any other perspective aside from the director. Thomas looks - and we ourselves look, but we're not Thomas. Interestingly, Di Palma was often used by Woody Allen later in his career. The music of Herbie Hancock has such a gentle touch in most places you won't even realise it's making light melodic differences when it's playing. When Thomas drives in London, going by so many colourful buildings - were they painted on the insistence of an eccentric filmmaker? Perhaps. It's a vibrant, very alive movie - and oh so colourful - wonderfully colourful. The sound is crisp and clear, and nothing ever seems like it has a heavy touch.

Quickly, I wanted to mention what the film itself mentions about purpose and art. There's at one stage an explicit mention of the fact that if an object no longer has a purpose, then it's art - I really loved that little nod. Thomas buys a propeller, admittedly beautiful, and without it's original purpose it will adorn his studio as a work of art. I think it works the other way as well. Once Thomas discovers a murder in his photographs, they no longer exist as the art they were meant to be. They're evidence, and they're clues - they suddenly define a different version of reality. They have a purpose. But when the artist in this instance, Thomas, tried to communicate and act, he stumbled and was distracted and failed to share this reality with anyone. They disappeared. The body disappeared. In the end, even Thomas himself disappears. He never existed. The murder never happened. I think Antonioni was thinking a lot about the process he goes through in making a film, and more specifically, a film as a work of art. What it means to him, to us, and what part of the whole process is "real" in an objective way, then subjective way for all of us. In doing that, he really created an eternal masterpiece that will never disappear.

Blow-Up - 1966

Directed by Michelangelo Antonioni

Written by Michelangelo Antonioni & Tonino Guerra

Based on a short story by Julio Cortázar

Starring David Hemmings, Vanessa Redgrave & Sarah Miles

I have a pet theory about auteur films that have great interpretive scope. I believe a filmmaker and screenwriter can make one without knowing which interpretation they're aiming for - and further, that the less the person making the film knows what it's about, the better the film. It takes a person's subconscious to weave a good dream-rug made from metaphor, overtone, parable and connotation. We've all seen the opposite - clunky, awkward movies that are heavy-handed and leave little room for analysis. Films full of dead-certain giveaways. Blow-Up, Michelangelo Antonioni's surprisingly popular first English language film, has been debated and commented upon ever since it was released, over 50 years ago. There's no definitive word on what it's about - exactly. It speaks to us in the same way dreams speak to us, and as such it's an enjoyable sport to interpret and analyse. Most of what I have to say about the film is my own personal take-away from it, and is not meant as a definite and definitive guide, obviously.

In Blow-Up we have central character Thomas, a high-end, high-priced photographer that works taking pictures that appear everywhere in the cultural epoch of 1960s London. He drives a Rolls Royce, and lives a life of debauched freedom - taking photographs that speak about a reality that he sees, and tries to experience. One day, he takes pictures of a young woman and older man frolicking in the park - and the woman proceeds to beg him to either destroy the negative or hand it over to her. Thomas, piqued by the possible value his pictures have, and the power they give him over the woman in question, keeps them. When he develops the photos, he notices a shape in the bushes off to the right, and as he blows it up larger, and larger, he can see the shape of a man who appears to be holding a gun. Later, one of the last photographs he had taken is also enlarged - and shows the man in the park collapsed onto the ground. He goes to the park to investigate, and finds the dead body, but before he can formulate any kind of action his pictures, negatives and the body slip through his fingers. With no evidence - how can Thomas ever prove it really happened?

Everything that happens, and every line of dialogue, is very suggestive in Blow-Up - not a moment is wasted not conveying some kind of important meaning and as such you're never left to just tread water. When I watch it I'm constantly thinking, "...and what did that mean?" When the film makes a point of going on a detour, you know it isn't just wasting our time. Most interesting to me is when, early in the film, Thomas talks to a painter who, in explaining his work, says “They don't mean anything when I do them. Afterwards, I find something to hang onto. Like that leg,” and he points to a leg that can only just be made out in a very surreal image. This seems to not only be a statement about the film and reality, but also directly illuminates what Thomas is doing when he's blowing up his photographs. Hell, it's how I interpret the movie as well - finding something to hang onto so I can start formulating some kind of larger purpose. That's what I'll do here, I'll take the obvious instances of explicit meaning and see if I can tie it all together. Aside from the more outwardly real aspects, such as how much Thomas enjoys the power he has over people looking for fame, fortune or the need to hide what he captures with his camera - a device that never lies - or does it?

First up, I'll take what comes last in the film. There's a significant and lengthy scene to finish it off which features Thomas watching a group of mimes playing a kind of "mime tennis", pretending there's a ball. At one stage the mimes pretend the ball has gone over the fenced enclosure, and ask Thomas to continue the performance by running after the invisible ball, and "returning" it - which he does, now fully invested in the performance himself. All of this is obviously alluding to the nature of shared reality, and also the sharing of a reality that's not objectively real. Now, we go back to the beginning of the film - Thomas was dressed up in dirty bum-clothes, pretending to be a penniless wino living in a doss house. Why? So he could mingle and take naturalistic photographs of what goes on in there. We have that duality of realities there as well. While Thomas is in there, in dirty clothes, he's indistinguishable from any other person in there. You could well say he's one of them at that moment - but objectively he's not. He's a rich photographer. So, those things must be important to the film. Shared reality, objective reality and the interesting question posed - does a shared belief constitute some kind of reality, even if it's not objectively real?

The models Thomas takes photographs of are also a good illustration of that fine line. They don't own the expensive clothes they're wearing, and their expressions do not convey what they're thinking. When you look at them in magazines, they look real - but very little of what you're seeing is. In fact, only the physical image. So, an interpretation of a photograph cannot be considered objective reality without some kind of confirmation. What about art? What's real there? What constitutes reality? Reality is what the artist friend of Thomas begins with - "That's a leg." It's what you recognize. A gun. A leg. A person. A tree. Now, look at what happens to Thomas and his park photographs. The first thing we all recognize is a man and a woman. Lovers. Play. Sex. An affair perhaps? They're alone. But when Thomas looks closer it all breaks down. He finds something else to "hang onto" - a man with a gun. It changes the reality completely. Like Thomas in the doss house, this was just dressed up - a pretend fling for the woman. The reality is now a conspiracy. For Thomas, reality has changed - he looked closer.

If reality itself can change for Thomas when he looks closer, what does that say for all of us? Just look at Sir Isaac Newton, who had seemingly unlocked the secret of gravity. From that moment on, the reality for everyone science-minded had been defined. Then Albert Einstein looked closer, much like Thomas does. Then reality - for everyone - changed. If that can happen, how can we ever think of reality as anything other than something impermanent? Elusive? We hunger for something eternal - something that's some kind of bedrock. Turns out reality - whatever it is for us - is a shifting phenomenon. We can reach out and grasp onto things - "That's a leg" and "That's a dog," but when we cast our eyes around, constantly and insistently defining our reality, our mind often tricks us into the comfort of thinking that we're on top of it. Look at what the girl says in that famous quote towards the end. "I am in Paris" - it perfectly illustrates all of this. Her reality is different - like in 1984, where O'Brien says "The Law of Gravity is nonsense. No such law exists. If I think I float, and you think I float, then it happens." Does objective reality even exist, if it's not being percieved? Is there such a thing?

So, there's one important part of Blow-Up that I've been trying to add to this meaning. Throughout the film, there are constant instances of distraction. Distraction is a huge part of the puzzle. When the mysterious woman is with Thomas, he's distracted by the arrival of the propeller he bought. When he's figuring out his blown-up photograph, the two girls arrive and distract him from examining them further, and acting on the information. When he sees the mysterious woman again, he chases her through London, and then becomes distracted by The Yardbirds performance, and the piece of guitar that suddenly becomes meaningless when he leaves the nightclub. It seems that Thomas is a person of little consistency - he'll love you for a few hours, but then he'll be off elsewhere. He'll buy your artwork, and then forget about it. He'll photograph the poor, and then he's done with them. Was this Antonioni's statement about swinging London? That it was all fads, and moments, and that there was little depth and consistent follow-through on the philosophical trends of the day? It doesn't connect neatly with the whole "reality" picture, but it was there so often I kept on being reminded about the presence of "distraction".

I wanted this to be brief, I have far too much to say about this film - the cinematography by Carlo Di Palma (great use of colour, which Antonioni seems to have grasped as soon as he started making colour films - this was his second) almost seems beside the point. It's not though - there are several instances when we're explicitly told that we're not seeing this from any other perspective aside from the director. Thomas looks - and we ourselves look, but we're not Thomas. Interestingly, Di Palma was often used by Woody Allen later in his career. The music of Herbie Hancock has such a gentle touch in most places you won't even realise it's making light melodic differences when it's playing. When Thomas drives in London, going by so many colourful buildings - were they painted on the insistence of an eccentric filmmaker? Perhaps. It's a vibrant, very alive movie - and oh so colourful - wonderfully colourful. The sound is crisp and clear, and nothing ever seems like it has a heavy touch.

Quickly, I wanted to mention what the film itself mentions about purpose and art. There's at one stage an explicit mention of the fact that if an object no longer has a purpose, then it's art - I really loved that little nod. Thomas buys a propeller, admittedly beautiful, and without it's original purpose it will adorn his studio as a work of art. I think it works the other way as well. Once Thomas discovers a murder in his photographs, they no longer exist as the art they were meant to be. They're evidence, and they're clues - they suddenly define a different version of reality. They have a purpose. But when the artist in this instance, Thomas, tried to communicate and act, he stumbled and was distracted and failed to share this reality with anyone. They disappeared. The body disappeared. In the end, even Thomas himself disappears. He never existed. The murder never happened. I think Antonioni was thinking a lot about the process he goes through in making a film, and more specifically, a film as a work of art. What it means to him, to us, and what part of the whole process is "real" in an objective way, then subjective way for all of us. In doing that, he really created an eternal masterpiece that will never disappear.