← Back to Reviews

in

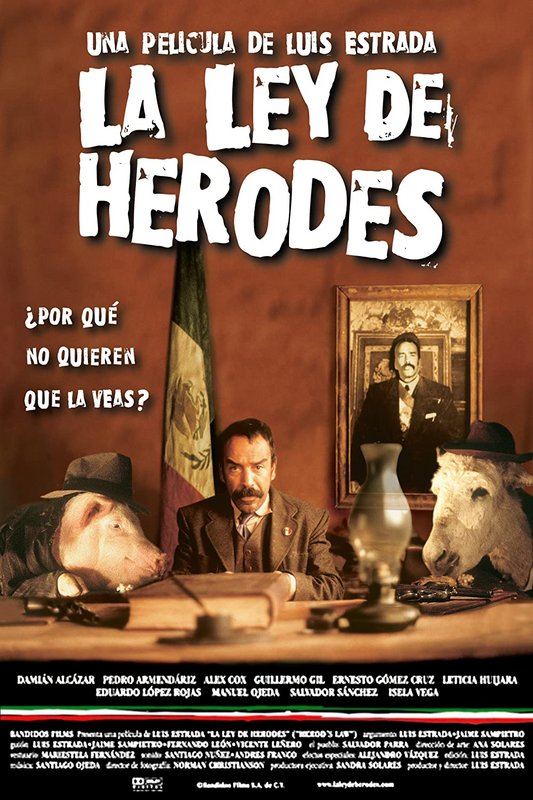

Herod's Law (La ley de Herodes) - 1999

Directed by Luis Estrada

Written by Luis Estrada, Jaime Sampietro, Fernando León & Vicente Leñero

Starring Damián Alcázar, Pedro Armendáriz Jr., Delia Casanova, Juan Carlos Colombo

& Alex Cox

It's nice to watch a film as straightforward as Herod's Law, with it's basic premise being "this is how corruption works" - from innocence to unscrupulousness, step by step. It's a comedy, and it's one I keep on mistakenly thinking of as an analogy, despite the way it directly shows the corruption of a Mexican politician. It's kind of both - told in an analogous and direct manner. It's obviously very satirical, and approaches it's serious subject in a funny kind of way - otherwise it would be possible that the various murders, prostitution, violence and moral repugnance might make the film too dark and foreboding to really enjoy. Our protagonist, Juan Vargas (Damián Alcázar) seems strangely likeable, despite the fact he turns out to be a complete monster by the end of the story that's being told here. This is the kind of film that's telling us that any human being is inevitably turned into a completely corrupt tyrant in an authoritarian regime such as the one Mexico had for most of the 20th Century - the PRI (Institutional Revolutionary Party).

Juan Vargas is the new mayor of San Pedro de los Saguaros, a small Mexican town whose previous mayor was chased down by angry townspeople and beheaded due to his sheer corruptness. Juan, and his wife Leticia Huijara (Leticia Huijara) have dreams of promotion, and clearly want to help the townspeople by governing well. Juan's first problem is the existence of a brothel, which is illegal and at which a dead body has shown up. When Juan tells the owner of the brothel, Doña Lupe (Isela Vega) that she's to shut it down, she counters with a series of attempted bribes, which get larger the more Juan insists on doing things by the book. That's not the only problem - the town itself is broke, and when Juan travels to see his bosses, López (Pedro Armendáriz Jr.) and his assistant (played by Juan Carlos Colombo) they have no funds to give him, but do send him on his way with a pistol, and the Mexican Constitution. Lawbreakers will provide the town's funds, in fines. At this time Juan also meets Robert Smith, an American, and the two will try to cheat each other constantly. Once Juan starts fining townspeople, and taking bribes, he soon realises that there is a mountain of money to be made, and the road to corruption and murder begins...

An example of an analogy in this film is the one of people and nations - when Juan meets Robert Smith, the latter obviously represents the United States as a whole, and during their interactions, Juan represents Mexico. Smith wants to overcharge Juan for a simple repair on his car (so simple as to not really even be a "repair"), and in answer to being cheated, Juan politely agrees, but then continually stalls when it comes to actually paying him anything. The two continue on like this, and instead of a situation that could be mutually beneficial, the two get nowhere together. All we get is a continual polite negotiation where the two smile and act like friends, while continuing with their underhanded tactics of trying to gain advantage. While I watched the film I thought that this was a perfect example of international negotiations, and although I don't know a lot about how the United States and Mexico comport themselves when there's dialogue between them, it's safe to assume that polite agreements and constant maneuvering for unfair advantage take place.

One other interesting subject explored in the film is the inevitability of bribes working in illegal enterprises that make large sums of money in a poor country. When the people you're meant to be policing can pay you ten to a hundred times more than you earn doing your job, chances are you'll work for the criminals - especially if you're being driven into poverty by the powers that be. The same goes for preying on the defenseless through unfair legislation and taxation, which is what Juan eventually does in this film. He finds that the gun and the rule book are a combination that can make you rich beyond your wildest imaginings, and at a certain point riches turn an honest man into an insatiable monster. It's no surprise that power corrupts, and yet we keep expecting it not to. When we meet Juan Vargas he seems to be such a nice, simple-minded man that you'd never expect him to do the things he eventually does. It's a step by step process, the first of which is what it feels like to have real money in your hands, and what it feels like for Juan to have control over prostitutes who have to do his bidding. Power changes him completely, for his release from his previous chains is one of ecstacy.

Writer and director Luis Estrada was nominated for and won various awards for Herod's Law, which was an incredibly brave undertaking. Nobody had challenged or criticized the PRI since it's conception in Mexico 70 years previously, and to do so risked a punishment that could only be guessed at. Assassination? Jail? In a corrupt nation, anything is possible. Once they knew what they had on their hands, the Mexican Film Institute, run by the government, tried to hold back it's release and limit the number of theaters it was shown in, but this had the unintended effect of making Mexicans even more curious about it, so in the end the film was left alone and was a success. People in Mexico are well used to living with corruption, but it was refreshing for the truth to be openly acknowledged in film. Damián Alcázar is really energetic in the lead role, and his comedic timing is spot on. Santiago Ojeda's score is light and easy in a 'comedic' style, keeping the tone from becoming too dark. The film as a whole has a dirty and dusty look to it - everything is worn out, filth-encrusted and most of all, poor.

As for the rest, we also have a priest (played by Guillermo Gil) which, in this parable, represents the fondness the church has for extorting as much money as it can from it's parishioners and the government. There are also good men in this town. The doctor/coroner Morales (Eduardo López Rojas) who complains once too often about the corruption endemic to the area, and is sent packing. Then there is Carlos Pek (Salvador Sánchez) who is secretary to Juan Vargas - he speaks the language of the Indian natives, and is therefore their impotent mouthpiece. The native dwellers have been left to their alcoholic escape from their desperate and threadbare existence, dressed in rags and with little to eat. They sleep in the street, and are found either dead or comatose with a bottle when passed by. Pek, the secretary, stands as a confounded, powerless spectator to the drama which plays out. He can do nothing as Juan transforms from hopeful idealist to savage opportunist, and as Juan has the gun and all the power, nobody else can do much about it either.

I enjoyed this little fable which illustrates a kind of natural progression from good to bad under a system that relies on the gun and lawbook to disenfranchise the masses and deliver power and riches to those fortunate enough to hold onto both. Of course, you must remember that many of the mayors San Pedro de los Saguaros has had ended up killed by an angry mob, but you also have to remember that Juan Vargas ends up not with a noose around his neck, but in high office. The last time we see him, he's giving a disingenuous speech in the Mexican Senate, all about the people, with little recognition of how corrupt and poverty-stricken the nation is, and with little regard to his murderous and corrupt reign in the little town he robbed. It's not that Mexico needs better leaders, it's the system itself that is broken, and will always deliver unto itself crooks and thieves because it can only work through theft, greed and armed power. Honest politicians can't work the system, so they can either give up their political career or join the ranks of bribe-takers and criminals. People shouldn't be focused on a change of leaders as much as they should focus on a change of systems - that rings true for many, if not most, nations, and perhaps the best way to do that is little by little, for large scale revolutions often only deliver chaos which can be exploited by sharp-minded crooks and deceivers.

Herod's Law (La ley de Herodes) - 1999

Directed by Luis Estrada

Written by Luis Estrada, Jaime Sampietro, Fernando León & Vicente Leñero

Starring Damián Alcázar, Pedro Armendáriz Jr., Delia Casanova, Juan Carlos Colombo

& Alex Cox

It's nice to watch a film as straightforward as Herod's Law, with it's basic premise being "this is how corruption works" - from innocence to unscrupulousness, step by step. It's a comedy, and it's one I keep on mistakenly thinking of as an analogy, despite the way it directly shows the corruption of a Mexican politician. It's kind of both - told in an analogous and direct manner. It's obviously very satirical, and approaches it's serious subject in a funny kind of way - otherwise it would be possible that the various murders, prostitution, violence and moral repugnance might make the film too dark and foreboding to really enjoy. Our protagonist, Juan Vargas (Damián Alcázar) seems strangely likeable, despite the fact he turns out to be a complete monster by the end of the story that's being told here. This is the kind of film that's telling us that any human being is inevitably turned into a completely corrupt tyrant in an authoritarian regime such as the one Mexico had for most of the 20th Century - the PRI (Institutional Revolutionary Party).

Juan Vargas is the new mayor of San Pedro de los Saguaros, a small Mexican town whose previous mayor was chased down by angry townspeople and beheaded due to his sheer corruptness. Juan, and his wife Leticia Huijara (Leticia Huijara) have dreams of promotion, and clearly want to help the townspeople by governing well. Juan's first problem is the existence of a brothel, which is illegal and at which a dead body has shown up. When Juan tells the owner of the brothel, Doña Lupe (Isela Vega) that she's to shut it down, she counters with a series of attempted bribes, which get larger the more Juan insists on doing things by the book. That's not the only problem - the town itself is broke, and when Juan travels to see his bosses, López (Pedro Armendáriz Jr.) and his assistant (played by Juan Carlos Colombo) they have no funds to give him, but do send him on his way with a pistol, and the Mexican Constitution. Lawbreakers will provide the town's funds, in fines. At this time Juan also meets Robert Smith, an American, and the two will try to cheat each other constantly. Once Juan starts fining townspeople, and taking bribes, he soon realises that there is a mountain of money to be made, and the road to corruption and murder begins...

An example of an analogy in this film is the one of people and nations - when Juan meets Robert Smith, the latter obviously represents the United States as a whole, and during their interactions, Juan represents Mexico. Smith wants to overcharge Juan for a simple repair on his car (so simple as to not really even be a "repair"), and in answer to being cheated, Juan politely agrees, but then continually stalls when it comes to actually paying him anything. The two continue on like this, and instead of a situation that could be mutually beneficial, the two get nowhere together. All we get is a continual polite negotiation where the two smile and act like friends, while continuing with their underhanded tactics of trying to gain advantage. While I watched the film I thought that this was a perfect example of international negotiations, and although I don't know a lot about how the United States and Mexico comport themselves when there's dialogue between them, it's safe to assume that polite agreements and constant maneuvering for unfair advantage take place.

One other interesting subject explored in the film is the inevitability of bribes working in illegal enterprises that make large sums of money in a poor country. When the people you're meant to be policing can pay you ten to a hundred times more than you earn doing your job, chances are you'll work for the criminals - especially if you're being driven into poverty by the powers that be. The same goes for preying on the defenseless through unfair legislation and taxation, which is what Juan eventually does in this film. He finds that the gun and the rule book are a combination that can make you rich beyond your wildest imaginings, and at a certain point riches turn an honest man into an insatiable monster. It's no surprise that power corrupts, and yet we keep expecting it not to. When we meet Juan Vargas he seems to be such a nice, simple-minded man that you'd never expect him to do the things he eventually does. It's a step by step process, the first of which is what it feels like to have real money in your hands, and what it feels like for Juan to have control over prostitutes who have to do his bidding. Power changes him completely, for his release from his previous chains is one of ecstacy.

Writer and director Luis Estrada was nominated for and won various awards for Herod's Law, which was an incredibly brave undertaking. Nobody had challenged or criticized the PRI since it's conception in Mexico 70 years previously, and to do so risked a punishment that could only be guessed at. Assassination? Jail? In a corrupt nation, anything is possible. Once they knew what they had on their hands, the Mexican Film Institute, run by the government, tried to hold back it's release and limit the number of theaters it was shown in, but this had the unintended effect of making Mexicans even more curious about it, so in the end the film was left alone and was a success. People in Mexico are well used to living with corruption, but it was refreshing for the truth to be openly acknowledged in film. Damián Alcázar is really energetic in the lead role, and his comedic timing is spot on. Santiago Ojeda's score is light and easy in a 'comedic' style, keeping the tone from becoming too dark. The film as a whole has a dirty and dusty look to it - everything is worn out, filth-encrusted and most of all, poor.

As for the rest, we also have a priest (played by Guillermo Gil) which, in this parable, represents the fondness the church has for extorting as much money as it can from it's parishioners and the government. There are also good men in this town. The doctor/coroner Morales (Eduardo López Rojas) who complains once too often about the corruption endemic to the area, and is sent packing. Then there is Carlos Pek (Salvador Sánchez) who is secretary to Juan Vargas - he speaks the language of the Indian natives, and is therefore their impotent mouthpiece. The native dwellers have been left to their alcoholic escape from their desperate and threadbare existence, dressed in rags and with little to eat. They sleep in the street, and are found either dead or comatose with a bottle when passed by. Pek, the secretary, stands as a confounded, powerless spectator to the drama which plays out. He can do nothing as Juan transforms from hopeful idealist to savage opportunist, and as Juan has the gun and all the power, nobody else can do much about it either.

I enjoyed this little fable which illustrates a kind of natural progression from good to bad under a system that relies on the gun and lawbook to disenfranchise the masses and deliver power and riches to those fortunate enough to hold onto both. Of course, you must remember that many of the mayors San Pedro de los Saguaros has had ended up killed by an angry mob, but you also have to remember that Juan Vargas ends up not with a noose around his neck, but in high office. The last time we see him, he's giving a disingenuous speech in the Mexican Senate, all about the people, with little recognition of how corrupt and poverty-stricken the nation is, and with little regard to his murderous and corrupt reign in the little town he robbed. It's not that Mexico needs better leaders, it's the system itself that is broken, and will always deliver unto itself crooks and thieves because it can only work through theft, greed and armed power. Honest politicians can't work the system, so they can either give up their political career or join the ranks of bribe-takers and criminals. People shouldn't be focused on a change of leaders as much as they should focus on a change of systems - that rings true for many, if not most, nations, and perhaps the best way to do that is little by little, for large scale revolutions often only deliver chaos which can be exploited by sharp-minded crooks and deceivers.