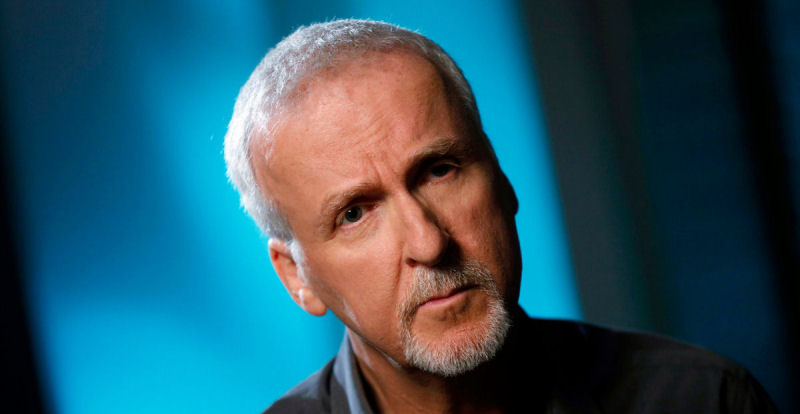

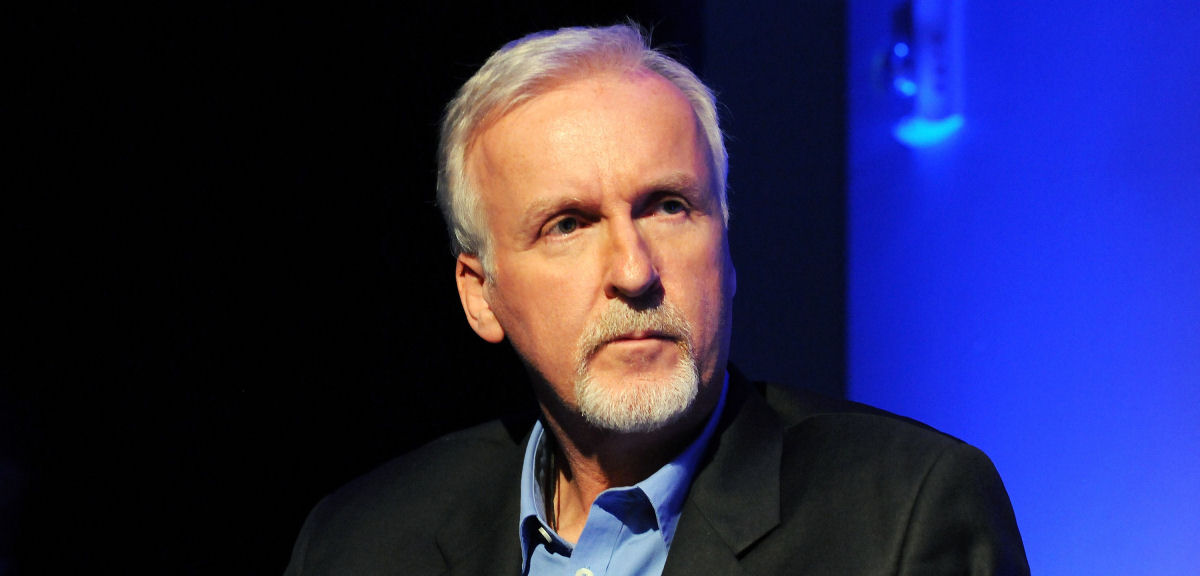

James Cameron Probably Hates You

It is a common sentiment that the most successful blockbusters are simplistic, crowd-pleasing affairs. The hero always gets the girl, the good guys always win, and humanity triumphs over the forces of whatever.

When you look at some of history's most successful films, however, there are some notable exceptions. Until recently, the two films at the top of the list (in nominal terms) were Avatar and Titanic, both directed by one James Cameron. Neither film fits the typical blockbuster mold, and as you peruse the rest of Cameron's lucrative filmography, it becomes obvious that virtually nothing he's worked on does.

It began with Xenogenesis, a short sci-film about finding a new planet on which to start the life cycle, presumably because Earth is used up and/or uninhabitable. Like much speculative fiction, it's dystopian, though not especially so. It wasn't completed and garnered little attention.

Cameron's next effort, 1984's The Terminator, was his breakthrough, and it had a critique of humanity's self-destructive nature at its core. He followed that up with another hit, 1986's Aliens, a sequel custom made for his already established interest in sci-fi and nihilism. Aliens takes the themes of corporate greed and indifference to humanity found in the first film and shoves them into the foreground.

In 1989, Cameron released The Abyss. At first glance, this appears to be an exception to the rule. The setup is that the military needs to use a deep-sea mining station to inspect the wreckage of a submarine; the antagonist is a soldier who's gone insane from pressurization. Pretty mild, as far as humanity-condemning metaphors go.

This, however, was not Cameron's original vision of the film. In the Director's Cut, a significant amount of footage is added, nearly all of which is about the nuclear standoff taking place between the United States and Russia over the lost submarine. The starkest addition is a heavily extended finale where Bud (Ed Harris) discovers the deep-sea creatures' city and they show him a series of images emphasizing man's destructive nature, taking an elegant implication and making it unnecessarily overt to drive the point home.

Ultimately, the creatures decide that humanity is still worthwhile on the strength of Bud's loving messages to his wife, but the ratio of screen time given to nihilistic thoughts as opposed to hopeful ones is heavily skewed. This disparity is underlined in many critical responses to the film; though critics largely praised the effort as a whole (singling out the groundbreaking special effects), the most common complaint throughout its negative reviews was the sudden, inexplicable nature of the ending, presumably because it contrasted so awkwardly with the pessimistic tone exhibited throughout. The Director's Cut explains this disconnect. And so does the director himself:

“That's the movie. You go down to confront the aliens and all they do is hold up a mirror and show you how f**ked up you are.”

Of course, "the aliens" were written by Cameron, so the mirror is his films, and the people being confronted are his audiences.

That confrontation continued in 1991 when Cameron returned to the property that made him famous, with Terminator 2: Judgment Day. As was the case in Aliens, the message takes priority over the art, with otherwise subtle themes obstructed by giant doom-looping jumbotrons, lest someone manage to enjoy the sugary thrills without the bitter aftertaste of existential despair.

The most overt example comes when John Connor (Edward Furlong) stops to observe two children play fighting with toy guns. The camera lingers and the motion slows as we watch them try to "kill" each other. A less monomaniacal director would've probably left it at that. But the scene keeps going.

"We're not going to make it, are we?," Connor asks. And again, Cameron has a chance to stop here, leaving us with a statement that could be read as a commentary on the protagonists' chances of success and the future of mankind. But again, the scene keeps going.

"People, I mean," Connor adds. At this point there is no more subtext and the dual-meaning has collapsed into a single entendre. And yet, somehow, the scene continues.

"It is in your nature to destroy yourselves," the Terminator replies. And now we've fallen from "show don't tell" to "show, then tell, then tell again." Just in case you didn't glean the message from the story itself, or hearing it explicitly stated, Cameron makes sure to scrawl it on a 2x4, hit you over the head with it, then drag your body next to a billboard he's purchased with the same message on it so that it's the first thing you see when you wake up.

You'd think this would be the pinnacle of Cameron's nihilism, but like that scene, somehow it keeps on going. 1997's Titanic represents a rare departure from sci-fi, but the misanthropy is still there, and in fact has graduated from symbolism to slander.

The real story of the Titanic, apart from the now legendary hubris displayed by its creators, is one of heroism. As it became clear that the ship would need to be evacuated, the ship's officers made a point to allow women and children to enter the life rafts first. Men were lined up on the deck, patiently waiting their turn, one of whom was even shot for stepping out of place. Such order and honor in the midst of such a panic-inducing situation is remarkable to the point of sounding like fiction, and would seem ideal fodder for the cinema.

But in Cameron's retelling, the ship's sinking is marked by rampant chaos. Cowardly men push and shove women out of the way, lower-class citizens are left to drown in the lower decks, and the passengers' collective behavior makes one ashamed to be counted among the same species.

Creative liberties are common in the movies, but Cameron's mutilation of history was so bad that he was forced to apologize for it. Cameron's film depicts First Officer William Murdoch (an actual person) as shooting two people in a panic, then committing suicide. But according to testimony from other survivors, Murdoch did not kill himself, and there doesn't appear to be any evidence that he shot innocent people, either. To offset the immortalization of Murdoch's fictional disgrace, both Cameron and the Vice President of Fox at the time apologized to Murdoch's family, and a £5,000 charitable donation was made in his name.

Both the apology and donation, however, appear to have been done out of sheer expediency, rather than genuine remorse: in the film's DVD commentary track, Cameron attempts to defend himself by saying no one could prove that it didn't happen, which is both fallacious reasoning and a particularly odd defense for an avowed atheist to employ. He then argues himself into a corner by claiming that some officers did fire shots to maintain the "women and children first" policy. The fact that they did this to specifically prevent the injustice of people stealing the spots of women and children—which contradicts his film—seems to have been lost on Cameron.

That Cameron seems irredeemably drawn to pessimistic tales of humanity's flaws is telling, but most directors find themselves returning to the same themes. What sets this apart is that, when confronted with an historical counterpoint to his views in the behavior of those on the Titanic, Cameron simply refused to put it on film and concocted a version of history more in line with his worldview. It is one thing to take a low view of people, or to find their destructiveness interesting; it is quite another to try to bend reality when it contradicts you, let alone exhibit defiance when the falsehood is exposed. This sounds less like a viewpoint than a pathology.

Twelve years later, Cameron released Avatar, a recycling of both American guilt tropes and the humanity-runs-out-of-resources premise of his debut film, Xenogenesis, from decades earlier.

Some of these criticisms may seem harsh, but Cameron's distaste for humanity has manifested itself in tangible ways, both on set and off, through every film he's worked on and just shy of half a dozen marriages. A slew of collaborators have said he's the hardest person they've ever had to work with. Here's a far-from-comprehensive list of some of the things that have happened on Cameron's sets:

- A disgruntled crew member on Titanic stabbed him in the face with a pencil.

- Another disgruntled crew member appears to have poisoned his soup with PCP; Cameron and dozens of others were taken to the hospital.

- The late Bill Paxton referred to the process of working with him as "indentured."

- Ed Harris nearly drowned during a take on The Abyss, burst into tears, may have punched him, and refused to help promote the film.

- The crew of Aliens walked out on him after he had a dispute with a cameraman.

"This has been a long and difficult shoot, fraught by many problems. But the one thing that kept me going, through it all, was the certain knowledge that one day I would drive out the gate of Pinewood and never come back, and that you sorry bastards would still be here."

Even the handful of positive marks he's received (from the few people he's worked with more than once) are heavily qualified. Sigourney Weaver, arguably representing Cameron's longest ongoing relationship of any kind, praises only his perfectionism, and excuses the fact that "he really does want us to risk our lives and limbs for the shot" because "he doesn't mind risking his own."

Art Imitating Life

The most elegant parallel in Cameron's career isn't on the page or the screen, but in the way his personal beliefs mirror his cinematic tendencies. Though often lacking in story and dialogue, Cameron's films find success through sheer scope and technological ambition. They are works of scale more than works of art.

This formula is the same one Cameron proposes we use to save the species: in 2000, addressing an assembly celebrating Earth Day, he remarked:

"I just want to say that we're all doomed, but on the positive side, we created this impending doom ourselves, with our brains, with our technology, and we can damn well uncreate it."

If you think this sounds weirdly hopeful alongside everything else you've read, don't worry, it's offset by his religious beliefs, which are openly hostile towards other viewpoints. Cameron's atheism is among the more militant varieties; he refers to agnosticism as "cowardly" and wrote the foreword to The Jesus Family Tomb, a book which contends that Jesus was a normal man and that His remains have already been discovered. The book was adapted into a documentary called The Lost Tomb of Jesus, of which Cameron was the Executive Producer. For Cameron, technology is a religion, and he regards it as our only savior.

And it's a religion he's already been martyred for: according to i09, reviewing a book about Cameron, he "won every academic award in ninth grade and became president of the Science Club, and not surprisingly got himself beat up by all the other kids in the process," seemingly explaining both his techno-worship and his low view of people in one compact anecdote.

It may seem crude to tie a man's work to his upbringing and worldview so readily, but in Cameron's case the connections are so clear and obvious that we're obliged to notice them. If I were to describe a woman who "spent her weekends in fatigues and combat boots, learning to assemble a rifle while blindfolded," you'd probably think of Linda Hamilton as Sarah Connor. In reality, the description is of Cameron's mother Shirley, who joined the Canadian Women's Army when he was a child.

James Cameron is not the first filmmaker to have a favored theme, abuse his crew, or work through his personal issues in front of audiences. But the confluence of all three, and the seeming inability to tell stories about anything else even when reality contradicts him, makes for a strikingly morose filmography that contrasts with most of the industry's biggest blockbusters.

And it's difficult not to be cynical about the money they make. This is a career imbued with a deep, pervasive misanthropy, smuggled into theaters under special effects and obscured by 3D glasses. As the culture sharpens and coarsens, it has to be asked whether the success of such pessimistic films is part of the symptom, or part of the disease. Because while all art is a product of the culture it's created in, it also influences it. If you stare long enough into The Abyss, The Abyss stares into you.

Discuss this Essay (115 comments)

Thanks for the context. I don't have any trouble believing that played a part, though Cameron's reaction still seems pretty over the top. And the fact that he's had similar run-ins with basically ever... Read Comment

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0090605/trivia/ Actor Bill Paxton later said that this British film crew drove everyone nuts with their "indentured work ethics", literally s... Read Comment

Yeah, sometimes it seems like he's building entire movies around the tech he wants to play around with.... Read Comment