← Back to Reviews

in

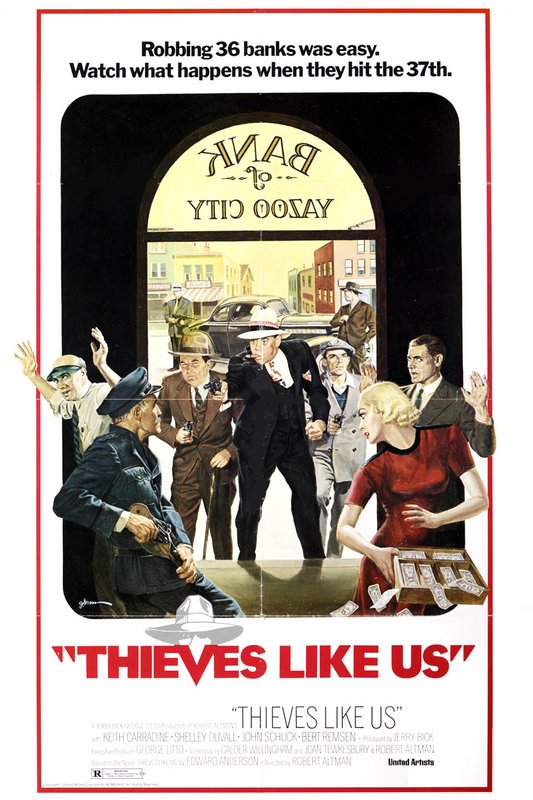

Thieves Like Us - 1974

Directed by Robert Altman

Written by Joan Tewkesbury

Based on the novel "Thieves Like Us" by Edward Anderson

Starring Keith Carradine, Shelley Duvall, John Schuck, Bert Remsen

Louise Fletcher & Tom Skerritt

In an article titled "Love and Coca-Cola", Pauline Kael wrote that Thieves Like Us was perhaps the "closest to flawless of Altman's films - a masterpiece." It certainly has a puzzlingly low profile for such a great piece of cinematic art. It's a film that is what it is - there's no pretense to any deeper meanings you'd ascribe to it that don't fit the main narrative, and it's a film of it's time, with Bonnie and Clyde setting the tone in 1967 for period-rich bank robbing outlaw films set in depression era America. The way Altman has worked Edward Anderson's novel (for once adapted faithfully by a filmmaker notorious for doing otherwise) puts us in the picture - the characters aren't oversized mythical figures, as they are in Arthur Penn's classic along with the likes of Dillinger (1973) or Big Bad Mama (1974) which come from this same era. Instead we're transported by way of radio, lush cinematography and clever production design to a place and time that almost feels familiar. It feels like the most assured film from one of the most assured directors of his time - and it's another classic 1970s Altman film that I absolutely love.

Young and good natured Bowie (Keith Carradine), the big bodied Chicamaw (John Schuck) and older "T-Dub" (Bert Remsen) escape from a Mississippi prison after being appointed trustees by hijacking a taxi - it's 1936, and the three hide out at the auto-repair garage owned by Dee Mobley (Tom Skerritt) and his daughter Keechie (Shelley Duvall). There, they plan their next meet-up, which will lead to another bank robbery and another hide-out, this time at the home of relative Mattie (Louise Fletcher - in her first feature film role.) When they leave this time, Bowie is involved in a particularly nasty traffic accident, and Chicamaw must shoot two lawmen dead to escape the scene without being apprehended. Bowie recuperates back at Mobley's place, and it's while being looked after by Keechie that the two fall in love. They get themselves a place out of the way, and find an enjoyable pace of life - but when Bowie meets Chicamaw and T-Dub again, he robs another bank again - which results in another killing. With the heat from both the law and the general population becoming intense, and with Keechie falling pregnant, the young man has to hope he's making the right decisions if he's to survive and start a family.

Joan Tewkesbury had simply been a script supervisor on McCabe & Mrs. Miller when she was suddenly conscripted into the Altman filmmaking machine and asked to play a small role in the film. Now she was being asked by him to adapt Edward Anderson's 1937 novel and Altman's faith in her paid off - he was pleased enough with what she'd done that instead of continuing on his freewheeling ways, he'd stick to the script and story - while still allowing the actors to improvise lines in the context of individual scenes. It would be one of the first screenplays he'd not throw in the trash can - and when production on Thieves Like Us started Altman sent Tewkesbury to Nashville to investigate the country music scene up there for a film he was intending to make. In the end, Nashville (1975) would be based on her diary and experiences there. You can sense that Altman's instinctive intuition with Tewkesbury was right on the money, and although both Calder Willingham and Robert Altman would be given screenwriting credits, this is her movie. It was only after production had started that Altman would find out that the book had been adapted once already, as They Live by Night in 1948.

On this film, once again, he'd have his stable of regular performers comfortably playing their part, and helping to bring their characters alive - you can sense the depth they have, as if they're real living people. Keith Carradine, of the famous Carradine acting family, had debuted in McCabe & Mrs. Miller. John Schuck had been with Altman a while, and featured in M*A*S*H, Brewster McCloud and McCabe & Mrs. Miller. Bert Remsen had been part of Brewster McCloud's casting department when he was conscripted as an actor on the film - played his scene brilliantly, and found himself appearing in McCabe & Mrs. Miller before this. Shelley Duvall had been discovered by Altman in Texas and was introduced in Brewster McCloud to great effect. She also had a part in McCabe & Mrs. Miller - touchingly, also opposite the young Keith Carradine, making this a kind of sweet reunion for the two lovestruck characters. Tom Skerritt had appeared in M*A*S*H. The comfort and familiarity he had with his actors makes Altman's films as warm as they are. Louise Fletcher is fantastic in her role as well, and is very well cast as a prim, proper and strict housewife having to contend with a family that's either in prison or causing her trouble.

There had been a change in director of photography - French cinematographer Jean Boffety was behind the lens after a series of films Altman had done with Vilmos Zsigmond. It's my opinion that Boffety probably should have been given an Oscar nomination for the cinematography he's done on Thieves Like Us - it's such a visually lush film, full of the green topography of Mississippi and he captures this in many different ways from different perspectives. He also follows the lead of his director by shooting many scenes through windows and flywire - and past obstructions, giving us that voyeur's view and sense of diffusion. Of course, it wouldn't be an Altman film without the occasionally delightful zoom in or zoom out - now a kind of calling card that's instantly recognizable. Every shot - lengthy or short, long or close-up, is framed beautifully, and just looks extraordinarily good. I love the look Thieves Like Us has - aided by filming on location and not on sets. Boffety, not being from the U.S., felt compelled to take on the challenge of filming in Mississippi - a place most cinematographers like to avoid. The landscapes, tracking and dolly shots (including a wonderful, high-speed, road shot that was only possible because a new road had just been created parallel to an old one) all take on a note of perfection.

There's no score to the film - instead we get a consistent dose of 1936/7 radio as a background to everything that goes on in the film. It works really well, and aside from the music which helps to ground us in this place, time and circumstance there are many serials which involve crime and crime fighters, painting a picture of the national mood as far as gangsters and criminal activity is concerned. When Bowie and Keechie first start making love we get a radio adaptation of Romeo and Juliet that repeats as much as their lovemaking repeats. All wonderfully inventive and done with a filmmakers instinct that had no peer at the time. Thieves Like Us is a great film that was hardly promoted or noticed on release - and it's one that has yet to be properly discovered. You hear a collection of old songs and tunes, from the likes of Johnny Mercer, Victor Herbert, Irving Mills and Lew Brown. We simply roll along with our characters as the radio is on in the background, and it feels natural - but it's expertly guided and purposely arranged to fit the mood and circumstance of each moment.

The first time I watched Thieves Like Us it took me by surprise - I was expecting to see something more fringe from such a low-budget 1970s feature, but this has the feel of classic - a top of the line, wonderfully acted, beautifully captured film that is a pleasure to watch. The way the characters slowly change, from an almost adolescent immature happiness into three distinct characters that all have their troubling and fateful flaws, has a perfect timing to it. The rhythm, of the story and scenes, seems perfect. It's so appealing in it's sights and sounds. The story is hard-edged, but slants towards love, kinship and friendship to such a degree murders only register fully on Bowie's face, which we read so clearly that we trust him as a kind of moral arbiter - one that is ironically also a killer. There's no pretension - the film is made up of perfectly normal day-to-day moments of the innocuous which add up to something greater, and these moments are only briefly interrupted by events of more magnitude - and even the bigger moments play as everyday. It feels like the most honest, realistic and personal of depression-era crime thrillers.

Now, there's a product which dominates this film - Coca-Cola. The characters seem obsessed with it, and Coca-Cola advertisements are everywhere. There's even a Coca-Cola wagon that creeps along a street with a giant bottle of Coke in the back - and there are empty bottles of Coke, or else the characters are drinking Coke, in every scene. Emanuel Levy wrote that this represented an "icon of popular culture" and that Coke was "one of the few unifying objects in an increasingly diversified society" - that people of all classes could afford to drink it. He also said that this was "only a superficial equality" and functioned as a kind of "opium to the masses" - distracting them from the turmoil of depression era life in the 30s. He connects it to the superficial camaraderie the main characters have - and that becomes clearer as the film goes on and the characters solidify into three distinct people under pressure. However it's interpreted, it's one part of Thieves Like Us that stands out as interpretive and obviously being there for a reason. The story by itself is good enough to be entertaining, but there's that little iconography in the foreground of the film as an added bonus - one that could easily be misinterpreted as product placement, although a little too extreme even for that.

In the end it's another film which attains greatness in this 1970s Altman period - and while McCabe & Mrs. Miller has since received it's due, Thieves Like Us has continued to lurk in the background, remaining a film most people haven't seen. Bank robberies, the depression, guns and of course early 20th Century cars (usually with bullet holes) represent a newfound fascination with an era of crime that was unique to this time period - and I'd say that Thieves Like Us is my favourite film pertaining to this style and subject. It brings with it that Altman sense of grounded reality and applies it to subjects that were often mythologised. In through this walk the likes of Shelley Duvall, with her haunting eyes but jaunty tone, and the young fresh-faced Keith Carradine - all boyish charm and innocence despite having already shot someone to death before escaping prison. I've never seen the likes of characters such as these. Topping it off is how beautiful Mississippi looks in it's green resplendence, and how distinct American culture was as captured by a new national obsession - the radio. It makes for a film that should really have been a big hit - but it seems that this particular director confounded those operating the conveyer belt of cookie-cutter movies that were the opium of the masses back then. It deserves it's reconsideration.

Thieves Like Us - 1974

Directed by Robert Altman

Written by Joan Tewkesbury

Based on the novel "Thieves Like Us" by Edward Anderson

Starring Keith Carradine, Shelley Duvall, John Schuck, Bert Remsen

Louise Fletcher & Tom Skerritt

In an article titled "Love and Coca-Cola", Pauline Kael wrote that Thieves Like Us was perhaps the "closest to flawless of Altman's films - a masterpiece." It certainly has a puzzlingly low profile for such a great piece of cinematic art. It's a film that is what it is - there's no pretense to any deeper meanings you'd ascribe to it that don't fit the main narrative, and it's a film of it's time, with Bonnie and Clyde setting the tone in 1967 for period-rich bank robbing outlaw films set in depression era America. The way Altman has worked Edward Anderson's novel (for once adapted faithfully by a filmmaker notorious for doing otherwise) puts us in the picture - the characters aren't oversized mythical figures, as they are in Arthur Penn's classic along with the likes of Dillinger (1973) or Big Bad Mama (1974) which come from this same era. Instead we're transported by way of radio, lush cinematography and clever production design to a place and time that almost feels familiar. It feels like the most assured film from one of the most assured directors of his time - and it's another classic 1970s Altman film that I absolutely love.

Young and good natured Bowie (Keith Carradine), the big bodied Chicamaw (John Schuck) and older "T-Dub" (Bert Remsen) escape from a Mississippi prison after being appointed trustees by hijacking a taxi - it's 1936, and the three hide out at the auto-repair garage owned by Dee Mobley (Tom Skerritt) and his daughter Keechie (Shelley Duvall). There, they plan their next meet-up, which will lead to another bank robbery and another hide-out, this time at the home of relative Mattie (Louise Fletcher - in her first feature film role.) When they leave this time, Bowie is involved in a particularly nasty traffic accident, and Chicamaw must shoot two lawmen dead to escape the scene without being apprehended. Bowie recuperates back at Mobley's place, and it's while being looked after by Keechie that the two fall in love. They get themselves a place out of the way, and find an enjoyable pace of life - but when Bowie meets Chicamaw and T-Dub again, he robs another bank again - which results in another killing. With the heat from both the law and the general population becoming intense, and with Keechie falling pregnant, the young man has to hope he's making the right decisions if he's to survive and start a family.

Joan Tewkesbury had simply been a script supervisor on McCabe & Mrs. Miller when she was suddenly conscripted into the Altman filmmaking machine and asked to play a small role in the film. Now she was being asked by him to adapt Edward Anderson's 1937 novel and Altman's faith in her paid off - he was pleased enough with what she'd done that instead of continuing on his freewheeling ways, he'd stick to the script and story - while still allowing the actors to improvise lines in the context of individual scenes. It would be one of the first screenplays he'd not throw in the trash can - and when production on Thieves Like Us started Altman sent Tewkesbury to Nashville to investigate the country music scene up there for a film he was intending to make. In the end, Nashville (1975) would be based on her diary and experiences there. You can sense that Altman's instinctive intuition with Tewkesbury was right on the money, and although both Calder Willingham and Robert Altman would be given screenwriting credits, this is her movie. It was only after production had started that Altman would find out that the book had been adapted once already, as They Live by Night in 1948.

On this film, once again, he'd have his stable of regular performers comfortably playing their part, and helping to bring their characters alive - you can sense the depth they have, as if they're real living people. Keith Carradine, of the famous Carradine acting family, had debuted in McCabe & Mrs. Miller. John Schuck had been with Altman a while, and featured in M*A*S*H, Brewster McCloud and McCabe & Mrs. Miller. Bert Remsen had been part of Brewster McCloud's casting department when he was conscripted as an actor on the film - played his scene brilliantly, and found himself appearing in McCabe & Mrs. Miller before this. Shelley Duvall had been discovered by Altman in Texas and was introduced in Brewster McCloud to great effect. She also had a part in McCabe & Mrs. Miller - touchingly, also opposite the young Keith Carradine, making this a kind of sweet reunion for the two lovestruck characters. Tom Skerritt had appeared in M*A*S*H. The comfort and familiarity he had with his actors makes Altman's films as warm as they are. Louise Fletcher is fantastic in her role as well, and is very well cast as a prim, proper and strict housewife having to contend with a family that's either in prison or causing her trouble.

There had been a change in director of photography - French cinematographer Jean Boffety was behind the lens after a series of films Altman had done with Vilmos Zsigmond. It's my opinion that Boffety probably should have been given an Oscar nomination for the cinematography he's done on Thieves Like Us - it's such a visually lush film, full of the green topography of Mississippi and he captures this in many different ways from different perspectives. He also follows the lead of his director by shooting many scenes through windows and flywire - and past obstructions, giving us that voyeur's view and sense of diffusion. Of course, it wouldn't be an Altman film without the occasionally delightful zoom in or zoom out - now a kind of calling card that's instantly recognizable. Every shot - lengthy or short, long or close-up, is framed beautifully, and just looks extraordinarily good. I love the look Thieves Like Us has - aided by filming on location and not on sets. Boffety, not being from the U.S., felt compelled to take on the challenge of filming in Mississippi - a place most cinematographers like to avoid. The landscapes, tracking and dolly shots (including a wonderful, high-speed, road shot that was only possible because a new road had just been created parallel to an old one) all take on a note of perfection.

There's no score to the film - instead we get a consistent dose of 1936/7 radio as a background to everything that goes on in the film. It works really well, and aside from the music which helps to ground us in this place, time and circumstance there are many serials which involve crime and crime fighters, painting a picture of the national mood as far as gangsters and criminal activity is concerned. When Bowie and Keechie first start making love we get a radio adaptation of Romeo and Juliet that repeats as much as their lovemaking repeats. All wonderfully inventive and done with a filmmakers instinct that had no peer at the time. Thieves Like Us is a great film that was hardly promoted or noticed on release - and it's one that has yet to be properly discovered. You hear a collection of old songs and tunes, from the likes of Johnny Mercer, Victor Herbert, Irving Mills and Lew Brown. We simply roll along with our characters as the radio is on in the background, and it feels natural - but it's expertly guided and purposely arranged to fit the mood and circumstance of each moment.

The first time I watched Thieves Like Us it took me by surprise - I was expecting to see something more fringe from such a low-budget 1970s feature, but this has the feel of classic - a top of the line, wonderfully acted, beautifully captured film that is a pleasure to watch. The way the characters slowly change, from an almost adolescent immature happiness into three distinct characters that all have their troubling and fateful flaws, has a perfect timing to it. The rhythm, of the story and scenes, seems perfect. It's so appealing in it's sights and sounds. The story is hard-edged, but slants towards love, kinship and friendship to such a degree murders only register fully on Bowie's face, which we read so clearly that we trust him as a kind of moral arbiter - one that is ironically also a killer. There's no pretension - the film is made up of perfectly normal day-to-day moments of the innocuous which add up to something greater, and these moments are only briefly interrupted by events of more magnitude - and even the bigger moments play as everyday. It feels like the most honest, realistic and personal of depression-era crime thrillers.

Now, there's a product which dominates this film - Coca-Cola. The characters seem obsessed with it, and Coca-Cola advertisements are everywhere. There's even a Coca-Cola wagon that creeps along a street with a giant bottle of Coke in the back - and there are empty bottles of Coke, or else the characters are drinking Coke, in every scene. Emanuel Levy wrote that this represented an "icon of popular culture" and that Coke was "one of the few unifying objects in an increasingly diversified society" - that people of all classes could afford to drink it. He also said that this was "only a superficial equality" and functioned as a kind of "opium to the masses" - distracting them from the turmoil of depression era life in the 30s. He connects it to the superficial camaraderie the main characters have - and that becomes clearer as the film goes on and the characters solidify into three distinct people under pressure. However it's interpreted, it's one part of Thieves Like Us that stands out as interpretive and obviously being there for a reason. The story by itself is good enough to be entertaining, but there's that little iconography in the foreground of the film as an added bonus - one that could easily be misinterpreted as product placement, although a little too extreme even for that.

In the end it's another film which attains greatness in this 1970s Altman period - and while McCabe & Mrs. Miller has since received it's due, Thieves Like Us has continued to lurk in the background, remaining a film most people haven't seen. Bank robberies, the depression, guns and of course early 20th Century cars (usually with bullet holes) represent a newfound fascination with an era of crime that was unique to this time period - and I'd say that Thieves Like Us is my favourite film pertaining to this style and subject. It brings with it that Altman sense of grounded reality and applies it to subjects that were often mythologised. In through this walk the likes of Shelley Duvall, with her haunting eyes but jaunty tone, and the young fresh-faced Keith Carradine - all boyish charm and innocence despite having already shot someone to death before escaping prison. I've never seen the likes of characters such as these. Topping it off is how beautiful Mississippi looks in it's green resplendence, and how distinct American culture was as captured by a new national obsession - the radio. It makes for a film that should really have been a big hit - but it seems that this particular director confounded those operating the conveyer belt of cookie-cutter movies that were the opium of the masses back then. It deserves it's reconsideration.