← Back to Reviews

in

Those who have had the misfortune of interacting with me on the internet for at least a few years know that one of my more questionable movie opinions pertains to the famous fight scene in They Live. Namely, that I think it kind of sucks. More specifically, that it's shapeless, repetitive, and goes on for far too long and well past the point of whatever the punchline is supposed to be. And with some regularity, I would trot this one out, like someone who's bad at holding their liquor when they've had a few too many drinks and wants to let you know what they really think, only in this case it's about They Live or The Passion of Joan of Arc or Juliette Binoche (don't ask). And no matter how much others would spar with me or try to get me to look at it the right away, I would refuse to relent, not entirely unlike Keith David's character. Well, that's what I used to think, and I can sheepishly report with this latest rewatch that I know think the fight scene is great, and I laughed all the way through. Yes, yes, everybody else was right, the length is the point, but I think there's a certain understated pinball quality to the way Carpenter shoots and cuts the scene, finding a certain dynamism and maybe even grace to what in lesser hands would be merely a shambling, ungainly brawl. Nobody's right all the time.

As for the rest of the movie, I was right the whole time, as it held up splendidly. For a movie that's established in the pop culture lexicon in an almost memefied state, it is nice to be reacquainted with how steadily it escalates. If one were to graph this movie, you could depict it with a straight line rising at a forty-five degree angle. In the opening the hero starts off with nothing, slowly picks up clues that all is not right with the world, slides into the resistance and by the end is ready to overthrow the system. You could even liken it to video games (a medium that Carpenter is a great fan of), particularly with the Grand Theft Auto style killing spree the hero goes on, only to lose a life so to speak and end up having to recruit a friendly who joins him for the final mission. Imagine if Lance Vance was actually helpful and didn't need his ass saved every time, and you get Keith David.

In that sense, the movie resists being read as an endorsement of conspiracy-minded thinking (and Carpenter has condemned the embracing of the film by hate groups who misread the film as a racist metaphor), in that none of those chowderheads would be as capable or cool as Roddy Piper, despite whatever delusions they might have about themselves. The casting of Piper is key to the movie's success, in that he not only comes off credibly as working class, but has a certain physicality and reactive quality that help him serve as an effective audience vantage point and sell the sense of escalation. He has some of the same effect as a young Sylvester Stallone, who at this time had begun to resemble a live action cartoon, and this movie serves as a nice left-wing counterpoint to the jingoism of the Rambo sequels and other action movies of the era, with a bit of '50s sci-fi paranoia sprinkled in for good measure.

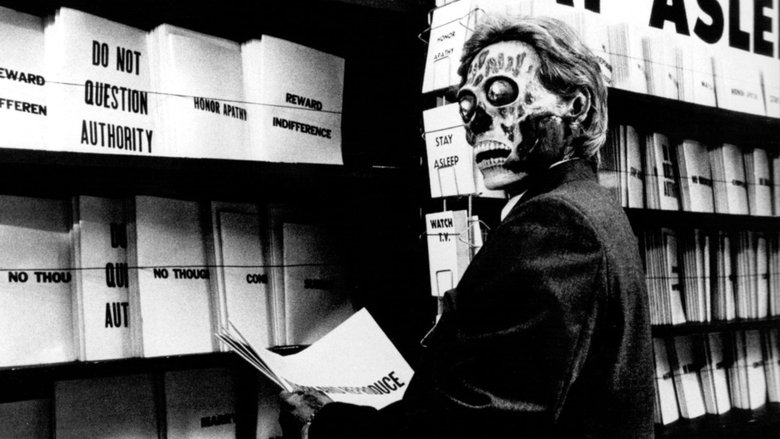

But of course, merely having politics does not by itself a good movie make, and what I think makes this one great is the way Carpenter marries this material to a muscular visual style. You can see how he paints the shantytown and its destruction with an almost apocalyptic quality, and the sinister contrasts he draws between this setting and the skyscrapers that tower over it, or the ominous images of the subtly militaristic police presence, all of which primes you for the leap into paranoid fantasy. We can already feel that the world of this movie is dystopic, how surprising is it that it's run by evil aliens surveilling us with little flying saucers? And the forcefulness of the images makes the action that much more cathartic. Sure, in real life, it's easy to feel powerless in the face of great economic inequality, but in Carpenter's world, we can do something about it.

They Live (Carpenter, 1988)

Those who have had the misfortune of interacting with me on the internet for at least a few years know that one of my more questionable movie opinions pertains to the famous fight scene in They Live. Namely, that I think it kind of sucks. More specifically, that it's shapeless, repetitive, and goes on for far too long and well past the point of whatever the punchline is supposed to be. And with some regularity, I would trot this one out, like someone who's bad at holding their liquor when they've had a few too many drinks and wants to let you know what they really think, only in this case it's about They Live or The Passion of Joan of Arc or Juliette Binoche (don't ask). And no matter how much others would spar with me or try to get me to look at it the right away, I would refuse to relent, not entirely unlike Keith David's character. Well, that's what I used to think, and I can sheepishly report with this latest rewatch that I know think the fight scene is great, and I laughed all the way through. Yes, yes, everybody else was right, the length is the point, but I think there's a certain understated pinball quality to the way Carpenter shoots and cuts the scene, finding a certain dynamism and maybe even grace to what in lesser hands would be merely a shambling, ungainly brawl. Nobody's right all the time.

As for the rest of the movie, I was right the whole time, as it held up splendidly. For a movie that's established in the pop culture lexicon in an almost memefied state, it is nice to be reacquainted with how steadily it escalates. If one were to graph this movie, you could depict it with a straight line rising at a forty-five degree angle. In the opening the hero starts off with nothing, slowly picks up clues that all is not right with the world, slides into the resistance and by the end is ready to overthrow the system. You could even liken it to video games (a medium that Carpenter is a great fan of), particularly with the Grand Theft Auto style killing spree the hero goes on, only to lose a life so to speak and end up having to recruit a friendly who joins him for the final mission. Imagine if Lance Vance was actually helpful and didn't need his ass saved every time, and you get Keith David.

In that sense, the movie resists being read as an endorsement of conspiracy-minded thinking (and Carpenter has condemned the embracing of the film by hate groups who misread the film as a racist metaphor), in that none of those chowderheads would be as capable or cool as Roddy Piper, despite whatever delusions they might have about themselves. The casting of Piper is key to the movie's success, in that he not only comes off credibly as working class, but has a certain physicality and reactive quality that help him serve as an effective audience vantage point and sell the sense of escalation. He has some of the same effect as a young Sylvester Stallone, who at this time had begun to resemble a live action cartoon, and this movie serves as a nice left-wing counterpoint to the jingoism of the Rambo sequels and other action movies of the era, with a bit of '50s sci-fi paranoia sprinkled in for good measure.

But of course, merely having politics does not by itself a good movie make, and what I think makes this one great is the way Carpenter marries this material to a muscular visual style. You can see how he paints the shantytown and its destruction with an almost apocalyptic quality, and the sinister contrasts he draws between this setting and the skyscrapers that tower over it, or the ominous images of the subtly militaristic police presence, all of which primes you for the leap into paranoid fantasy. We can already feel that the world of this movie is dystopic, how surprising is it that it's run by evil aliens surveilling us with little flying saucers? And the forcefulness of the images makes the action that much more cathartic. Sure, in real life, it's easy to feel powerless in the face of great economic inequality, but in Carpenter's world, we can do something about it.