← Back to Reviews

in

Bogarts mouth may have mostly been filled with smoke and marbles, but poetry was in there too. You might hardly think it belonged in such a place. And maybe it would have preferred to keep itself inside, away from the mean streets he lived in. But the brute force of his New York drawl would always eventually drag it out. By the hair. Slightly slurred and stepped on. But always a perfect morsel of words, shimmering like a pothole full of blood. Like rain gently soaking a greasy, old fedora.

No matter how hard-edged the genre of Film Noir sometimes appears to be, one of its most beautiful contradictions is its relationship with language, and the uneasy elegance it brings to its cynicism. Without it, its reliance on fists and bullets and betrayals would never dance. But with it, it becomes a perfectly composed world of uncertainties. It allows its characters to vividly articulate every contour of the moral wasteland that surrounds them. Then, if you allow them a few more puffs on their cigarette, they’ll tell you all about the many ways it has warped them. It doesn’t matter how slow the articulation of some lumbering henchman might be. Or how wet and dripping the appeals for mercy become upon the lips of some rat-faced toady. Even when seemingly inarticulate, the characters in Noir speak in images and allusions and insults that are all the streetlight one needs to make out the shape of their souls.

And then they’ll sock you with a fist.

In the best examples of the genre, the effect is a miraculous balance between the artificial and the naturalistic. It is writing of the most thoughtful contemplation, eventually tumbling from the mouths of characters who only have enough time to spit these words out along with their teeth. As a result, it takes an almost perfect touch to make it work, or else it could easily go wrong. Maybe it would be a case of too much poetry. Or not enough grit. It’s a tricky mixture. Noir is a concoction that needs just the right proportions before its spilled over the rocks. It can dilute real easy. But has a necessary cheapness that forbids us from ever drinking it straight.

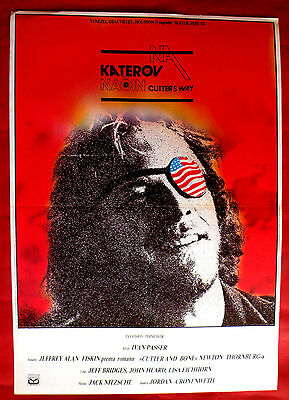

And this will very much be the highwire act that Cutter’s Way attempts in the streets of 1980’s Santa Barbara, and it’s hard to say if it entirely succeeds on these merits alone. The grit is always either too much or too little. It will fluctuate between an overkill of gruesomness that dumps semen crusted bodies in trashcans one minute. Then, before that queasiness subsides, a character arrives wearing a costume shop eye patch, and there is a sense that maybe all these sticky evils are being presented to us from the game book of some murder/dinner party.

As for the poetry, it has already been pre-fed to the actors, and they seem to have stored an abundance of it in the pockets of their cheeks. Their faces absolutely bulge with it. And when it is spoken, their endless turns of phrase will sound thick with edits and notes scribbled all around the margins. If it illuminates anyone's soul, it is mostly that of the screenwriters, which will appear as a less than enthralling silhouette hunched over a typewriter, pulling at their hair, desperately thumbing through some dog-eared Dashiell Hammet paperback. And, ultimately, the fruit of its labors will be suspect. We ask for characters, and we get a tangle of ten-dollar words. And when we ask for poetry, the hat Cutter’s Way throws into the ring is already damp from memories of better scripts.

But somehow these unbalanced ingredients become a necessity when we begin to recognize how unrepentantly cynical a film this is. There is an inflexibility to the direction its narrative takes, forcing its audience to follow the assurances of its alcoholic and paranoid characters that we are on the road towards some kind of street justice. And at the end of this road, there will in fact be a villain, even though Cord (the stone-faced oil magnate we occasionally will see lurking in the background) is a character we hardly have any real stakes in. We are unsure what he is actually responsible for. And we can’t be sure exactly why we are meant to fear and despise him At least not beyond the increasingly frenzied conspiracies touted by the film’s titular character, a disabled and extremely disturbed Vietnam veteran played by John Heard.

Without these ganglier elements, the sometimes overripe dialogue and the tonal shifts which make us continually feel we are standing on some kind of fault line between the despairing and the absurd, Cutter’s Way might just feel like a third-rate Chinatown. But with its many imperfections in full view, somehow, maybe even by mistake, it gives the film an almost B Movie viscerality. The kind of clenched fist we might expect shooting out at us from a Samuel Fuller film, even as we contemplate the morose vibe it seems to have lifted from Arthur Penn’s “Night Moves”.

Because of all this, it’s possible Cutter’s Way is forcing me to re-evaluate the essentials I once thought to be so necessary. Maybe, in fact, its slight variation on Noirs fundamental elements is exactly right coming after the age of American grindhouse and exploitation films. Maybe for us to truly embrace the loner in such a society, what we need instead is something a little crass and occasionally even silly. It’s possible grit and poetry simply don’t cut it anymore. At least not when basked in the neon glow of 1980’s Santa Barbara. This kind of place requires something a little meaner. And dumber.

No matter how hard-edged the genre of Film Noir sometimes appears to be, one of its most beautiful contradictions is its relationship with language, and the uneasy elegance it brings to its cynicism. Without it, its reliance on fists and bullets and betrayals would never dance. But with it, it becomes a perfectly composed world of uncertainties. It allows its characters to vividly articulate every contour of the moral wasteland that surrounds them. Then, if you allow them a few more puffs on their cigarette, they’ll tell you all about the many ways it has warped them. It doesn’t matter how slow the articulation of some lumbering henchman might be. Or how wet and dripping the appeals for mercy become upon the lips of some rat-faced toady. Even when seemingly inarticulate, the characters in Noir speak in images and allusions and insults that are all the streetlight one needs to make out the shape of their souls.

And then they’ll sock you with a fist.

In the best examples of the genre, the effect is a miraculous balance between the artificial and the naturalistic. It is writing of the most thoughtful contemplation, eventually tumbling from the mouths of characters who only have enough time to spit these words out along with their teeth. As a result, it takes an almost perfect touch to make it work, or else it could easily go wrong. Maybe it would be a case of too much poetry. Or not enough grit. It’s a tricky mixture. Noir is a concoction that needs just the right proportions before its spilled over the rocks. It can dilute real easy. But has a necessary cheapness that forbids us from ever drinking it straight.

And this will very much be the highwire act that Cutter’s Way attempts in the streets of 1980’s Santa Barbara, and it’s hard to say if it entirely succeeds on these merits alone. The grit is always either too much or too little. It will fluctuate between an overkill of gruesomness that dumps semen crusted bodies in trashcans one minute. Then, before that queasiness subsides, a character arrives wearing a costume shop eye patch, and there is a sense that maybe all these sticky evils are being presented to us from the game book of some murder/dinner party.

As for the poetry, it has already been pre-fed to the actors, and they seem to have stored an abundance of it in the pockets of their cheeks. Their faces absolutely bulge with it. And when it is spoken, their endless turns of phrase will sound thick with edits and notes scribbled all around the margins. If it illuminates anyone's soul, it is mostly that of the screenwriters, which will appear as a less than enthralling silhouette hunched over a typewriter, pulling at their hair, desperately thumbing through some dog-eared Dashiell Hammet paperback. And, ultimately, the fruit of its labors will be suspect. We ask for characters, and we get a tangle of ten-dollar words. And when we ask for poetry, the hat Cutter’s Way throws into the ring is already damp from memories of better scripts.

But somehow these unbalanced ingredients become a necessity when we begin to recognize how unrepentantly cynical a film this is. There is an inflexibility to the direction its narrative takes, forcing its audience to follow the assurances of its alcoholic and paranoid characters that we are on the road towards some kind of street justice. And at the end of this road, there will in fact be a villain, even though Cord (the stone-faced oil magnate we occasionally will see lurking in the background) is a character we hardly have any real stakes in. We are unsure what he is actually responsible for. And we can’t be sure exactly why we are meant to fear and despise him At least not beyond the increasingly frenzied conspiracies touted by the film’s titular character, a disabled and extremely disturbed Vietnam veteran played by John Heard.

Without these ganglier elements, the sometimes overripe dialogue and the tonal shifts which make us continually feel we are standing on some kind of fault line between the despairing and the absurd, Cutter’s Way might just feel like a third-rate Chinatown. But with its many imperfections in full view, somehow, maybe even by mistake, it gives the film an almost B Movie viscerality. The kind of clenched fist we might expect shooting out at us from a Samuel Fuller film, even as we contemplate the morose vibe it seems to have lifted from Arthur Penn’s “Night Moves”.

Because of all this, it’s possible Cutter’s Way is forcing me to re-evaluate the essentials I once thought to be so necessary. Maybe, in fact, its slight variation on Noirs fundamental elements is exactly right coming after the age of American grindhouse and exploitation films. Maybe for us to truly embrace the loner in such a society, what we need instead is something a little crass and occasionally even silly. It’s possible grit and poetry simply don’t cut it anymore. At least not when basked in the neon glow of 1980’s Santa Barbara. This kind of place requires something a little meaner. And dumber.