← Back to Reviews

in

Greed

(Erich von Stroheim, 1924)

(Starring: Gibson Gowland; ZaSu Pitts; Jean Hersholt)

"I intended to show men and women as they are all over the world, none of them perfect, with their good and bad qualities, their noble and idealistic sides and their jealous, vicious, mean and greedy sides. I was not going to compromise."

--- Erich von Stroheim

Many modern filmmakers ignore the "picture" part of motion pictures, instead relying on lazy voice-over narrations and on-the-nose dialogue that tells the audience everything they need to know about the plot and the characters instead of showing them. But in 1924, long before directors had dialogue or special-effects or voice-over narrations in their toolbox, a movie had to rely solely on imagery to convey its stories to the audience. Sure, there were occasional placards to explain a transition or a character's background or an important line of speech, as well an accompanying musical score to match the emotions on screen, but everything else had to be accomplished through a visual palette of imagery and symbolism and metaphor.

As Norma Desmond says in Sunset Boulevard, "We didn't need dialogue. We had faces!" And it's those wonderfully expressive, emotive faces from the silent era that served as a character's canvas. Actors and actresses--- such as Gibson Gowland and ZaSu Pitts in Greed--- embodied their roles, using only their faces and their bodies to convey the inner-workings of their characters. And directors like Erich von Stroheim (who, coincidentally, played Norma Desmond's butler in the aforementioned Sunset Boulevard) had to inject meaning, subtext and depth into every scene if they were going to maximize the potential of their visual medium. This is why Greed, despite being ninety-years-old(!), remains one of the most powerful and masterful works of cinema that I've ever seen.

Greed illustrates that no matter how hard we chase success, we are ultimately slaves to fate and circumstance. And no matter how hard we strive to do good, to be reliable and to be morally upright, our animalistic urges and our basest desires occasionally get in the way, corrupting our minds in a moment of passion and causing us to do things that we later regret. The characters in Greed are flawed, but normal. Eventually, however, an unkind twist of fate, along with an unforgiving environment and the "demons" in their blood, ultimately take their toll. Each character becomes infected with a cancer of the soul--- symbolized by the color gold (which was hand-colored onto certain scenes, allowing the golden glow to radiate from the black-and-white surroundings like a poisonous toxin)--- and their downward spiral begins.

We are introduced to McTeague, the main character, as he takes a break from mining to pick up a small, injured bird. He nuzzles the bird against his face and kisses it on the head, then another miner slaps the bird out of McTeague's hand. In an act of brute strength, McTeague, consumed with rage, lifts the man over his head and throws him off the bridge. In later scenes, when we see the caged canaries that McTeague keeps as pets, the birds serve as a reminder of McTeague's conflicted nature: his compassion, which we learn he inherited from his mother, as well as his violent temper, which he inherited from his father. It is an internal tug-of-war that wages inside of his character for the duration of the movie, until one side eventually triumphs.

During the wedding sequence, in an example of the multi-layered depth that director Erich von Stroheim adds to every scene, we see through the window a funeral procession that is taking place outside on the street below. Many viewers might not notice such a detail, since the camera doesn't focus on the funeral procession or draw attention to it, but for observant viewers the funeral procession gives the wedding sequence an ominous tone, signifying the eventual demise of our bride and groom. When Trina, McTeague's wife, wins the lottery shortly afterwards, she slowly changes from a meek, wide-eyed woman to a lying, conniving, mean-spirited wench, hoarding her winnings despite the couple's eventual struggles. Her gradual deterioration, both physically and mentally, is startling, and it is a testament to ZaSu Pitts's phenomenal performance. The change in Marcus Schouler, however, McTeague's friend and Trina's cousin, is less a transformation than a revelation, as his overwhelming jealousy and hatred unveil his true persona. During his supposed "farewell," when the camera cuts to a cat in the room flicking its tail in agitation, and then later shows the same cat attack the pet canaries just before McTeague receives bad news, we don't need to be told who has reported McTeague's unlicensed dental practice to know that Marcus is responsible.

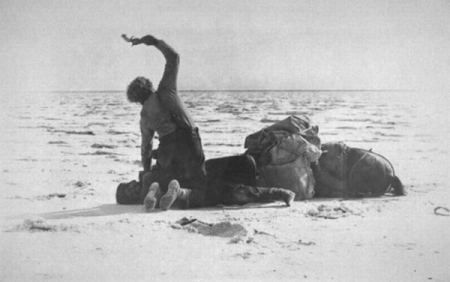

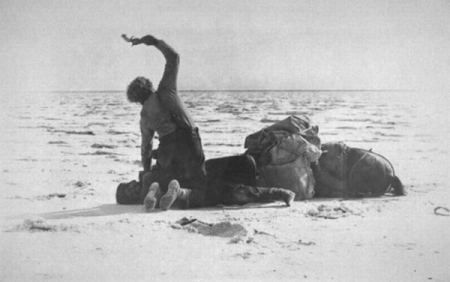

There is nothing Hollywood about Greed, no happy endings or easy answers or saccharine manipulations, which is probably why it was so poorly received by the public upon its release in 1924. Greed is unafraid of exploring the ugly depths of humanity. When McTeague and Marcus wander into the desert---- which von Stroheim filmed on location in the harsh, unforgiving conditions of Death Valley, resulting in numerous crew members being hospitalized for heat exhaustion--- the bleak landscape, with its parched earth and searing sun, is symbolic of how far our characters have fallen. They've lost everything, tangible and intangible, and their souls lay barren and exposed. It is a powerful, uncompromising ending to a powerful, uncompromising film. Not only has Greed surpassed Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans as the best film I've seen from the silent era, it can proudly stand alongside the greatest films of all-time. Greed is, simply put, a masterpiece.

(Erich von Stroheim, 1924)

(Starring: Gibson Gowland; ZaSu Pitts; Jean Hersholt)

"I intended to show men and women as they are all over the world, none of them perfect, with their good and bad qualities, their noble and idealistic sides and their jealous, vicious, mean and greedy sides. I was not going to compromise."

--- Erich von Stroheim

Many modern filmmakers ignore the "picture" part of motion pictures, instead relying on lazy voice-over narrations and on-the-nose dialogue that tells the audience everything they need to know about the plot and the characters instead of showing them. But in 1924, long before directors had dialogue or special-effects or voice-over narrations in their toolbox, a movie had to rely solely on imagery to convey its stories to the audience. Sure, there were occasional placards to explain a transition or a character's background or an important line of speech, as well an accompanying musical score to match the emotions on screen, but everything else had to be accomplished through a visual palette of imagery and symbolism and metaphor.

As Norma Desmond says in Sunset Boulevard, "We didn't need dialogue. We had faces!" And it's those wonderfully expressive, emotive faces from the silent era that served as a character's canvas. Actors and actresses--- such as Gibson Gowland and ZaSu Pitts in Greed--- embodied their roles, using only their faces and their bodies to convey the inner-workings of their characters. And directors like Erich von Stroheim (who, coincidentally, played Norma Desmond's butler in the aforementioned Sunset Boulevard) had to inject meaning, subtext and depth into every scene if they were going to maximize the potential of their visual medium. This is why Greed, despite being ninety-years-old(!), remains one of the most powerful and masterful works of cinema that I've ever seen.

Greed illustrates that no matter how hard we chase success, we are ultimately slaves to fate and circumstance. And no matter how hard we strive to do good, to be reliable and to be morally upright, our animalistic urges and our basest desires occasionally get in the way, corrupting our minds in a moment of passion and causing us to do things that we later regret. The characters in Greed are flawed, but normal. Eventually, however, an unkind twist of fate, along with an unforgiving environment and the "demons" in their blood, ultimately take their toll. Each character becomes infected with a cancer of the soul--- symbolized by the color gold (which was hand-colored onto certain scenes, allowing the golden glow to radiate from the black-and-white surroundings like a poisonous toxin)--- and their downward spiral begins.

We are introduced to McTeague, the main character, as he takes a break from mining to pick up a small, injured bird. He nuzzles the bird against his face and kisses it on the head, then another miner slaps the bird out of McTeague's hand. In an act of brute strength, McTeague, consumed with rage, lifts the man over his head and throws him off the bridge. In later scenes, when we see the caged canaries that McTeague keeps as pets, the birds serve as a reminder of McTeague's conflicted nature: his compassion, which we learn he inherited from his mother, as well as his violent temper, which he inherited from his father. It is an internal tug-of-war that wages inside of his character for the duration of the movie, until one side eventually triumphs.

During the wedding sequence, in an example of the multi-layered depth that director Erich von Stroheim adds to every scene, we see through the window a funeral procession that is taking place outside on the street below. Many viewers might not notice such a detail, since the camera doesn't focus on the funeral procession or draw attention to it, but for observant viewers the funeral procession gives the wedding sequence an ominous tone, signifying the eventual demise of our bride and groom. When Trina, McTeague's wife, wins the lottery shortly afterwards, she slowly changes from a meek, wide-eyed woman to a lying, conniving, mean-spirited wench, hoarding her winnings despite the couple's eventual struggles. Her gradual deterioration, both physically and mentally, is startling, and it is a testament to ZaSu Pitts's phenomenal performance. The change in Marcus Schouler, however, McTeague's friend and Trina's cousin, is less a transformation than a revelation, as his overwhelming jealousy and hatred unveil his true persona. During his supposed "farewell," when the camera cuts to a cat in the room flicking its tail in agitation, and then later shows the same cat attack the pet canaries just before McTeague receives bad news, we don't need to be told who has reported McTeague's unlicensed dental practice to know that Marcus is responsible.

There is nothing Hollywood about Greed, no happy endings or easy answers or saccharine manipulations, which is probably why it was so poorly received by the public upon its release in 1924. Greed is unafraid of exploring the ugly depths of humanity. When McTeague and Marcus wander into the desert---- which von Stroheim filmed on location in the harsh, unforgiving conditions of Death Valley, resulting in numerous crew members being hospitalized for heat exhaustion--- the bleak landscape, with its parched earth and searing sun, is symbolic of how far our characters have fallen. They've lost everything, tangible and intangible, and their souls lay barren and exposed. It is a powerful, uncompromising ending to a powerful, uncompromising film. Not only has Greed surpassed Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans as the best film I've seen from the silent era, it can proudly stand alongside the greatest films of all-time. Greed is, simply put, a masterpiece.