← Back to Reviews

in

Directed by Herbert Ross

Screenplay by Dennis Potter

Cinematography by Gordon Willis

CAST: Steve Martin, Bernadette Peters, Jessica Harper,

Vernel Bagneris, John McMartin, and Christopher Walken

1981, approximately 108 minutes

In 1981, Steve Martin took an artistic risk which might have drastically changed his then-new screen image and Herbert Ross tried to reinvent the Musical for a new, post-modern sensibility. The film was Pennies from Heaven, and it was a box-office flop. A few critics sang its praises, including Pauline Kael, but by and large it was dismissed. I think it is a brilliant movie that was so far ahead of its time, and still lies mostly undiscovered.

British television writer and novelist Dennis Potter ("The Singing Detective") had a long, successful career starting in the 1960s in the UK, and one of his biggest accomplishments was the 1978 BBC mini-series "Pennies from Heaven", starring Bob Hoskins. It tells the story of a sheet-music salesman in 1930s Britain who dreams of living out the lyrics of the songs he peddles. These rich fantasies are contrasted sharply with the darkness of his real life. Potter pared down and adapted his own eight-hour teleplay into a film screenplay, shifting the setting to Depression-era Chicago, which caught the attention of Herbert Ross, who had been on quite a roll in the 1970s, helming such projects as The Goodbye Girl, The Sunshine Boys, The Last of Sheila, The Turning Point, California Suite, The Seven-Per-Cent Solution and Play it Again, Sam. Steve Martin, fresh from mega success as a stand-up comic playing to rock-and-roll-size crowds and distilling that wild and crazy persona first to the small screen on "Saturday Night Live" and his own specials, and then into The Jerk (1979), signed on to play the dark and complicated lead. Broadway star Bernadette Peters, who was Martin's co-star in The Jerk and at the time his real-life paramour, and Jessica Harper (Phantom of the Paradise, Suspiria, My Favorite Year) would co-star, with Christopher Walken in film-stealing support.

Pennies from Heaven is the musical as psychotic episode. The numbers, often elaborate set pieces, replicating the styles if not the scenes of some classic cinema Musicals, and of which Busby Berkeley himself would have been proud, are delusions that have absolutely zero to do with reality. The usual conceit of the Musical is that the song interludes further the plot and/or give voice to internal emotions of the characters. But not here. Martin's character Arthur is a bizarre and almost irredeemably amoral man, who creates a pretend morality in the music he loves and envisions. He claims, certainly to himself and by extension the audience, to be a pure romantic dreamer trying to honestly make his way in the world, but his selfish and hurtful actions tell otherwise. It's a rather brilliant concept, and to me works even better as a movie than as a TV project (though make no mistake, the BBC version is also spectacular and a must-see). Many of the film's references are to the otherworlds created by movie magic, worlds that millions flocked to during the Depression in order to delude themselves into a fantasy for part of an afternoon or evening. As Fred Astaire was floating across screens in top hat and tails, much of the audience was wondering if they could find steady work, or keep the tenuous hold on their income and possessions. So in one of Heaven's best sequences when Martin and Peters actually enter Follow the Fleet (1936), the Astaire & Rogers classic, the circle is complete, and Arthur's fantasy blends with the larger societal fantasy.

Another stylistic risk/choice the film makes, carrying over from what was done in the TV version, is to have the actors lip-synch to the existing period tracks, rather than re-record them with these actors. Obviously stage star Peters could have done just about anything they asked, vocally, but this added layer of artifice is intentional, both making some of the song choices seem that much odder and funnier, being mouthed by the protagonists, and also not pretending these fantasies are to be taken in simple genre terms, but almost as if they were being done in front of a mirror in your attic, when nobody was home to catch you.

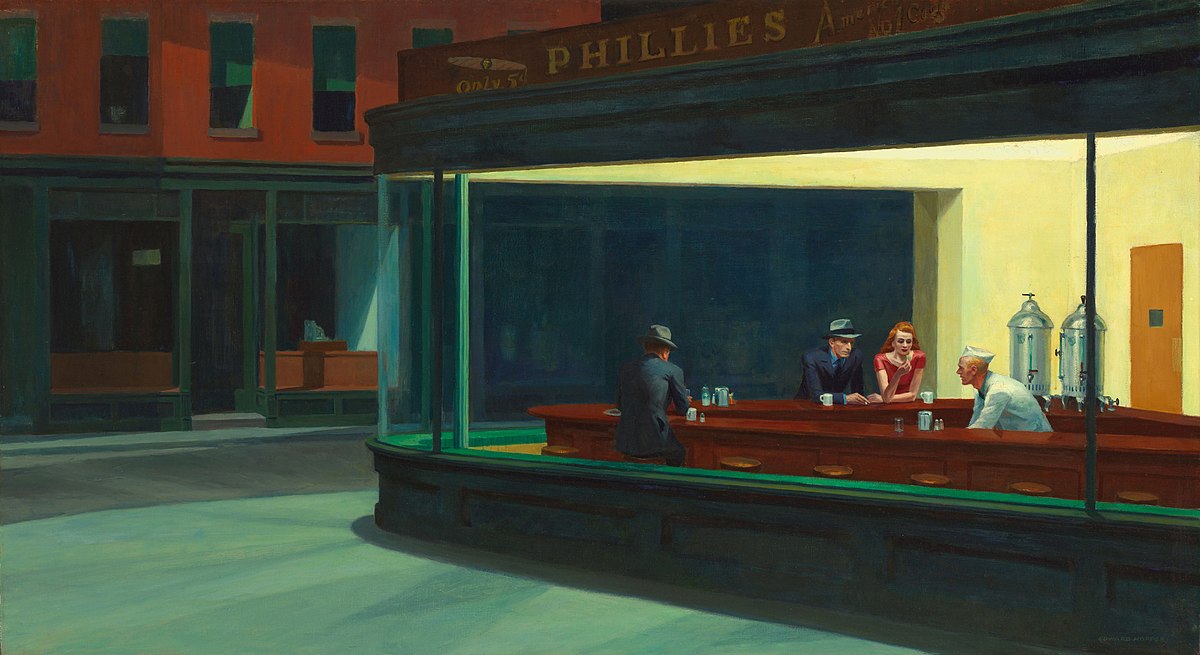

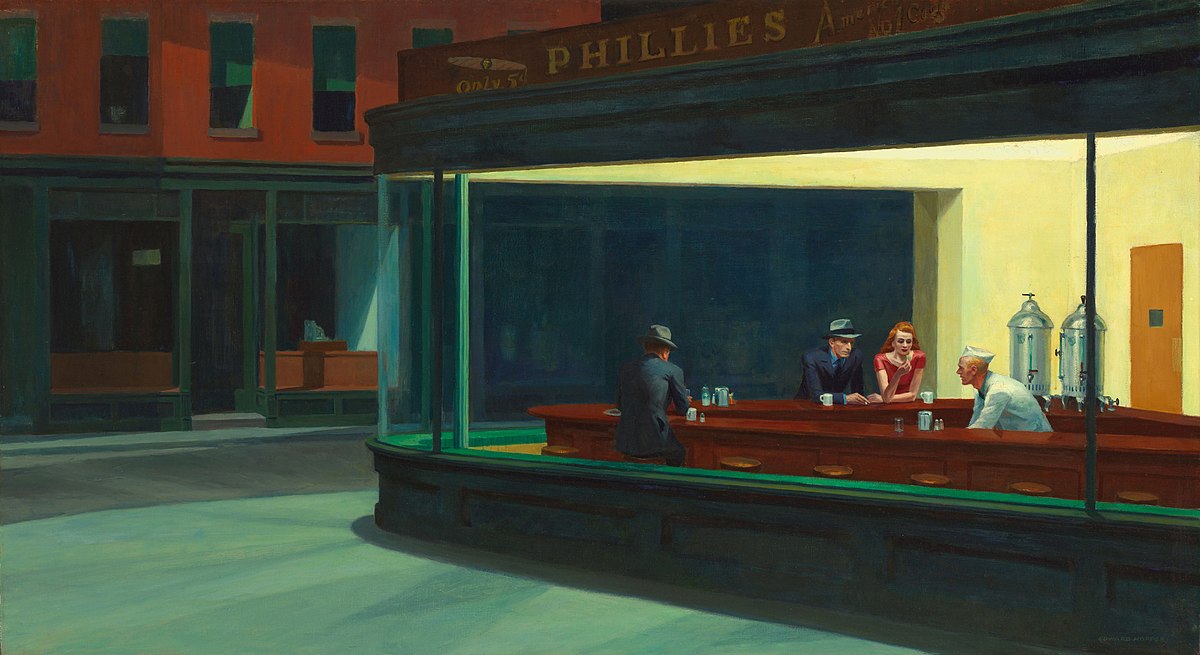

The look of the film is fantastic, with two basic palettes: the glitz of Hollywood and the dim of Edward Hopper. Several of his paintings are brought to life, including his most iconic, "Nighthawks". Gordon Willis, who was one of the most respected and imitated cinematographers of his era, having lensed The Godfather series for Coppola and Alan J. Pakula's All the President's Men before becoming Woody Allen's go-to collaborator on Annie Hall, Manhattan, Interiors, Stardust Memories, Zelig, The Purple Rose of Cairo and on and on, creates some stunning tableaus and homages.

Steve Martin has had an incredibly successful and quite diverse career in film, and while he eventually worked his way into some darker and sometimes intentionally comedy-free projects a couple decades later, it was probably too early and too bizarre a project for his fanbase to accept at the time, en masse. How might his career trajectory had changed if Pennies from Heaven wound up with multiple, high-profile Oscar nominations like Picture and Director? We'll never know.

This scene, in the next YouTube link, is a perfect example of what the film does. Christopher Walken only has one scene, really. At a particularly low point for the Peters character, she wanders into a bar on the bad side of town. The resident pimp, Walken, approaches her, buys her a drink, and offers her a job, on her back. It is tense and frightening, a cruel fate for this character who did nothing but trust the wrong man. And then, right when things look bleakest, Walken breaks into the Cole Porter tune "Let's Misbehave" by Irving Aaronson and His Commanders...

Dark and ironic eye-candy, this is Herbert Ross' masterpiece in my book, waiting to be rediscovered.

Directed by Herbert Ross

Screenplay by Dennis Potter

Cinematography by Gordon Willis

CAST: Steve Martin, Bernadette Peters, Jessica Harper,

Vernel Bagneris, John McMartin, and Christopher Walken

1981, approximately 108 minutes

In 1981, Steve Martin took an artistic risk which might have drastically changed his then-new screen image and Herbert Ross tried to reinvent the Musical for a new, post-modern sensibility. The film was Pennies from Heaven, and it was a box-office flop. A few critics sang its praises, including Pauline Kael, but by and large it was dismissed. I think it is a brilliant movie that was so far ahead of its time, and still lies mostly undiscovered.

British television writer and novelist Dennis Potter ("The Singing Detective") had a long, successful career starting in the 1960s in the UK, and one of his biggest accomplishments was the 1978 BBC mini-series "Pennies from Heaven", starring Bob Hoskins. It tells the story of a sheet-music salesman in 1930s Britain who dreams of living out the lyrics of the songs he peddles. These rich fantasies are contrasted sharply with the darkness of his real life. Potter pared down and adapted his own eight-hour teleplay into a film screenplay, shifting the setting to Depression-era Chicago, which caught the attention of Herbert Ross, who had been on quite a roll in the 1970s, helming such projects as The Goodbye Girl, The Sunshine Boys, The Last of Sheila, The Turning Point, California Suite, The Seven-Per-Cent Solution and Play it Again, Sam. Steve Martin, fresh from mega success as a stand-up comic playing to rock-and-roll-size crowds and distilling that wild and crazy persona first to the small screen on "Saturday Night Live" and his own specials, and then into The Jerk (1979), signed on to play the dark and complicated lead. Broadway star Bernadette Peters, who was Martin's co-star in The Jerk and at the time his real-life paramour, and Jessica Harper (Phantom of the Paradise, Suspiria, My Favorite Year) would co-star, with Christopher Walken in film-stealing support.

Pennies from Heaven is the musical as psychotic episode. The numbers, often elaborate set pieces, replicating the styles if not the scenes of some classic cinema Musicals, and of which Busby Berkeley himself would have been proud, are delusions that have absolutely zero to do with reality. The usual conceit of the Musical is that the song interludes further the plot and/or give voice to internal emotions of the characters. But not here. Martin's character Arthur is a bizarre and almost irredeemably amoral man, who creates a pretend morality in the music he loves and envisions. He claims, certainly to himself and by extension the audience, to be a pure romantic dreamer trying to honestly make his way in the world, but his selfish and hurtful actions tell otherwise. It's a rather brilliant concept, and to me works even better as a movie than as a TV project (though make no mistake, the BBC version is also spectacular and a must-see). Many of the film's references are to the otherworlds created by movie magic, worlds that millions flocked to during the Depression in order to delude themselves into a fantasy for part of an afternoon or evening. As Fred Astaire was floating across screens in top hat and tails, much of the audience was wondering if they could find steady work, or keep the tenuous hold on their income and possessions. So in one of Heaven's best sequences when Martin and Peters actually enter Follow the Fleet (1936), the Astaire & Rogers classic, the circle is complete, and Arthur's fantasy blends with the larger societal fantasy.

Another stylistic risk/choice the film makes, carrying over from what was done in the TV version, is to have the actors lip-synch to the existing period tracks, rather than re-record them with these actors. Obviously stage star Peters could have done just about anything they asked, vocally, but this added layer of artifice is intentional, both making some of the song choices seem that much odder and funnier, being mouthed by the protagonists, and also not pretending these fantasies are to be taken in simple genre terms, but almost as if they were being done in front of a mirror in your attic, when nobody was home to catch you.

The look of the film is fantastic, with two basic palettes: the glitz of Hollywood and the dim of Edward Hopper. Several of his paintings are brought to life, including his most iconic, "Nighthawks". Gordon Willis, who was one of the most respected and imitated cinematographers of his era, having lensed The Godfather series for Coppola and Alan J. Pakula's All the President's Men before becoming Woody Allen's go-to collaborator on Annie Hall, Manhattan, Interiors, Stardust Memories, Zelig, The Purple Rose of Cairo and on and on, creates some stunning tableaus and homages.

Steve Martin has had an incredibly successful and quite diverse career in film, and while he eventually worked his way into some darker and sometimes intentionally comedy-free projects a couple decades later, it was probably too early and too bizarre a project for his fanbase to accept at the time, en masse. How might his career trajectory had changed if Pennies from Heaven wound up with multiple, high-profile Oscar nominations like Picture and Director? We'll never know.

This scene, in the next YouTube link, is a perfect example of what the film does. Christopher Walken only has one scene, really. At a particularly low point for the Peters character, she wanders into a bar on the bad side of town. The resident pimp, Walken, approaches her, buys her a drink, and offers her a job, on her back. It is tense and frightening, a cruel fate for this character who did nothing but trust the wrong man. And then, right when things look bleakest, Walken breaks into the Cole Porter tune "Let's Misbehave" by Irving Aaronson and His Commanders...

Dark and ironic eye-candy, this is Herbert Ross' masterpiece in my book, waiting to be rediscovered.