← Back to Reviews

in

Oh man, this documentary is made of so much win, I feared my heart would swell to the point of bursting.

I went into this film thinking I was going to see a study on how a chimp can be taken out of its own environment, brought into ours and proven to understand and accomplish real communication with a human being... and I did. Sort of. However, the overall consensus seems to say a lot more about people than it does about animals. For those of you who have ever watched James Marsh's previous documentary (Man on Wire), then you're probably already familiar with the style in which he craftily tells a story. Project Nim is wonderful for its heart and soul, but also brutal in the way it really exposes human nature.

Specifically, Nim was a chimpanzee who was the subject of scientific studies to do with animal language due to their DNA being identical to a humans to a crazy degree (98% or thereabouts). Herbert Terrace, the head of the study, wanted to challenge Chomsky's thesis that "only humans have language" by raising Nim in a human family treated like a child. Two weeks after he was born, he was separated from his mother, Carolyn, and put into the hands of a young couple with several young children of their own. The year was 1973. Funnily enough, the family who initially adopted Nim didn't really seem to take the study too seriously. The LaFarge's were sort of your typical liberal, hippy family of the mid-1970's, and Stephanie (Nim's "mom") wasn't very keen on keeping charts or notes or journals on Nim's progress. Therefore, there's lots of uber cute footage of little Nim running wild through the house, being curious and insanely lovable to the LeFarge's, but not a lot of "depth" beyond that. She didn't want to treat him like an experiment; it was pretty much like having another baby for her. She was excited to show Nim the world, but not to restrain him in any way. In fact, she wasn't even keen on teaching him language because she thought it would make him less unique.

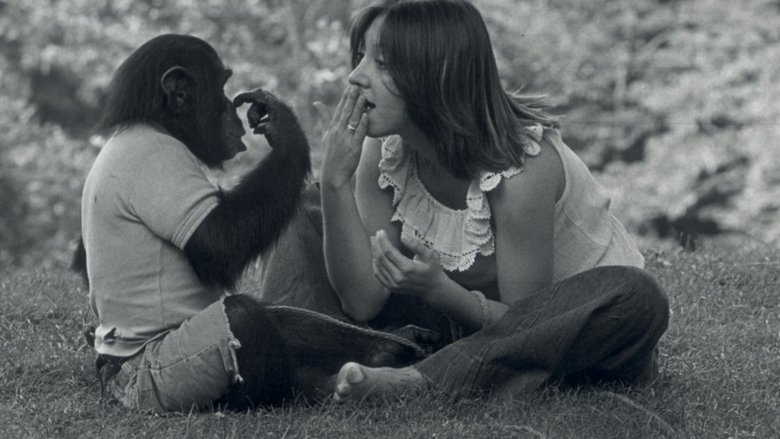

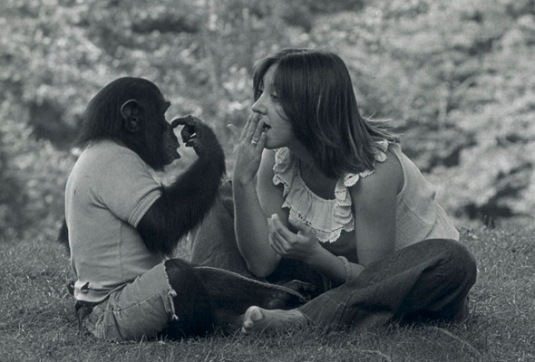

Eventually, Nim was taken away from the LaFarge's to be put into a more controlled environment. This is when he started to learn sign language. He was still in a really nice environment, though, and it looked like good times. He was surrounded by young, bright teachers who would take care of him and teach him and basically treat him like one of them. Nim got to go on hikes and talk to them about what they could hear and see; he was able to ask for food when he saw it; they even let him take a few puffs of their joints.  And Nim did learn over 125 signs - various food signs, basic verbs like "want" and "get", and others like "hug" and "kisses."

And Nim did learn over 125 signs - various food signs, basic verbs like "want" and "get", and others like "hug" and "kisses."

Unfortunately, though, as Nim grew and became less cuddly and more like an animal, they had to put him in an even more controlled environment. He was aggressive, often biting and scratching (and we all know the affects of that by now) to the point that Herb had to face facts and treat Nim like what he was - an animal. It's really heartbreaking watching little, trusting Nim being drugged up and led by the hand through the gates of some pretty horrific places, even at one point being brought to an animal testing centre. It was around this time that Herb began to run out of funding for his project, and coincidentally enough it was also around this time that Herbert Terrace admits to the world that his experiment had failed - not because he ran out of funding or because of any action on his part, but simply because he decided that all the signs Nim learned didn't really prove that Nim was communicating at all, but merely mimicking his teachers, and the only communication Nim would really take part in were instinctive ones to get him what he wanted (apple me eat, drink me Nim, for example).

I'd say the end result is probably up for interpretation, but it sure did seem like in the end, no matter how pampered and attended to Nim was in his life, it was always for the benefit of the doers and the thinkers, not Nim himself, and therefore, it really does say just as much about humans as it does about chimps.

Project Nim

2011, James Marsh

2011, James Marsh

|

I went into this film thinking I was going to see a study on how a chimp can be taken out of its own environment, brought into ours and proven to understand and accomplish real communication with a human being... and I did. Sort of. However, the overall consensus seems to say a lot more about people than it does about animals. For those of you who have ever watched James Marsh's previous documentary (Man on Wire), then you're probably already familiar with the style in which he craftily tells a story. Project Nim is wonderful for its heart and soul, but also brutal in the way it really exposes human nature.

Specifically, Nim was a chimpanzee who was the subject of scientific studies to do with animal language due to their DNA being identical to a humans to a crazy degree (98% or thereabouts). Herbert Terrace, the head of the study, wanted to challenge Chomsky's thesis that "only humans have language" by raising Nim in a human family treated like a child. Two weeks after he was born, he was separated from his mother, Carolyn, and put into the hands of a young couple with several young children of their own. The year was 1973. Funnily enough, the family who initially adopted Nim didn't really seem to take the study too seriously. The LaFarge's were sort of your typical liberal, hippy family of the mid-1970's, and Stephanie (Nim's "mom") wasn't very keen on keeping charts or notes or journals on Nim's progress. Therefore, there's lots of uber cute footage of little Nim running wild through the house, being curious and insanely lovable to the LeFarge's, but not a lot of "depth" beyond that. She didn't want to treat him like an experiment; it was pretty much like having another baby for her. She was excited to show Nim the world, but not to restrain him in any way. In fact, she wasn't even keen on teaching him language because she thought it would make him less unique.

|

And Nim did learn over 125 signs - various food signs, basic verbs like "want" and "get", and others like "hug" and "kisses."

And Nim did learn over 125 signs - various food signs, basic verbs like "want" and "get", and others like "hug" and "kisses."Unfortunately, though, as Nim grew and became less cuddly and more like an animal, they had to put him in an even more controlled environment. He was aggressive, often biting and scratching (and we all know the affects of that by now) to the point that Herb had to face facts and treat Nim like what he was - an animal. It's really heartbreaking watching little, trusting Nim being drugged up and led by the hand through the gates of some pretty horrific places, even at one point being brought to an animal testing centre. It was around this time that Herb began to run out of funding for his project, and coincidentally enough it was also around this time that Herbert Terrace admits to the world that his experiment had failed - not because he ran out of funding or because of any action on his part, but simply because he decided that all the signs Nim learned didn't really prove that Nim was communicating at all, but merely mimicking his teachers, and the only communication Nim would really take part in were instinctive ones to get him what he wanted (apple me eat, drink me Nim, for example).

I'd say the end result is probably up for interpretation, but it sure did seem like in the end, no matter how pampered and attended to Nim was in his life, it was always for the benefit of the doers and the thinkers, not Nim himself, and therefore, it really does say just as much about humans as it does about chimps.