← Back to Reviews

in

Frenzy

(1972, Alfred Hitchcock)

4 Stars (out of 4)

Known primarily as the first Hitchcock film to feature nudity (albeit through the use of body doubles), Frenzy repeatedly gets lost in the shuffle when discussing the director’s output throughout the latter stages of his career. Yet, even through the years since its first release, it can be argued that Frenzy is one of Hitchcock’s best films and the one that holds up the most by today’s standards – especially considering it is, without a doubt, his best acted film. The Master of Suspense populates the film with all the style, wit, sadism and sheer excitement that catapulted his earlier films to classic status; and not to mention the inclusion of a potato truck sequence that easily rivals the bird attack scene in The Birds, the crop-duster sequence in North by Northwest, and second only to Janet Leigh’s iconic death in Psycho.

The fact that the sequence is violent but morbidly hilarious – a serial killer desperately breaks the fingers of his victim’s hand after rigor mortis has set in so as to remove an incriminating piece of evidence - could be the reason why most people have chosen not to put it up with some of his best work. Describing too much of it would ruin the experience for people who haven’t seen it, but suffice it to say that if you’re not watching the scene with a bizarre fascination for the macabre, you’re not a Hitchcock fan.

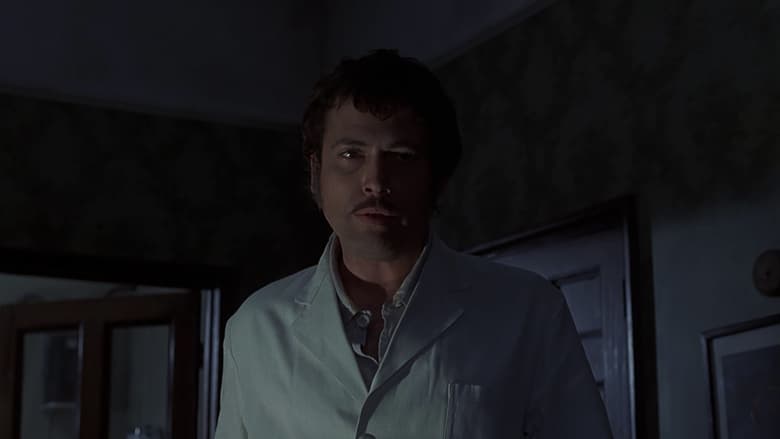

The first film shot in Britain since Hitchcock’s The Man Who Knew Too Much, Frenzy concerns the killings committed by The Necktie Murderer, a London-based serial killer who rapes and strangles women with fashionable neckties. Like most of Hitchcock’s thrillers, the plot undoubtedly falls on the shoulders of a wrongfully accused innocent man who must evade the authorities while desperately trying to catch the real criminal. In this case, Richard Blaney (Jon Finch), a recently fired bartender, becomes a man on-the-run after his ex-wife, who he was seen having a drunken argument with, is found murdered in her office with a tie wrapped around her throat. Hounded by Chief Inspector Oxford (a brilliantly understated and hilarious performance by Alex McCowen), Blaney exhibits all the signs of a guilty man: he’s poor, unrefined, drinks heavily, and quick to lose his temper. Hitchcock and screenwriter Anthony Schaffer play up these faults in order to break down the conventional stereotypes of a sexual predator. This is contrasted with Robert Husk (Barry Foster), a friend of Blaney, and well-to-do businessman who lives with his mother.

The reason the film works so well is due in large part to the brilliant and largely unknown British cast assembled. Jon Finch and Barry Foster radiate with conviction and menace that is a far cry from Raymond Burr’s lumbering Mr. Thorwald in Rear Window. Also, Anthony Shaffer’s script is a terrifically wicked attack on sexuality, family life, and the sensationalism derived from the heinous crimes committed, even going so far as implicating the audience in its fascination with the murders. The scene involving the murder of Blaney’s ex-wife, Brenda (Barbara Leigh-Hunt), is highly unsettling due to the long build-up, the assault, rape, and eventual strangulation. Forcing the audience to watch this sequence but cutting short a sequence later in the film (more on that below) forces the audience to re-imagine the death in their mind, thus implicating them in the crime.

This later sequence, involving the killer and Blaney’s girlfriend, Barbara (Anna Massey) being led up the stairs to the killer’s apartment is done in one long take that starts on the street and ends with the two walking into the apartment together, at which point the camera retreats back down the stairs and settles across the street from the building. The assured directing showcases Hitchcock’s deft style and his faith in his audience - who, knowing what will come next, is left to simply imagine what will happen to Barbara. A nice touch is added when the killer utters the same line he spoke just before killing Brenda earlier. In just this one, unbroken shot, Hitchcock established that he still was the complete master of the medium.

(1972, Alfred Hitchcock)

4 Stars (out of 4)

Known primarily as the first Hitchcock film to feature nudity (albeit through the use of body doubles), Frenzy repeatedly gets lost in the shuffle when discussing the director’s output throughout the latter stages of his career. Yet, even through the years since its first release, it can be argued that Frenzy is one of Hitchcock’s best films and the one that holds up the most by today’s standards – especially considering it is, without a doubt, his best acted film. The Master of Suspense populates the film with all the style, wit, sadism and sheer excitement that catapulted his earlier films to classic status; and not to mention the inclusion of a potato truck sequence that easily rivals the bird attack scene in The Birds, the crop-duster sequence in North by Northwest, and second only to Janet Leigh’s iconic death in Psycho.

The fact that the sequence is violent but morbidly hilarious – a serial killer desperately breaks the fingers of his victim’s hand after rigor mortis has set in so as to remove an incriminating piece of evidence - could be the reason why most people have chosen not to put it up with some of his best work. Describing too much of it would ruin the experience for people who haven’t seen it, but suffice it to say that if you’re not watching the scene with a bizarre fascination for the macabre, you’re not a Hitchcock fan.

The first film shot in Britain since Hitchcock’s The Man Who Knew Too Much, Frenzy concerns the killings committed by The Necktie Murderer, a London-based serial killer who rapes and strangles women with fashionable neckties. Like most of Hitchcock’s thrillers, the plot undoubtedly falls on the shoulders of a wrongfully accused innocent man who must evade the authorities while desperately trying to catch the real criminal. In this case, Richard Blaney (Jon Finch), a recently fired bartender, becomes a man on-the-run after his ex-wife, who he was seen having a drunken argument with, is found murdered in her office with a tie wrapped around her throat. Hounded by Chief Inspector Oxford (a brilliantly understated and hilarious performance by Alex McCowen), Blaney exhibits all the signs of a guilty man: he’s poor, unrefined, drinks heavily, and quick to lose his temper. Hitchcock and screenwriter Anthony Schaffer play up these faults in order to break down the conventional stereotypes of a sexual predator. This is contrasted with Robert Husk (Barry Foster), a friend of Blaney, and well-to-do businessman who lives with his mother.

The reason the film works so well is due in large part to the brilliant and largely unknown British cast assembled. Jon Finch and Barry Foster radiate with conviction and menace that is a far cry from Raymond Burr’s lumbering Mr. Thorwald in Rear Window. Also, Anthony Shaffer’s script is a terrifically wicked attack on sexuality, family life, and the sensationalism derived from the heinous crimes committed, even going so far as implicating the audience in its fascination with the murders. The scene involving the murder of Blaney’s ex-wife, Brenda (Barbara Leigh-Hunt), is highly unsettling due to the long build-up, the assault, rape, and eventual strangulation. Forcing the audience to watch this sequence but cutting short a sequence later in the film (more on that below) forces the audience to re-imagine the death in their mind, thus implicating them in the crime.

This later sequence, involving the killer and Blaney’s girlfriend, Barbara (Anna Massey) being led up the stairs to the killer’s apartment is done in one long take that starts on the street and ends with the two walking into the apartment together, at which point the camera retreats back down the stairs and settles across the street from the building. The assured directing showcases Hitchcock’s deft style and his faith in his audience - who, knowing what will come next, is left to simply imagine what will happen to Barbara. A nice touch is added when the killer utters the same line he spoke just before killing Brenda earlier. In just this one, unbroken shot, Hitchcock established that he still was the complete master of the medium.