← Back to Reviews

in

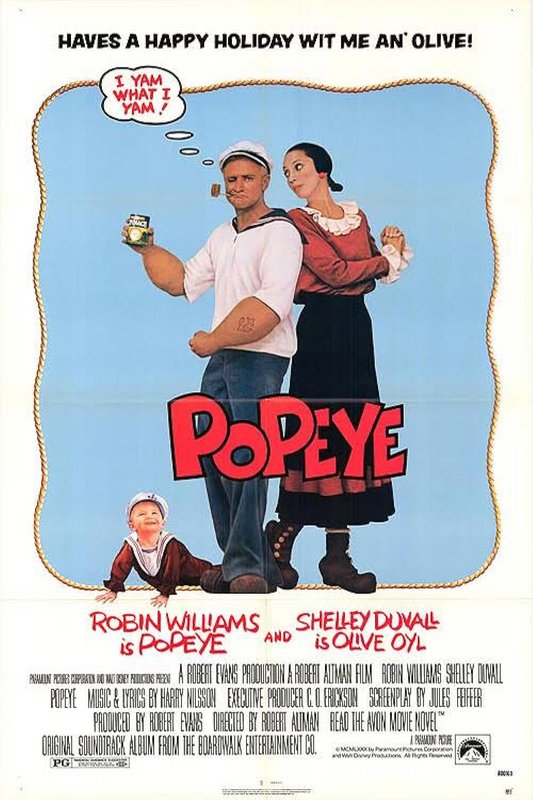

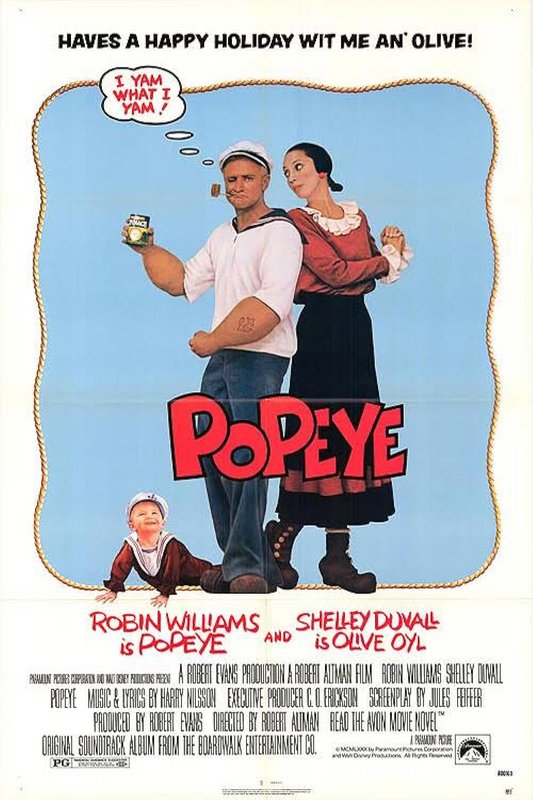

Popeye - 1980

Directed by Robert Altman

Written by Jules Feiffer

Based on the comic strip by E. C. Segar

Starring Robin Williams, Shelley Duvall, Paul L. Smith, Paul Dooley, Ray Walston & Richard Libertini

Are we only just now able to appreciate Robert Altman's Popeye? Did it confound us at the time of it's release? Nothing up on that screen is comparable to any other such film, and off-screen it's equally hard to find examples to judge it's production against. The idea alone is remarkable and hard to process mentally - the director of films such as Images, Nashville and 3 Women, an anti-establishment, arthouse/experimental filmmaker taking on a big budget, property-based, live-action comic strip musical. Altman's previous films defied convention, and in some cases had paid dearly for doing so. Now he was to direct what was anticipated as one of the biggest films of the year for Paramount - a position he had never been in before. The result of this strange marriage was indeed remarkable, but tagged a "fiasco", "failure" and "bomb" - despite being none of those things. Popeye was one of the biggest moneymakers Paramount had for the year it was released, and has critics looking at it today and seeing something that wasn't seen back then - an extraordinary filmmaking achievement. A wonderful film.

The production had as it's ground zero a weird shanty town constructed from scratch on the island of Malta. It's been a tourist attraction to this day - given the moniker "Popeye Village". This location, purposely grey to let the 'cartoon characters' stand out as if this were a live-action comic strip (it has since been spruced up to flower-garden standard), really gives the film a firm grounding and sense of reality. "Sweethaven" - it's characters sing what amounts to a 'national anthem' at the start of the film which familiarizes us to a town which feels not only like a country unto itself, but almost a reality disconnected from any outside contact. That would explain why Popeye (Robin Williams) is ogled uncertainly by all of the other characters when he arrives as the 'stranger'. In it roam all of the familiar characters from the comic strip and cartoon. Olive Oyl (Shelley Duvall) and Bluto (Paul L. Smith) are the standouts, but we also get the likes of Wimpy (Paul Dooley), Castor Oyl (Donovan Scott), Poopdeck Pappy (Ray Walston) and George W. Geezil (Richard Libertini).

Popeye rows in from the sea to Sweethaven on a quest to find his long lost father, who abandoned him at the age of two. On arrival in the crooked shanty town he takes up residence in the Oyl household, with Castor, Nana (Roberta Maxwell), Cole (MacIntyre Dixon) and of course the clumsy Olive, who is betrothed to Bluto. Bluto controls Sweethaven while the Commodore is seemingly away, and does so with an iron fist - declaring curfews along with often losing his temper and destroying things. On the eve of her wedding a celebration is held, but Olive, who has been engaged a number of times before, sneaks away, coming to the realisation that Bluto isn't for her - and she runs into Popeye, who is having trouble fitting in. The two share a dizzy kind of chemistry. Both come across an abandoned baby in a basket and, naming him Swee'Pea (Wesley Ivan Hurt), decide to raise him together. Eventually Popeye challenges Bluto's rule of Sweethaven by various means - including a boxing match, uncovering Swee'Pea's talents of foretelling the future and the discovery of what has actually happened to the Commodore.

It's not a narrative that neatly unfolds or tells a compelling story (something of the western "a stranger rides into town" theme) - but this is Popeye, and the comic strip nature of that fact was something producer Robert Evans, screenwriter Jules Feiffer and Robert Altman himself wanted to preserve. As soon as the film begins you'll notice a marked difference between this and most films of it's ilk - most apparent the way dialogue is kind of quietly muttered and mumbled, as if what's being said is background to more important matters. There are some funny asides that Robin Williams comes out with that are barely audible (Williams had to redub his audio because talking with a pipe in his mouth made his recorded lines on set not clear enough - and yet it's still hardly clear in any event.) Then the first musical number is a strange amalgam of regular dialogue and semi-apparent tune, centered on Popeye's occasional "Blow me down!" as he comes across many a curiosity in Sweethaven. It's almost as if Altman is slowly acclimating us to what's to come. During all of this we meet various strange inhabitants in the foreground and background - and it surely is a magical comic strip come to life.

Popeye's music, musical numbers and general dialogue is in general clear enough - but Altman doesn't let go of his penchant for playing with how audible it is, and what that dialogue is competing with for our attention. Jules Feiffer was beside himself after a preview screening when he realised that much of it couldn't be clearly discerned - something Altman attended to when other patrons complained about not being able to hear it. Although much clearer now, it's still an interestingly novel way to present a comic strip musical movie - full of curious routines and strange songs written by Harry Nilsson. It gives the mind little basis for comparison, because there's not much out there that is like this. Altman added professional clowns and circus performers to the cast, giving us wild real-life cartoon characters performing unusual stunts and really embodying their respective characters. Most noticeable is former clown Bill Irwin, making his debut here as Ham Gravy. He contorts his body and does such wonderful work he needs no dialogue at all.

The production design (Wolf Kroeger) is remarkable, the set decoration (Oscar-winner Jack Stephens) is remarkable and the costume design (Scott Bushnell) is lovingly true to Popeye's origins and history. The Sweethaven set is simply incredible, and one of the best of it's sort I've ever seen. The cinematography by Giuseppe Rotunno (just coming off an Oscar win for All That Jazz) is emblematic of a Robert Altman film - still full of those zooms and inventive Altmanesque shots. The actors really embrace the whole feel of this "live comic strip" cinematic exercise - Shelley Duvall was, as Altman said, born to play Olive Oyl, and Robin Williams is also giving 100%. For Duvall, this was her 7th time around with this director, and including The Shining, which had come out earlier that same year, she'd only been in two feature films not directed by him. Regulars Paul Dooley (4th Altman film) and Allan F. Nicholls (6th Altman film) as Rough House continued his penchant for sticking with certain actors.

So overall, speaking generally, my thoughts and feelings have also changed over time regarding Popeye, and I think the film gains a lot when you're more of a film lover. If you're a kid, and just want to be entertained, Popeye is on shakier ground - although that's not to say many kids wouldn't love it. It's not as vivacious, simple or loud as some kid's films are - and depends on careful consideration of details that may be missed by a younger audience. It's almost too good for it's own good. But while some of the effects - such as when Donovan Scott's Castor Oyl is kicked out of a boxing ring, flying through the air as if launched by a cannon - are marvelous, there are the occasional low points. Take for example a giant octopus near the end that behaves more like the one in Ed Wood's Bride of the Monster than anything you'd expect from a film such as this. I'm not complaining though - overall, this is a beautiful and well realised film. I've seen it as middling for a long time - but giving it more careful consideration, I've come to love it. It's so rich in detail, and naturally comedic, that it's grown on me.

For quite a while, I've been seeing Popeye as a kind of dividing line for Altman. A cut-off point, after which his stature diminished for just over a decade until he reemerged with The Player in 1992. If that's true, then it's not because of the quality of this film, or how well it did at the box office - it was simply because the heads of production and studio bosses in Hollywood hated the man, and actually played down Popeye's success, just so they could be rid of him. It may not be universally beloved, but it's a filmmaking achievement and seems to be admired by many critics who approach it today - as if film lovers in general weren't ready for that kind of movie back in 1980. I was actually surprised by my recent reaction to it - and my desire to watch it again so soon after taking it on. It's a rare example of a living breathing comic strip, and one transposed so faithfully from the page to the screen. That talented group, sequestered half the world away in Malta, really gave Popeye their loving best. We should love them all in return. If you haven't seen it for a while, or have never seen it, I suggest giving it a viewing. You might just find a new appreciation for it.

Popeye - 1980

Directed by Robert Altman

Written by Jules Feiffer

Based on the comic strip by E. C. Segar

Starring Robin Williams, Shelley Duvall, Paul L. Smith, Paul Dooley, Ray Walston & Richard Libertini

Are we only just now able to appreciate Robert Altman's Popeye? Did it confound us at the time of it's release? Nothing up on that screen is comparable to any other such film, and off-screen it's equally hard to find examples to judge it's production against. The idea alone is remarkable and hard to process mentally - the director of films such as Images, Nashville and 3 Women, an anti-establishment, arthouse/experimental filmmaker taking on a big budget, property-based, live-action comic strip musical. Altman's previous films defied convention, and in some cases had paid dearly for doing so. Now he was to direct what was anticipated as one of the biggest films of the year for Paramount - a position he had never been in before. The result of this strange marriage was indeed remarkable, but tagged a "fiasco", "failure" and "bomb" - despite being none of those things. Popeye was one of the biggest moneymakers Paramount had for the year it was released, and has critics looking at it today and seeing something that wasn't seen back then - an extraordinary filmmaking achievement. A wonderful film.

The production had as it's ground zero a weird shanty town constructed from scratch on the island of Malta. It's been a tourist attraction to this day - given the moniker "Popeye Village". This location, purposely grey to let the 'cartoon characters' stand out as if this were a live-action comic strip (it has since been spruced up to flower-garden standard), really gives the film a firm grounding and sense of reality. "Sweethaven" - it's characters sing what amounts to a 'national anthem' at the start of the film which familiarizes us to a town which feels not only like a country unto itself, but almost a reality disconnected from any outside contact. That would explain why Popeye (Robin Williams) is ogled uncertainly by all of the other characters when he arrives as the 'stranger'. In it roam all of the familiar characters from the comic strip and cartoon. Olive Oyl (Shelley Duvall) and Bluto (Paul L. Smith) are the standouts, but we also get the likes of Wimpy (Paul Dooley), Castor Oyl (Donovan Scott), Poopdeck Pappy (Ray Walston) and George W. Geezil (Richard Libertini).

Popeye rows in from the sea to Sweethaven on a quest to find his long lost father, who abandoned him at the age of two. On arrival in the crooked shanty town he takes up residence in the Oyl household, with Castor, Nana (Roberta Maxwell), Cole (MacIntyre Dixon) and of course the clumsy Olive, who is betrothed to Bluto. Bluto controls Sweethaven while the Commodore is seemingly away, and does so with an iron fist - declaring curfews along with often losing his temper and destroying things. On the eve of her wedding a celebration is held, but Olive, who has been engaged a number of times before, sneaks away, coming to the realisation that Bluto isn't for her - and she runs into Popeye, who is having trouble fitting in. The two share a dizzy kind of chemistry. Both come across an abandoned baby in a basket and, naming him Swee'Pea (Wesley Ivan Hurt), decide to raise him together. Eventually Popeye challenges Bluto's rule of Sweethaven by various means - including a boxing match, uncovering Swee'Pea's talents of foretelling the future and the discovery of what has actually happened to the Commodore.

It's not a narrative that neatly unfolds or tells a compelling story (something of the western "a stranger rides into town" theme) - but this is Popeye, and the comic strip nature of that fact was something producer Robert Evans, screenwriter Jules Feiffer and Robert Altman himself wanted to preserve. As soon as the film begins you'll notice a marked difference between this and most films of it's ilk - most apparent the way dialogue is kind of quietly muttered and mumbled, as if what's being said is background to more important matters. There are some funny asides that Robin Williams comes out with that are barely audible (Williams had to redub his audio because talking with a pipe in his mouth made his recorded lines on set not clear enough - and yet it's still hardly clear in any event.) Then the first musical number is a strange amalgam of regular dialogue and semi-apparent tune, centered on Popeye's occasional "Blow me down!" as he comes across many a curiosity in Sweethaven. It's almost as if Altman is slowly acclimating us to what's to come. During all of this we meet various strange inhabitants in the foreground and background - and it surely is a magical comic strip come to life.

Popeye's music, musical numbers and general dialogue is in general clear enough - but Altman doesn't let go of his penchant for playing with how audible it is, and what that dialogue is competing with for our attention. Jules Feiffer was beside himself after a preview screening when he realised that much of it couldn't be clearly discerned - something Altman attended to when other patrons complained about not being able to hear it. Although much clearer now, it's still an interestingly novel way to present a comic strip musical movie - full of curious routines and strange songs written by Harry Nilsson. It gives the mind little basis for comparison, because there's not much out there that is like this. Altman added professional clowns and circus performers to the cast, giving us wild real-life cartoon characters performing unusual stunts and really embodying their respective characters. Most noticeable is former clown Bill Irwin, making his debut here as Ham Gravy. He contorts his body and does such wonderful work he needs no dialogue at all.

The production design (Wolf Kroeger) is remarkable, the set decoration (Oscar-winner Jack Stephens) is remarkable and the costume design (Scott Bushnell) is lovingly true to Popeye's origins and history. The Sweethaven set is simply incredible, and one of the best of it's sort I've ever seen. The cinematography by Giuseppe Rotunno (just coming off an Oscar win for All That Jazz) is emblematic of a Robert Altman film - still full of those zooms and inventive Altmanesque shots. The actors really embrace the whole feel of this "live comic strip" cinematic exercise - Shelley Duvall was, as Altman said, born to play Olive Oyl, and Robin Williams is also giving 100%. For Duvall, this was her 7th time around with this director, and including The Shining, which had come out earlier that same year, she'd only been in two feature films not directed by him. Regulars Paul Dooley (4th Altman film) and Allan F. Nicholls (6th Altman film) as Rough House continued his penchant for sticking with certain actors.

So overall, speaking generally, my thoughts and feelings have also changed over time regarding Popeye, and I think the film gains a lot when you're more of a film lover. If you're a kid, and just want to be entertained, Popeye is on shakier ground - although that's not to say many kids wouldn't love it. It's not as vivacious, simple or loud as some kid's films are - and depends on careful consideration of details that may be missed by a younger audience. It's almost too good for it's own good. But while some of the effects - such as when Donovan Scott's Castor Oyl is kicked out of a boxing ring, flying through the air as if launched by a cannon - are marvelous, there are the occasional low points. Take for example a giant octopus near the end that behaves more like the one in Ed Wood's Bride of the Monster than anything you'd expect from a film such as this. I'm not complaining though - overall, this is a beautiful and well realised film. I've seen it as middling for a long time - but giving it more careful consideration, I've come to love it. It's so rich in detail, and naturally comedic, that it's grown on me.

For quite a while, I've been seeing Popeye as a kind of dividing line for Altman. A cut-off point, after which his stature diminished for just over a decade until he reemerged with The Player in 1992. If that's true, then it's not because of the quality of this film, or how well it did at the box office - it was simply because the heads of production and studio bosses in Hollywood hated the man, and actually played down Popeye's success, just so they could be rid of him. It may not be universally beloved, but it's a filmmaking achievement and seems to be admired by many critics who approach it today - as if film lovers in general weren't ready for that kind of movie back in 1980. I was actually surprised by my recent reaction to it - and my desire to watch it again so soon after taking it on. It's a rare example of a living breathing comic strip, and one transposed so faithfully from the page to the screen. That talented group, sequestered half the world away in Malta, really gave Popeye their loving best. We should love them all in return. If you haven't seen it for a while, or have never seen it, I suggest giving it a viewing. You might just find a new appreciation for it.