← Back to Reviews

in

This review contains spoilers.

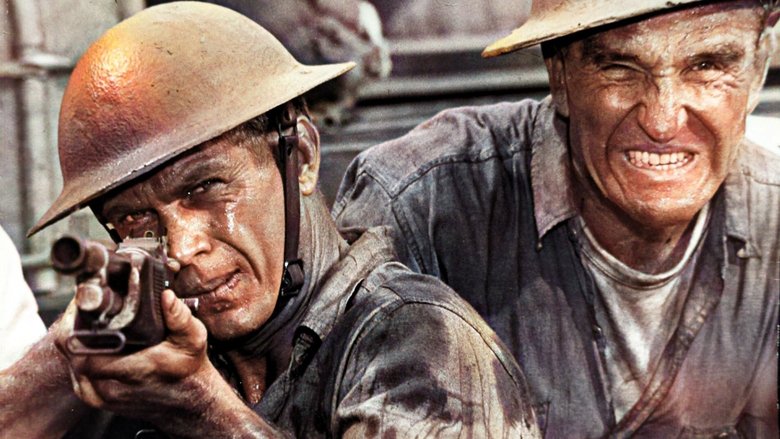

I watched this as part of the Hollywood Chinese series on the Criterion Channel, so naturally my attention turned to the portrayal of the Chinese characters in the movie. The last movie I watched from the series, Daughter of the Dragon, was not free from negative stereotypes. But it surprised me with the way they were navigated, getting some mileage out of the tension between the magnetism of the stars and the roles they either embraced or repelled, depending on the situation. The first hour into The Sand Pebbles, Robert Wise’s epic about a US Navy gunboat on Yangtze River Patrol in 1920s China, I did not think it was finding such ways to subvert the material. The portrayal of the Chinese here is at best condescending and at worst outright xenophobic, with the positive characters infantilized and the negative characters outright treacherous.

One of the positive characters is a coolie played by Mako, who the gruff but upright hero played by Steve McQueen (effortlessly cool and stoic as always) teaches ship maintenance and courage. The character is portrayed sympathetically, cooperating with McQueen even when his coolie boss discourages it, but also as childlike, absorbing lessons from McQueen only in simplistic forms. Mako is likable in the role, but there’s only so much he can do in the face of such blatant stereotyping. The movie does try to bestow upon him a certain dignity, having us root for him in a boxing match against a thuggish racist aboard the same ship, but cuts his arc short in a startlingly violent (by mid-‘60s standards) scene in which he is brutally tortured by locals in full view of McQueen’s ship and eventually put out of his misery by McQueen himself.

The other positive Chinese character is a woman played by Marayat Andriane forced to work as a hostess in a bar where she’s pressured to be a prostitute, but falls in love with McQueen’s shipmate Richard Attenborough. The sexually charged nature of her indenture to a slimy creditor (James Hong in a minor role), and the unimaginably horrible fate she suffers (promptly blamed on McQueen by the real perpetrators) highlights the treachery and cruelty of the Chinese. Yet I think Andriane is able (or at least given the screentime) to humanize her character more than Mako, and I did find her arc quite affecting. On a side note, what might really throw viewers for a loop is that Andriane, whose character is a bastion of purity in a seedy, sinister milieu, is also known as Emmanuelle Arsan, who wrote the Emmanuelle books supposedly inspired by her real life sexual adventures. Needless to say her character here does not partake in similar activities.

That being said, similar to Zulu, which set up a bunch of cliches in its first half only to blast through them one by one in the second half, this movie substantially complicates matters. As tensions rise between the Communists and Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists, with both sides itching to bait the American presence into combat, the heroes retreat onto the ship, and the surrounding events become filtered through an increasingly narrow perspective as they hold fast on this aquatic stronghold. Adding to the tension is that the ship is essentially stranded due to low water levels, and under orders not to fire at the hostile locals. This was released as the Vietnam War was starting to ramp up, and it definitely invites parallels to the situation, although depending on your political views, your sympathy may be limited for the imperialist dilemma of maintaining an image of strength while being unable to use force and futility of humanitarian aims when you’re an unwanted presence. I don’t know how much I agreed with the film’s conclusions, but I found the way it grappled with this subject pretty fascinating.

These ideas come to a head in the film’s most thrilling sequence, where the gunboat fights its way through a blockade set up by Chinese boats. It’s exhilarating not just because it’s a well directed action sequence, which it certainly is, but also because of the way it shows war as a unifying force, diffusing tensions among the crew as they direct their aggression towards a common enemy. And the switch from relatively distanced naval combat to swashbuckler style action plays like a commentary on how these characters view the locals (“pirates”, to use one character’s words). And a late reveal involving a previously minor character gives us a sense of how badly the heroes had misread the locals’ motivations. Again, the Vietnam metaphor can’t be ignored. I do think the performance of Richard Crenna as the ship’s commanding officer is pretty key to all of this as well. Crenna can have a certain stodginess and that quality is well deployed here, his control of the situation proving increasingly tenuous in the face of the mounting tensions among the locals and on his own ship.

And on the whole, this is just a gripping piece of capital-C Cinema. I’m a sucker for any movie from this era with a sizable budget, and I certainly found the substantial production values, used to meticulously recreate 1920s China, appropriately dazzling. But this is directed by Robert Wise, who as in West Side Story, uses that scale in the service of several bracingly directed sequences. There’s of course the aforementioned naval battle, but even a smaller sequence like a brawl between McQueen and some unfriendly locals turns into a thrilling shadowplay. And there’s the final sequence, a suicidal shootout lent an immense poignancy and futility by the cavernous, shadowy soundstage it’s set on. It’s hard not to be swept up by this, and it’s hard not to feel implicated either.

The Sand Pebbles (Wise, 1966)

This review contains spoilers.

I watched this as part of the Hollywood Chinese series on the Criterion Channel, so naturally my attention turned to the portrayal of the Chinese characters in the movie. The last movie I watched from the series, Daughter of the Dragon, was not free from negative stereotypes. But it surprised me with the way they were navigated, getting some mileage out of the tension between the magnetism of the stars and the roles they either embraced or repelled, depending on the situation. The first hour into The Sand Pebbles, Robert Wise’s epic about a US Navy gunboat on Yangtze River Patrol in 1920s China, I did not think it was finding such ways to subvert the material. The portrayal of the Chinese here is at best condescending and at worst outright xenophobic, with the positive characters infantilized and the negative characters outright treacherous.

One of the positive characters is a coolie played by Mako, who the gruff but upright hero played by Steve McQueen (effortlessly cool and stoic as always) teaches ship maintenance and courage. The character is portrayed sympathetically, cooperating with McQueen even when his coolie boss discourages it, but also as childlike, absorbing lessons from McQueen only in simplistic forms. Mako is likable in the role, but there’s only so much he can do in the face of such blatant stereotyping. The movie does try to bestow upon him a certain dignity, having us root for him in a boxing match against a thuggish racist aboard the same ship, but cuts his arc short in a startlingly violent (by mid-‘60s standards) scene in which he is brutally tortured by locals in full view of McQueen’s ship and eventually put out of his misery by McQueen himself.

The other positive Chinese character is a woman played by Marayat Andriane forced to work as a hostess in a bar where she’s pressured to be a prostitute, but falls in love with McQueen’s shipmate Richard Attenborough. The sexually charged nature of her indenture to a slimy creditor (James Hong in a minor role), and the unimaginably horrible fate she suffers (promptly blamed on McQueen by the real perpetrators) highlights the treachery and cruelty of the Chinese. Yet I think Andriane is able (or at least given the screentime) to humanize her character more than Mako, and I did find her arc quite affecting. On a side note, what might really throw viewers for a loop is that Andriane, whose character is a bastion of purity in a seedy, sinister milieu, is also known as Emmanuelle Arsan, who wrote the Emmanuelle books supposedly inspired by her real life sexual adventures. Needless to say her character here does not partake in similar activities.

That being said, similar to Zulu, which set up a bunch of cliches in its first half only to blast through them one by one in the second half, this movie substantially complicates matters. As tensions rise between the Communists and Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists, with both sides itching to bait the American presence into combat, the heroes retreat onto the ship, and the surrounding events become filtered through an increasingly narrow perspective as they hold fast on this aquatic stronghold. Adding to the tension is that the ship is essentially stranded due to low water levels, and under orders not to fire at the hostile locals. This was released as the Vietnam War was starting to ramp up, and it definitely invites parallels to the situation, although depending on your political views, your sympathy may be limited for the imperialist dilemma of maintaining an image of strength while being unable to use force and futility of humanitarian aims when you’re an unwanted presence. I don’t know how much I agreed with the film’s conclusions, but I found the way it grappled with this subject pretty fascinating.

These ideas come to a head in the film’s most thrilling sequence, where the gunboat fights its way through a blockade set up by Chinese boats. It’s exhilarating not just because it’s a well directed action sequence, which it certainly is, but also because of the way it shows war as a unifying force, diffusing tensions among the crew as they direct their aggression towards a common enemy. And the switch from relatively distanced naval combat to swashbuckler style action plays like a commentary on how these characters view the locals (“pirates”, to use one character’s words). And a late reveal involving a previously minor character gives us a sense of how badly the heroes had misread the locals’ motivations. Again, the Vietnam metaphor can’t be ignored. I do think the performance of Richard Crenna as the ship’s commanding officer is pretty key to all of this as well. Crenna can have a certain stodginess and that quality is well deployed here, his control of the situation proving increasingly tenuous in the face of the mounting tensions among the locals and on his own ship.

And on the whole, this is just a gripping piece of capital-C Cinema. I’m a sucker for any movie from this era with a sizable budget, and I certainly found the substantial production values, used to meticulously recreate 1920s China, appropriately dazzling. But this is directed by Robert Wise, who as in West Side Story, uses that scale in the service of several bracingly directed sequences. There’s of course the aforementioned naval battle, but even a smaller sequence like a brawl between McQueen and some unfriendly locals turns into a thrilling shadowplay. And there’s the final sequence, a suicidal shootout lent an immense poignancy and futility by the cavernous, shadowy soundstage it’s set on. It’s hard not to be swept up by this, and it’s hard not to feel implicated either.