← Back to Reviews

in

When it comes to certain genres, especially ones that are no longer in fashion, itís an unfortunate fact that a lot of them will contain negative stereotypes and condescending or outright hostile attitudes towards other cultures. I have a weakness for jungle adventures, but I canít deny that even ones I like espouse colonial attitudes and have less than admiring portrayals of the locals in whatever country they take place. I think itís possible to appreciate the positive qualities of these films without endorsing the negative ones, and perhaps healthy to try to understand how the interact, and Iím personally not a fan of the checklist approach I sometimes see taken towards evaluating art that contains such elements. Iím also not going to pretend my reactions are representative of the norm. For example, Iíve seen Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom cited as a blatant example of Hollywood racism, but as someone of South Asian descent, Iíve found it difficult to be offended by it because the portrayal of its Indian characters is so far over the top that it severs any relation to reality. (If anything, Iím more offended by Gunga Din, a movie I mostly enjoy quite a bit, as it doesnít seem quite as fantastical in this respect.)

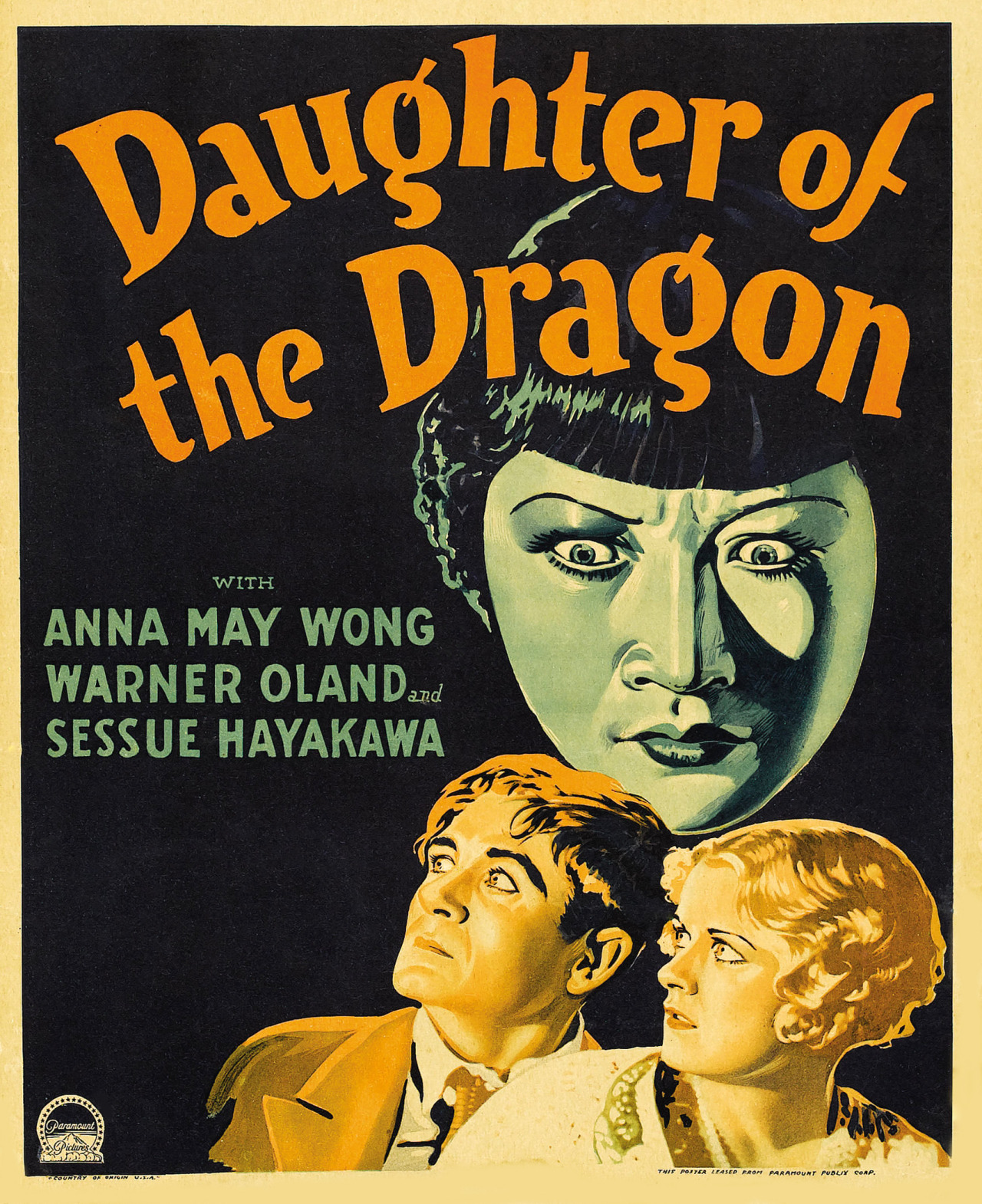

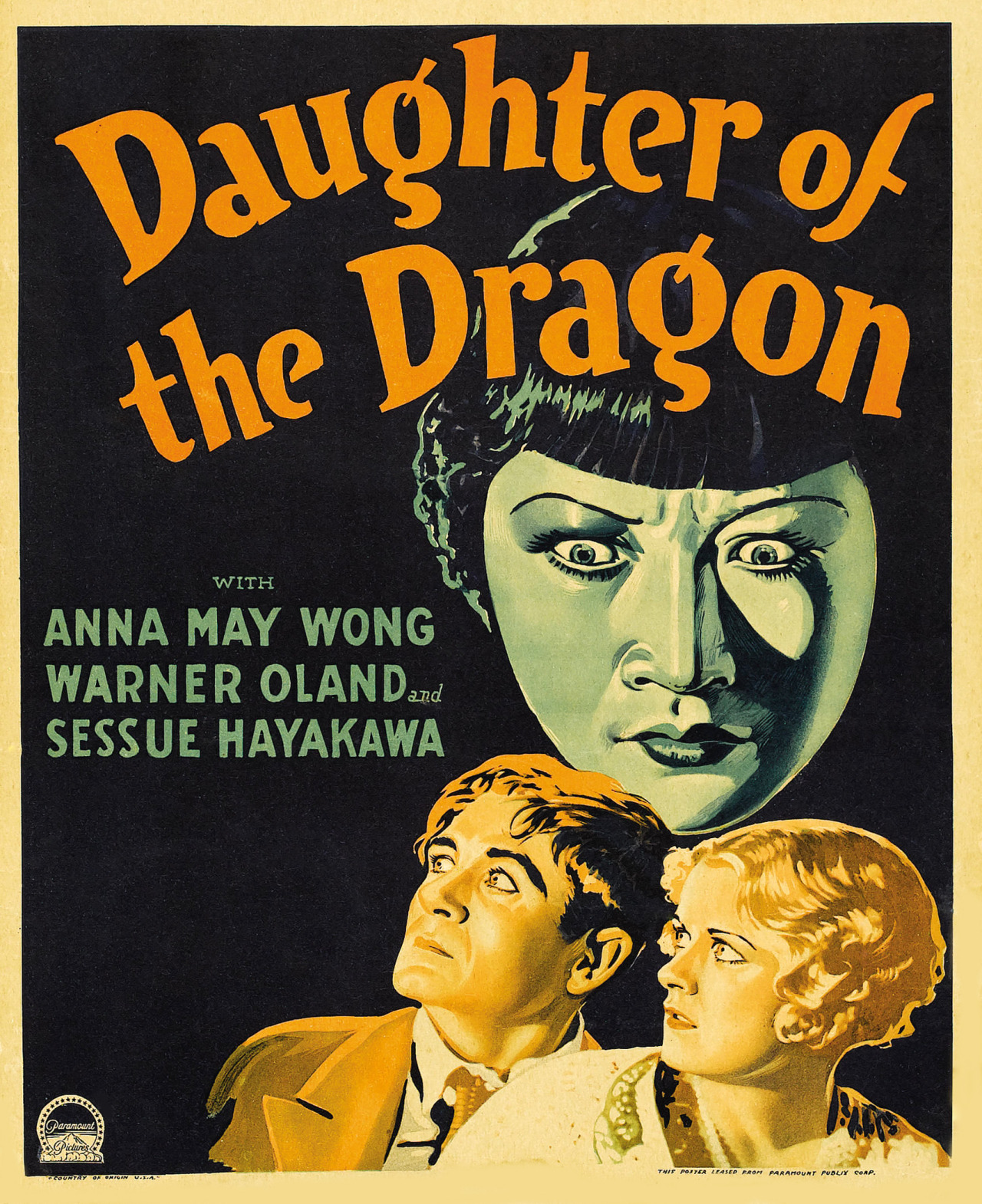

But I also think older movies can be more thoughtful about their use of such tropes than we give them credit for. Along the vein of Temple of Doom, if I can direct you to this great review of The Tiger of Eschnapur by the Letterboxd user sakana1, who argues much more articulately than I can about the ways in which the movie transcends the kind of orientalist pulp itís sometimes dismissed as. This dynamic is something I had in mind as I watched Daughter of the Dragon, a pre-code Fu Manchu picture currently playing on the Criterion Channel as part of the Hollywood Chinese series programmed by Arthur Dong. I am not a Fu Manchu expert, but I understand the series is full of portrayals of the Chinese as devious and villainous and is heavy on the use of yellowface, and thatís certainly the case here. But at the same time, I think the movie navigates these tropes more interestingly than I expected given the time period. For one thing, while Fu Manchu is portrayed by Warner Oland, a white actor in yellowface, heís quickly removed from the proceedings and instead we spend most of the movie with his daughter, played by Anna May Wong, and a heroic policeman, played by Sessue Hayakawa. Fu Manchu seeks revenge on a man for killing his ancestors, and pressures his daughter to continue his vendetta. The way Fu Manchu explains his motivations to his adversary reminds me of Charles Grodinís explanation of who lied to who first in Midnight Run. In a way, theyíre both right.

The programming notes indicate that this movie was notable for casting two Asian American stars and letting them share the screen together, and the fact that it lets them speak in their actual accents. (There is some talking in third person, but otherwise the stereotypical qualities of the dialogue are refreshingly toned down.) I was perhaps expecting them to be supporting players, but no, they are the stars of the movie, with one or both of them onscreen for most of the movie, and theyíre much more engaging than the less thoroughly developed white supporting characters. And beyond the amount of screentime, it is interesting to see how Wongís character navigates the pressure placed on her by her father to enact his sinister plan, and how she ingratiates herself with her targets, alternately pushing against and weaponizing stereotypes depending on the situation. Iíd like to get more context around the release of the movie (I have yet to see Dongís documentary Hollywood Chinese, which I hope will provide some interesting information), but judging by the fact that both Wong and Hayakawa are credited on the poster and that this wasnít the first Fu Manchu movie, I have to assume there was some intent in this subversion of expectations. (Alas, these empowering qualities didnít extend to the actorsí paycheques, as Wong apparently got paid half of what Oland did despite having substantially more screentime. Also, apparently this was made to capitalize on a Fu Manchu book that Paramount didnít even pay for the rights to adapt, so it seems the frugality ran deep.)

And the movie is otherwise a reasonably diverting suspense piece, with some nice stormy, rain-drenched atmosphere in the last act. Over the last few months, Iíve developed a growing appreciation for Ď30s Hollywood cinema, largely because I sometimes sleep quite poorly and wake up too early, and at well under an hour and a half, a lot of the movies are the perfect length to squeeze in before I need to log on for work. Clocking in at a cool seventy minutes, this hits the spot. This does however share the ďproblemĒ of the Ilsa and Olga movies in that casting an actress as the villain who happens to be substantially more magnetic and sexy than most of the supposed heroes will maybe have you rooting for her over them. All I can say that in one scene Wong wears an outfit with notably sparkly sleeves, which is very important to enjoyment of the movie. Yes, sheís a devious, murderous villainess, but the heart wants what it wants.

Daughter of the Dragon (Corrigan, 1931)

When it comes to certain genres, especially ones that are no longer in fashion, itís an unfortunate fact that a lot of them will contain negative stereotypes and condescending or outright hostile attitudes towards other cultures. I have a weakness for jungle adventures, but I canít deny that even ones I like espouse colonial attitudes and have less than admiring portrayals of the locals in whatever country they take place. I think itís possible to appreciate the positive qualities of these films without endorsing the negative ones, and perhaps healthy to try to understand how the interact, and Iím personally not a fan of the checklist approach I sometimes see taken towards evaluating art that contains such elements. Iím also not going to pretend my reactions are representative of the norm. For example, Iíve seen Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom cited as a blatant example of Hollywood racism, but as someone of South Asian descent, Iíve found it difficult to be offended by it because the portrayal of its Indian characters is so far over the top that it severs any relation to reality. (If anything, Iím more offended by Gunga Din, a movie I mostly enjoy quite a bit, as it doesnít seem quite as fantastical in this respect.)

But I also think older movies can be more thoughtful about their use of such tropes than we give them credit for. Along the vein of Temple of Doom, if I can direct you to this great review of The Tiger of Eschnapur by the Letterboxd user sakana1, who argues much more articulately than I can about the ways in which the movie transcends the kind of orientalist pulp itís sometimes dismissed as. This dynamic is something I had in mind as I watched Daughter of the Dragon, a pre-code Fu Manchu picture currently playing on the Criterion Channel as part of the Hollywood Chinese series programmed by Arthur Dong. I am not a Fu Manchu expert, but I understand the series is full of portrayals of the Chinese as devious and villainous and is heavy on the use of yellowface, and thatís certainly the case here. But at the same time, I think the movie navigates these tropes more interestingly than I expected given the time period. For one thing, while Fu Manchu is portrayed by Warner Oland, a white actor in yellowface, heís quickly removed from the proceedings and instead we spend most of the movie with his daughter, played by Anna May Wong, and a heroic policeman, played by Sessue Hayakawa. Fu Manchu seeks revenge on a man for killing his ancestors, and pressures his daughter to continue his vendetta. The way Fu Manchu explains his motivations to his adversary reminds me of Charles Grodinís explanation of who lied to who first in Midnight Run. In a way, theyíre both right.

The programming notes indicate that this movie was notable for casting two Asian American stars and letting them share the screen together, and the fact that it lets them speak in their actual accents. (There is some talking in third person, but otherwise the stereotypical qualities of the dialogue are refreshingly toned down.) I was perhaps expecting them to be supporting players, but no, they are the stars of the movie, with one or both of them onscreen for most of the movie, and theyíre much more engaging than the less thoroughly developed white supporting characters. And beyond the amount of screentime, it is interesting to see how Wongís character navigates the pressure placed on her by her father to enact his sinister plan, and how she ingratiates herself with her targets, alternately pushing against and weaponizing stereotypes depending on the situation. Iíd like to get more context around the release of the movie (I have yet to see Dongís documentary Hollywood Chinese, which I hope will provide some interesting information), but judging by the fact that both Wong and Hayakawa are credited on the poster and that this wasnít the first Fu Manchu movie, I have to assume there was some intent in this subversion of expectations. (Alas, these empowering qualities didnít extend to the actorsí paycheques, as Wong apparently got paid half of what Oland did despite having substantially more screentime. Also, apparently this was made to capitalize on a Fu Manchu book that Paramount didnít even pay for the rights to adapt, so it seems the frugality ran deep.)

And the movie is otherwise a reasonably diverting suspense piece, with some nice stormy, rain-drenched atmosphere in the last act. Over the last few months, Iíve developed a growing appreciation for Ď30s Hollywood cinema, largely because I sometimes sleep quite poorly and wake up too early, and at well under an hour and a half, a lot of the movies are the perfect length to squeeze in before I need to log on for work. Clocking in at a cool seventy minutes, this hits the spot. This does however share the ďproblemĒ of the Ilsa and Olga movies in that casting an actress as the villain who happens to be substantially more magnetic and sexy than most of the supposed heroes will maybe have you rooting for her over them. All I can say that in one scene Wong wears an outfit with notably sparkly sleeves, which is very important to enjoyment of the movie. Yes, sheís a devious, murderous villainess, but the heart wants what it wants.