← Back to Reviews

in

To be honest, I struggled with Cleopatra for the first half of its four hour runtime, finding much of the proceedings, if nice to look at, a little annoying, for lack of a better word. Only once I reached the midpoint did it start to click for me, and my problem with the earlier sections came into focus: Rex Harrison's performance as Julius Caesar. In scientific terms, he ****ing sucks. Perhaps I hold some pent up resentment from being forced to watch out of context snippets of My Fair Lady in high school while my eleventh grade English teacher did an abominable job of teaching us Pygmalion. But even without relitigating teenage grievances, I think the true measure of his performance is what he gives his costars to work with. A good actor can elevate the work of their costars. Harrison sinks them. Ostensibly madly in love with Elizabeth Taylor's Cleopatra, his smug, self-satisfied demeanour conveys only infatuation with himself, and makes the attraction Taylor is supposed to feel for him and the grand gestures she makes in the name of love feel inexplicable. I understand some reviews at the time were unkind to her performance, but they should have looked elsewhere.

When Caesar is killed during the Ides of March (which I guess is a spoiler, but it's also a historical event, so not really), it's less the tragedy the movie positions it as than his murderers doing everybody a huge favour. For one thing, it means the arrival of Richard Burton as Marc Antony, who becomes Cleopatra's lover for the second half of the movie. The difference between Burton and Harrison is vast and illuminating. Both have an undeniable theatricality to their performances, but where Harrison seems mostly impressed by his ability to deliver the florid dialogue he's given, Burton can imbue it with real feeling. The attraction between him and Taylor have the intensity of two lovers who were having a torrid affair offscreen and got married, divorced, remarried and re-divorced. The grand, nutty gestures they make in the name of love feel a lot more convincing, is what I'm saying. It's also worth noting that Burton plays one of the more credible scenes of drunkenness I can recall, likely because he had a lot of practice himself. The other major performance in the movie belongs to Roddy McDowall as Octavian, who has an off-kilter energy that complements the intensity of the central relationship without being overshadowed.

Speaking of grand, nutty gestures, there's a scene where Cleopatra's arrival is marked by a grandiose ceremony, including a giant sphinx brought forward through the crowd, and you look at all those extras and the elaborate sets and props that have been constructed, and it's hard not to have your breath taken away, at least a little. This was made in an era when movies could have ungodly amounts of money sunk into them and it could bear tactile rewards like this, but beyond the level of pure spectacle, I think it colours the movie pretty interestingly. I understand this was a notoriously troubled production, and scenes like Antony deciding to wage a battle on sea despite its strategic imprudence or Caesar railing against the limitations imposed on him by the Senate play like a director trying to assert his will over a production and battle with the money men. (It goes without saying the sea-set battle is one of the movie's highlights.) And in the closing stretches, the cavernous sets the characters find themselves in seem to amplify their emotions. Which is appropriate because this is a movie about characters who are larger than life and can shape history on a whim, consequences be damned. Is that a very democratic message? Absolutely not, but it does make for compelling cinema.

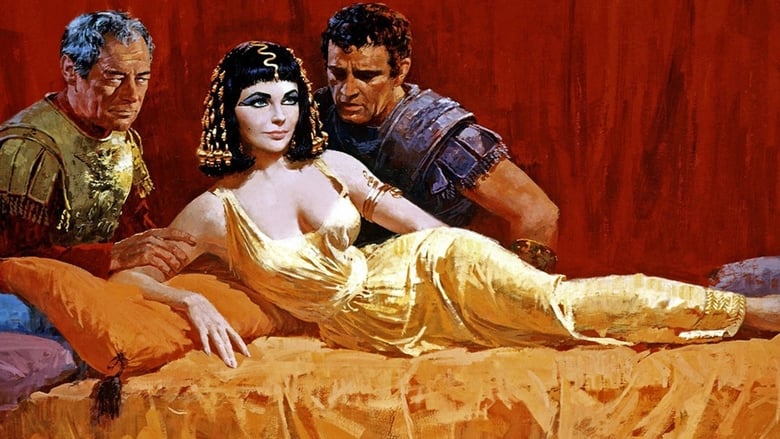

Cleopatra (Mankiewicz, 1963)

To be honest, I struggled with Cleopatra for the first half of its four hour runtime, finding much of the proceedings, if nice to look at, a little annoying, for lack of a better word. Only once I reached the midpoint did it start to click for me, and my problem with the earlier sections came into focus: Rex Harrison's performance as Julius Caesar. In scientific terms, he ****ing sucks. Perhaps I hold some pent up resentment from being forced to watch out of context snippets of My Fair Lady in high school while my eleventh grade English teacher did an abominable job of teaching us Pygmalion. But even without relitigating teenage grievances, I think the true measure of his performance is what he gives his costars to work with. A good actor can elevate the work of their costars. Harrison sinks them. Ostensibly madly in love with Elizabeth Taylor's Cleopatra, his smug, self-satisfied demeanour conveys only infatuation with himself, and makes the attraction Taylor is supposed to feel for him and the grand gestures she makes in the name of love feel inexplicable. I understand some reviews at the time were unkind to her performance, but they should have looked elsewhere.

When Caesar is killed during the Ides of March (which I guess is a spoiler, but it's also a historical event, so not really), it's less the tragedy the movie positions it as than his murderers doing everybody a huge favour. For one thing, it means the arrival of Richard Burton as Marc Antony, who becomes Cleopatra's lover for the second half of the movie. The difference between Burton and Harrison is vast and illuminating. Both have an undeniable theatricality to their performances, but where Harrison seems mostly impressed by his ability to deliver the florid dialogue he's given, Burton can imbue it with real feeling. The attraction between him and Taylor have the intensity of two lovers who were having a torrid affair offscreen and got married, divorced, remarried and re-divorced. The grand, nutty gestures they make in the name of love feel a lot more convincing, is what I'm saying. It's also worth noting that Burton plays one of the more credible scenes of drunkenness I can recall, likely because he had a lot of practice himself. The other major performance in the movie belongs to Roddy McDowall as Octavian, who has an off-kilter energy that complements the intensity of the central relationship without being overshadowed.

Speaking of grand, nutty gestures, there's a scene where Cleopatra's arrival is marked by a grandiose ceremony, including a giant sphinx brought forward through the crowd, and you look at all those extras and the elaborate sets and props that have been constructed, and it's hard not to have your breath taken away, at least a little. This was made in an era when movies could have ungodly amounts of money sunk into them and it could bear tactile rewards like this, but beyond the level of pure spectacle, I think it colours the movie pretty interestingly. I understand this was a notoriously troubled production, and scenes like Antony deciding to wage a battle on sea despite its strategic imprudence or Caesar railing against the limitations imposed on him by the Senate play like a director trying to assert his will over a production and battle with the money men. (It goes without saying the sea-set battle is one of the movie's highlights.) And in the closing stretches, the cavernous sets the characters find themselves in seem to amplify their emotions. Which is appropriate because this is a movie about characters who are larger than life and can shape history on a whim, consequences be damned. Is that a very democratic message? Absolutely not, but it does make for compelling cinema.