← Back to Reviews

in

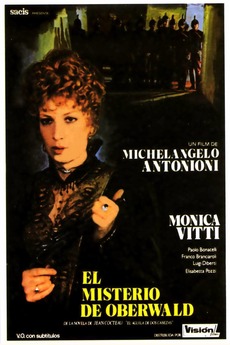

ANTONIONI, COMPLIMENTS OF GOLDIE GARDNER

Sometime in early 1980, one of Michaelangelo Antonioni’s children must have interrupted his dinner to tell him someone on the TV had just asked to talk to him. The matter was urgent. He must put down his fork immediately and contribute whatever he could afford to help. Shortly thereafter, following some negotiations of whether he’d prefer the Bob Ross tote bag or the Oscar the Grouch belt buckle, public broadcasting in Buffalo had secured the rights to the modernist master's next film.

Or so I assume. There seems no other explanation for The Mystery of Oberwald’s bad television vibes or its cheaply rendered lifelessness. It’s almost as if all his energy was spent waiting by the mailbox for his Thank You Gifts to arrive and there was nothing left over for the movie. Maybe this payment simply never came and he thinks this absolves him of the slow drying mess he’s created here. In any case, I watched it, and its curiosity factor seemed just enough to pull me through to the end of its ghastly slow runtime. But in the end, I was only left with questions.

Why? What? Huh?

Making the perverse choice to record Oberwald directly onto video, it doesn’t take long for it to become very hard to reconcile what we are watching with anything that has anything whatsoever to do with Antonioni. There will be brief moments of gracefully rendered camera movements, as well as his talent for asymmetrical compositions that make us want to look closer. These will be a nice call backs to a better time in the director's career, but to what end? What exactly are we being made to look more closely at? How blurry does he want this to get?

Ultimately, these will only be momentary and empty flashes of the director we know. The rest of the time we can’t help but be put off by how unpleasant everything is to look at. It seems to lack all sense of grace, deliberately embracing an ugly modernity that would unfortunately become dated almost immediately. As a result, we can’t help but be pulled out of the moment every time we watch the zoom of a lowly camrecorder slowly approach the stony visage of Monica Vitti. Instead, it feels we should be inching closer to some looming playground embarrassment, and that the actress, instead of staring at foliage and droning on about how assassins are poets and their victims their poems, should instead maybe fling herself headfirst down a plastic tube slide. Dampen her legendary noble face in a puddle waiting for her at the bottom. Then let Bob Saget introduce the next existential crises to rock this dreadfully boring 19th century period piece. Maybe then, this movie might make some aesthetic sense.

This said, there is still something slightly compelling about watching a film that simply doesn’t seem like it should have ever even existed. The notoriously meticulous Antonioni should not be making films that can draw such surface parallels to David Priors Sledgehammer or Doris Wishman’s A Night to Dismember. Not unless he also became infected with the sudden urge to film tank-top food fights and axe inflicted head bonks. But, regardless, it is kind of amusing to watch him slum it a little in embracing the washed-out world of VHS tape recording and all of its low budget baggage, presumably dreaming of a day that Oscar the Grouch would aid him in keeping his pants from falling down. Or at least inspire him to do something better than this

Or so I assume. There seems no other explanation for The Mystery of Oberwald’s bad television vibes or its cheaply rendered lifelessness. It’s almost as if all his energy was spent waiting by the mailbox for his Thank You Gifts to arrive and there was nothing left over for the movie. Maybe this payment simply never came and he thinks this absolves him of the slow drying mess he’s created here. In any case, I watched it, and its curiosity factor seemed just enough to pull me through to the end of its ghastly slow runtime. But in the end, I was only left with questions.

Why? What? Huh?

Making the perverse choice to record Oberwald directly onto video, it doesn’t take long for it to become very hard to reconcile what we are watching with anything that has anything whatsoever to do with Antonioni. There will be brief moments of gracefully rendered camera movements, as well as his talent for asymmetrical compositions that make us want to look closer. These will be a nice call backs to a better time in the director's career, but to what end? What exactly are we being made to look more closely at? How blurry does he want this to get?

Ultimately, these will only be momentary and empty flashes of the director we know. The rest of the time we can’t help but be put off by how unpleasant everything is to look at. It seems to lack all sense of grace, deliberately embracing an ugly modernity that would unfortunately become dated almost immediately. As a result, we can’t help but be pulled out of the moment every time we watch the zoom of a lowly camrecorder slowly approach the stony visage of Monica Vitti. Instead, it feels we should be inching closer to some looming playground embarrassment, and that the actress, instead of staring at foliage and droning on about how assassins are poets and their victims their poems, should instead maybe fling herself headfirst down a plastic tube slide. Dampen her legendary noble face in a puddle waiting for her at the bottom. Then let Bob Saget introduce the next existential crises to rock this dreadfully boring 19th century period piece. Maybe then, this movie might make some aesthetic sense.

This said, there is still something slightly compelling about watching a film that simply doesn’t seem like it should have ever even existed. The notoriously meticulous Antonioni should not be making films that can draw such surface parallels to David Priors Sledgehammer or Doris Wishman’s A Night to Dismember. Not unless he also became infected with the sudden urge to film tank-top food fights and axe inflicted head bonks. But, regardless, it is kind of amusing to watch him slum it a little in embracing the washed-out world of VHS tape recording and all of its low budget baggage, presumably dreaming of a day that Oscar the Grouch would aid him in keeping his pants from falling down. Or at least inspire him to do something better than this