← Back to Reviews

in

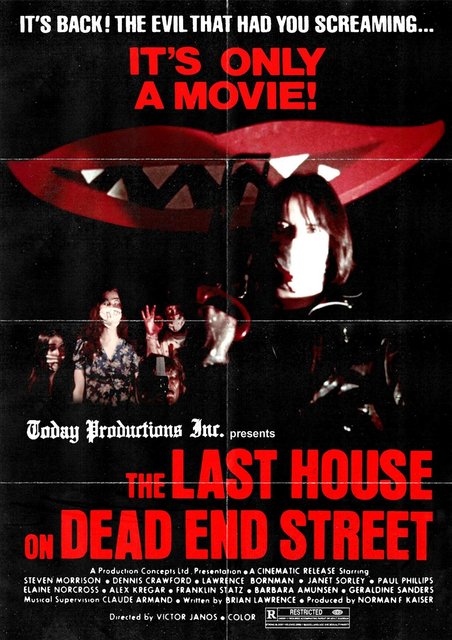

There are good reasons why I am inclined to think of movies in terms of what libation they most remind me of. How else to decide what from my fridge will be the most appropriate to drink in their company? For those films that are so light to the touch they seem to be filled with bubbles, itís likely the popping of champagne corks will soon frighten my cat as I put on LíAtalante. As for films inclined to show lives that amount to little more than a five dollar bottle of wine, for these a spell of Thunderbird inspired gut rot is most helpful. How else can one calibrate their Barfly headspace properly enough to climb up inside the Bukowski ****ted trousers of Mickey Rourke? You canít, of course, and youíve clearly watched it wrong if by the films conclusion you arenít stumbling out into the alley behind your house to sleep with the baby racoons that you have recently become friends with.

When it comes to Last House on Dead End Street though, it should be known beforehand that it offers no hope of quenching any kind of thirst. Best to simply show up already deplorable on drink since it is nothing but a half empty beer bottle being used as an ashtray. Filled with the remains of cigarettes half smoked by a lonely man on a sleepless night, it sits forgotten in a room, waiting to be mistakenly reached for when there is nothing left. The shock of all those cigarette ends soaked with old beer will not be pleasant as they land on your tongue, but in some ways they are precisely the beverage that should be paired with such a movie. The lingering flavor of ash carrying on and mingling with tomorrows hangover is the equivalent of how Last House cakes the senses, and refuses to be forgotten. It tastes like something as mundane and common as an untidy room, but for one moment manifests itself as something almost exotic. At least before you spit it out.

As a film, Last House seems to have been born from those moments before we find the aspirin or a toothbrush. It is sleepy and aching and empty, yet still also somewhat deranged from the night before. It presents itself to the audience as if it too is hungover and hasnít quite gotten over the fact that it has left the bed. Characters are often found sitting in chairs or shuffling through rooms, staring in a fog, the only conversation they can muster being the voiceovers grumbling away in their head like a headache. The colors that emanate from its images donít so much transmit from the screen, as dry and crack upon it. The sounds it makes are muffled like the arguing of neighbors through the walls. Everything seems presented to us from a distance. At least until those moments where it unleashes its violence upon us, and then the film becomes alive in ways that you might prefer it not to be. The color of blood, while seeming murky as if mixed with dirt, will still manage to glisten in a way that the rest of the film is much too dehydrated to ever do. The cries for help will be tinny and distorted, but will cut straight through whatever other dialogue is being mumbled, leaving audiences with no other option but to just sit there and gape. You are very aware you wonít be able to save anyone.

The violence will be so profound that it alone manages to give the entire movie some sense of a shape. From the ashes of their hungover mope, characters who have just been sitting around sneering about the world throughout the first half of the film, will suddenly rise up and move towards their victims as if they have purpose. Every thing about them now seems well rehearsed. They appear almost choreographed as they move closer. They will tend to their duties with a fervor hardly expected of such horrible slouches. Digging deeper and deeper into the entrails of their victims, they proceed undaunted by the blood or the screams. They are seemingly involved in an archeological excavation that will not stop until it reaches the center of the human body. Maybe the hope is simply to prove that there is no soul to be found inside of such a mess. They may even prove this as they hold what they find up to the camera as evidence. Nope, no soul here, their dead eyes will glint.

But is this enough? Anyone well versed in grindhouse films should be well aware that ugliness is as easy to create on film as giving someone the finger to their back. Going too far is even easier. Last House is guilty of both of these crimes in ways that, when simply describing what happens on screen, makes it seem like a movie that hardly has any more worth than some anti-social teens tantrum. Why donít you come take a mouthful of this **** sandwich, world! **** you, **** you, **** you, it seems to cry out before barricading itself in its room. And in many ways, this is actually very much a part of its boast. It is deliberately unapproachable because it has already decided it doesnít like you. It hates you for showing up to watch it, and it hates you even more if you think youíre too good for it. You canít possibly win with a film that has fallen so deeply into its own sense of self and societal loathing.

But make no mistake. Last House on Dead End Street is a very good film. What makes the ultimate difference here, and elevates what on first impulse seems like junk, into something that could legitimately be called art, is that somehow director Roger Watkins manages the impossible. He makes what seems little less than juvenile provocation actually frightening. Never before has splatter felt so soul shaking. Although it is not nearly as successful, the only comparable reference point in modern film is Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Like Hooperís exercise in human depravity, these films elevate what is little more than the crude actions of violent men, and turns them into something other worldly. The horror isnít really about the threat of death, but is much more about creating a surreal and dream like space in which such corporal abominations can occur in. The internal organs the actors hold up to the camera for investigation are like discoveries from a lost world. It just so happens that this lost world is inside all of us, just out of view, and this movie exists just to let us know how terrifyingly easy they are to discover.

By employing a cruddy cinema verite style in introducing the lives of these slum villains during the opening half hour, Watkins creates a very drab and unadorned base world from which he will launch the rest of the film into the blood-sunset violence of its built-to-spill conclusion. In the beginning, cameras are static. Characters seem to wander in frame aimlessly. Rooms are so dark and smoke filled figures are hard to make out. Dialogue is directionless. But then as the smell of violence rises in the air, the camera will suddenly begin to move with an eerie grace. Great care will be placed in how the rooms are lit (or over lit, or under lit). Atonal music will begin to clang. Characters appear from unexpected places, sometimes even banging holes through walls to make an appearance, other times breaking into dance at inappropriate moments. The difference in these two competing approaches is striking, and yet Watkins somehow will stitch these scenes of violence that appear to be transmitted in from another dimension, seamlessly into the Sunday morning blah of the surrounding film. They almost play like mirror images of those classic stories of alien abductions in the 1980ís. Some drunken yokel sobers up from his standard afternoon beer binge to find himself on an operating table, beneath strange lights, surrounded by inhuman faces holding up shining utensils. Except in this instance, it is not aliens but the hillbillies who are responsible for the kidnapping. As well as the upcoming surgery.

Like all nihilistic loud mouths, Watkins will of course not be able to resist attempts to blame his film on a corrupt modern world that would never dare to pay him any attention unless he was willing to sink to such vile displays. This wasnít a particularly compelling excuse when Deodato attempted it in 1980 for Cannibal Holocaust, and the fact that Watkins got there first is hardly commendable, even if he doesnít have the baggage of actually killing things and terrorizing native villages to justify his moral objection to violence. He does seem slightly more studied in his hatred towards society though, which gives his brutish philosophy, if not any reason to be contemplated seriously, a certain extra uneasiness. He comes across as a man who could possibly be just articulate enough to convince the sort of deadbeats that populate his world to do the horrible crimes he imagines. He was clearly able to convince others to appear in this film, which itself is something, considering at times it nearly seems to verge on the line of criminality itself.

With such a misanthropic world view at hand, Watkins doesnít dare clutter up his philosophizing with complicated plot mechnizations or character motivations. Everything is kept at a bare minimum in Last House. His gaze will keep its unblinking focus on the days following a mans release from prison, and his big plans to begin producing snuff films. There is no eureka moment. No need to make a great case for others to join him in his pursuit. It is simply presented as a matter of fact principal. Heís angry, the world is ****, and he believes he has something to show it. The presumption that the world wants what he has, will go unchallenged.

And this shouldnít be surprising, considering the way Watkins sees the world. In Last House, there is only him and his band of misfits, and those Watkins seems to view as the Haveís to his Have-Nots: the professional pornographers. No one else seems to exist or matter. The only time he will ever cut away from the dingy snuff world he has created, will be to show us the pampered lifestyle of these actually successful smut peddlers, as if simultaneously condemning and jealous of them. Just look at them laughing it up in their middle class luxury, drinking wine and eating cheese, their decadent lives being entertained by the sight of a humpback whipping a woman in blackface. Tra-la-la and please pass the brie. With such bourgeois atrocities as sadomasochistic minstrel pantomimes presumably being performed in the living rooms all across American suburbia, there is almost a feeling that Watkins is using this as a wedge issue to make the case that his penniless scumbags are some kind of working class heroes. Not because they are any better, but simply because of the fact they have been denied the chance of profiting off of their scumbaggery. What has white privilege ever given them, dammit!

At times the main character will fantasize about the stardom and money he believes he will be rewarded with for being so prescient about the value of real violence in film. Playing this leading role himself, it becomes easy to imagine that Watkins himself may have thought similarly about his unapologetic vision of a super violent American New Wave, and that the world would soon be his oyster. Itís definitely possible that his view of society was so debased that he truly believed Last House would put him within reach of the first rung on the ladder of success. But with this unholy mix of HG Lewisí dime store cynicism and a primal version of Ingmar Bergmanís existential terror, the result was of course never going to be anything but abject failure. Nothing this toxic could ever grant any one access to anything beyond a societal shunning, and so he would sadly never attain the luxury of having his very own humpbacked servant with a whip. Instead, after making this film, he would fall directly into the world of sex films and pornography, the very industry he had condemned as not being forward thinking enough to appreciate his auteurs eye for debasement. Such a step backward into oblivion makes it easy to conjure up images of him late in his failed career, sitting up alone at night, fuming at society while filling a beer bottle with one cigarette after another. One can only hope he never mistakenly took a sip, since such a taste could not help but bring him back to memories of his failure, and the strangely misery masterpiece it created.

The file digging continues. Another old write up I'm bringing back to life. It's definitely better than I remember, because I used to think of this as one of the worst.

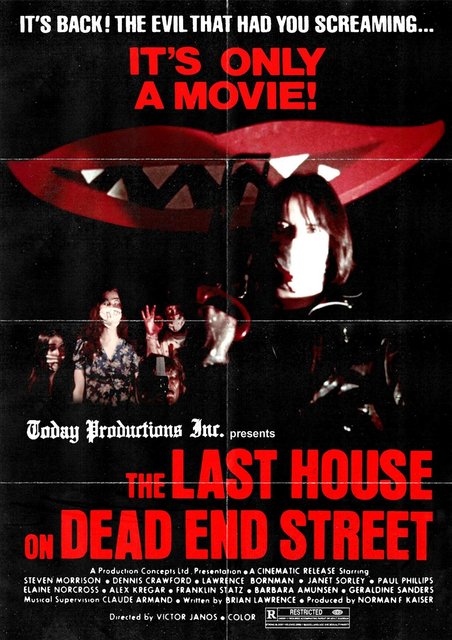

There are good reasons why I am inclined to think of movies in terms of what libation they most remind me of. How else to decide what from my fridge will be the most appropriate to drink in their company? For those films that are so light to the touch they seem to be filled with bubbles, itís likely the popping of champagne corks will soon frighten my cat as I put on LíAtalante. As for films inclined to show lives that amount to little more than a five dollar bottle of wine, for these a spell of Thunderbird inspired gut rot is most helpful. How else can one calibrate their Barfly headspace properly enough to climb up inside the Bukowski ****ted trousers of Mickey Rourke? You canít, of course, and youíve clearly watched it wrong if by the films conclusion you arenít stumbling out into the alley behind your house to sleep with the baby racoons that you have recently become friends with.

When it comes to Last House on Dead End Street though, it should be known beforehand that it offers no hope of quenching any kind of thirst. Best to simply show up already deplorable on drink since it is nothing but a half empty beer bottle being used as an ashtray. Filled with the remains of cigarettes half smoked by a lonely man on a sleepless night, it sits forgotten in a room, waiting to be mistakenly reached for when there is nothing left. The shock of all those cigarette ends soaked with old beer will not be pleasant as they land on your tongue, but in some ways they are precisely the beverage that should be paired with such a movie. The lingering flavor of ash carrying on and mingling with tomorrows hangover is the equivalent of how Last House cakes the senses, and refuses to be forgotten. It tastes like something as mundane and common as an untidy room, but for one moment manifests itself as something almost exotic. At least before you spit it out.

As a film, Last House seems to have been born from those moments before we find the aspirin or a toothbrush. It is sleepy and aching and empty, yet still also somewhat deranged from the night before. It presents itself to the audience as if it too is hungover and hasnít quite gotten over the fact that it has left the bed. Characters are often found sitting in chairs or shuffling through rooms, staring in a fog, the only conversation they can muster being the voiceovers grumbling away in their head like a headache. The colors that emanate from its images donít so much transmit from the screen, as dry and crack upon it. The sounds it makes are muffled like the arguing of neighbors through the walls. Everything seems presented to us from a distance. At least until those moments where it unleashes its violence upon us, and then the film becomes alive in ways that you might prefer it not to be. The color of blood, while seeming murky as if mixed with dirt, will still manage to glisten in a way that the rest of the film is much too dehydrated to ever do. The cries for help will be tinny and distorted, but will cut straight through whatever other dialogue is being mumbled, leaving audiences with no other option but to just sit there and gape. You are very aware you wonít be able to save anyone.

The violence will be so profound that it alone manages to give the entire movie some sense of a shape. From the ashes of their hungover mope, characters who have just been sitting around sneering about the world throughout the first half of the film, will suddenly rise up and move towards their victims as if they have purpose. Every thing about them now seems well rehearsed. They appear almost choreographed as they move closer. They will tend to their duties with a fervor hardly expected of such horrible slouches. Digging deeper and deeper into the entrails of their victims, they proceed undaunted by the blood or the screams. They are seemingly involved in an archeological excavation that will not stop until it reaches the center of the human body. Maybe the hope is simply to prove that there is no soul to be found inside of such a mess. They may even prove this as they hold what they find up to the camera as evidence. Nope, no soul here, their dead eyes will glint.

But is this enough? Anyone well versed in grindhouse films should be well aware that ugliness is as easy to create on film as giving someone the finger to their back. Going too far is even easier. Last House is guilty of both of these crimes in ways that, when simply describing what happens on screen, makes it seem like a movie that hardly has any more worth than some anti-social teens tantrum. Why donít you come take a mouthful of this **** sandwich, world! **** you, **** you, **** you, it seems to cry out before barricading itself in its room. And in many ways, this is actually very much a part of its boast. It is deliberately unapproachable because it has already decided it doesnít like you. It hates you for showing up to watch it, and it hates you even more if you think youíre too good for it. You canít possibly win with a film that has fallen so deeply into its own sense of self and societal loathing.

But make no mistake. Last House on Dead End Street is a very good film. What makes the ultimate difference here, and elevates what on first impulse seems like junk, into something that could legitimately be called art, is that somehow director Roger Watkins manages the impossible. He makes what seems little less than juvenile provocation actually frightening. Never before has splatter felt so soul shaking. Although it is not nearly as successful, the only comparable reference point in modern film is Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Like Hooperís exercise in human depravity, these films elevate what is little more than the crude actions of violent men, and turns them into something other worldly. The horror isnít really about the threat of death, but is much more about creating a surreal and dream like space in which such corporal abominations can occur in. The internal organs the actors hold up to the camera for investigation are like discoveries from a lost world. It just so happens that this lost world is inside all of us, just out of view, and this movie exists just to let us know how terrifyingly easy they are to discover.

By employing a cruddy cinema verite style in introducing the lives of these slum villains during the opening half hour, Watkins creates a very drab and unadorned base world from which he will launch the rest of the film into the blood-sunset violence of its built-to-spill conclusion. In the beginning, cameras are static. Characters seem to wander in frame aimlessly. Rooms are so dark and smoke filled figures are hard to make out. Dialogue is directionless. But then as the smell of violence rises in the air, the camera will suddenly begin to move with an eerie grace. Great care will be placed in how the rooms are lit (or over lit, or under lit). Atonal music will begin to clang. Characters appear from unexpected places, sometimes even banging holes through walls to make an appearance, other times breaking into dance at inappropriate moments. The difference in these two competing approaches is striking, and yet Watkins somehow will stitch these scenes of violence that appear to be transmitted in from another dimension, seamlessly into the Sunday morning blah of the surrounding film. They almost play like mirror images of those classic stories of alien abductions in the 1980ís. Some drunken yokel sobers up from his standard afternoon beer binge to find himself on an operating table, beneath strange lights, surrounded by inhuman faces holding up shining utensils. Except in this instance, it is not aliens but the hillbillies who are responsible for the kidnapping. As well as the upcoming surgery.

Like all nihilistic loud mouths, Watkins will of course not be able to resist attempts to blame his film on a corrupt modern world that would never dare to pay him any attention unless he was willing to sink to such vile displays. This wasnít a particularly compelling excuse when Deodato attempted it in 1980 for Cannibal Holocaust, and the fact that Watkins got there first is hardly commendable, even if he doesnít have the baggage of actually killing things and terrorizing native villages to justify his moral objection to violence. He does seem slightly more studied in his hatred towards society though, which gives his brutish philosophy, if not any reason to be contemplated seriously, a certain extra uneasiness. He comes across as a man who could possibly be just articulate enough to convince the sort of deadbeats that populate his world to do the horrible crimes he imagines. He was clearly able to convince others to appear in this film, which itself is something, considering at times it nearly seems to verge on the line of criminality itself.

With such a misanthropic world view at hand, Watkins doesnít dare clutter up his philosophizing with complicated plot mechnizations or character motivations. Everything is kept at a bare minimum in Last House. His gaze will keep its unblinking focus on the days following a mans release from prison, and his big plans to begin producing snuff films. There is no eureka moment. No need to make a great case for others to join him in his pursuit. It is simply presented as a matter of fact principal. Heís angry, the world is ****, and he believes he has something to show it. The presumption that the world wants what he has, will go unchallenged.

And this shouldnít be surprising, considering the way Watkins sees the world. In Last House, there is only him and his band of misfits, and those Watkins seems to view as the Haveís to his Have-Nots: the professional pornographers. No one else seems to exist or matter. The only time he will ever cut away from the dingy snuff world he has created, will be to show us the pampered lifestyle of these actually successful smut peddlers, as if simultaneously condemning and jealous of them. Just look at them laughing it up in their middle class luxury, drinking wine and eating cheese, their decadent lives being entertained by the sight of a humpback whipping a woman in blackface. Tra-la-la and please pass the brie. With such bourgeois atrocities as sadomasochistic minstrel pantomimes presumably being performed in the living rooms all across American suburbia, there is almost a feeling that Watkins is using this as a wedge issue to make the case that his penniless scumbags are some kind of working class heroes. Not because they are any better, but simply because of the fact they have been denied the chance of profiting off of their scumbaggery. What has white privilege ever given them, dammit!

At times the main character will fantasize about the stardom and money he believes he will be rewarded with for being so prescient about the value of real violence in film. Playing this leading role himself, it becomes easy to imagine that Watkins himself may have thought similarly about his unapologetic vision of a super violent American New Wave, and that the world would soon be his oyster. Itís definitely possible that his view of society was so debased that he truly believed Last House would put him within reach of the first rung on the ladder of success. But with this unholy mix of HG Lewisí dime store cynicism and a primal version of Ingmar Bergmanís existential terror, the result was of course never going to be anything but abject failure. Nothing this toxic could ever grant any one access to anything beyond a societal shunning, and so he would sadly never attain the luxury of having his very own humpbacked servant with a whip. Instead, after making this film, he would fall directly into the world of sex films and pornography, the very industry he had condemned as not being forward thinking enough to appreciate his auteurs eye for debasement. Such a step backward into oblivion makes it easy to conjure up images of him late in his failed career, sitting up alone at night, fuming at society while filling a beer bottle with one cigarette after another. One can only hope he never mistakenly took a sip, since such a taste could not help but bring him back to memories of his failure, and the strangely misery masterpiece it created.