Before I forget the idea, I wanted to put it out there. I also have to find it - I had something interesting written by Pauline Kael.

Any kind of document that talks about movies... Actually I have another one, Ray Carney on why movies aren't good anymore, and he has a lot of contacts with independent and mainstream filmmakers (John Cassavetes and Sidney Lumet).

I'll just paste it, and I'll put down the URL below.

http://people.bu.edu/rcarney/indievision/other.shtml

Why are Hollywood movies so bad? The best way to answer the question is simply to take you behind the scenes on a quick cook's tour of how movies are really made. I warn you. It's not a pretty picture.

The first thing you never want to forget about the movies in that–first , last and always–they are business deals put together to make a quick buck. To say the obvious, the goal is to take $7.50 out of as many pockets as possible. Everything is directed to that interest.

There was an interview in the last Saturday's Globe with Sydney Lumet that more or less sums up the current state of the art.

Lumet's comments are all the more telling in that they don't come from some wild-eyed radical, but from the ultimate Hollywood insider. Lumet has been making successful, money-making Hollywood movies for more than 40 years.

On the other hand, of course a Stalin movie would never really be made precisely because it would be controversial and would alienate blocks of viewers, and jeopardize profits.

What Hollywood is in favor of is not controversy, but pseudo-controversy. On the one hand, you want people to think that your movie is really new and different and controversial; but on the other, you don't want to actually create a disturbance. You don't want to force viewers really to have to think or to learn something. If you are dealing with politics in particular, the formula involves taking a topical issue–Watergate, Vietnam, the Holocaust–but making sure that it is situated at a certain distance from the average viewer's experience or knowledge.

Hollywood movies take our common-sense understandings and sell them back to us, with a slight change of clothes. It's a little like one of those MacDonald's Happy Meal promotions. You add a new spice or condiment or action figure to deep people's interest, but basically you give them the same fast food over and over again.

In terms of the production of these films, timidity is built into the system at every level. Movies originate as "deals"–business arrangements hashed out between producers, directors, writers, and a group of stars, in which the movie itself becomes an almost incidental after-thought: The real goal of each of the parties is to protect his or her financial interest, and to maximize the final product's "bankability."

In the service of doing that, the overriding goal is to secure a name star at any cost. When I talk to beginning directors, it's usually the first story they tell me: How they took their first script to a studio–sometimes a marvelous script–and were told the project could only get a green light if a particular "name" actor plays the lead–if Johnny Depp or Tom Hanks or Tom Cruise can be persuaded to do it–no matter how ludicrously inappropriate that particular choice might be for the role.

Then once a real "star" signs on to a production, the dynamics of the deal allow the star to demand as many rewrites as he or she wants until they are happy with the script.

I interviewed a director a few years ago who told an all too typical story that summarizes the situation. He had written a serious treatment of Black-White race relations in the fifties in the Deep South, and approached a studio to get it financed. To protect their interest, they said they would only take it on if Whoopi Goldberg played the lead. He thought that was the end of it, and that the film would never be made: Not only was she wildly inappropriate for the part, but he figured she would never agree to it. Well, for whatever reason, she did sign onto it. He thought he had died and gone to heaven. The only problem was that a few weeks before the shooting began she insisted that all of her scenes be rewritten. Seems she thought her character was too hard. It would ruin her image. She wanted her role made sweeter. Since she was a condition of the financing, of course he had to agree. I don't need to tell you the end of the story. One more sentimental Hollywood movie.

Even after a studio film has been scripted, cast, and shot, it's not immune from further mutilation. Virtually every Hollywood movie is audience-tested before it is released. If the preview audiences don't respond loudly and obviously enough, the film is reshot and re-edited until they do. As an example, Fatal Attraction actually had a fairly nuanced ending when it was first shot, but after audience testing, the ending was rewritten and re-filmed so that the Glen Close character was murdered in a horror movie gore fest.

In short, the goal is to make sure that the audience never has to work very hard, or be seriously challenged in any way. A movie you have to think about for a few day; or one you have to go back a see again to understand flunks the preview test by definition. That's why most Hollywood movies end up having morality-play plots, characters who can be divided into good or bad guys, and slam-bang happy endings where justice triumphs and all the problems are solved in the final five minutes.

These movies are the best roller-coaster rides ever made. You strap yourself into them. You undergo a few thrills and chills, a fake scare or two. And then it's all over and everything is OK again. You leave the theater no different from the way you went in.

* * *

Let me go on to the second point. If the movies are as bad as I am saying, and at least the people I talk to seem to agree that they are pretty awful, why is it so hard for non-Hollywood movies, the other movies, to get screened and known?

Going behind the scenes a little can perhaps help to explain why the alternative filmmaker is left out of the picture. You have to start with the fact that 99 percent of the movie houses in America are part of enormous theater chains. Sony, for example, owns and operates more than 700 screens in New England alone, and approximately 2000 screens from coast to coast.

One office rents and programs all of the movies for the entire chain. In the case of the Sony theaters, all of the movies for those 700 New England and 2000 national screens–are picked by three people in Secaucus, New Jersey. Do the results surprise you?

I want you to think about the job of those three programmers for a minute. I know the people who do this particular job. They're not bad folks. Their intentions are good. But what they need more than anything else is a steady, dependable stream of movies every week of the year. The basic fact of their existence is that they have to have something showing on a couple thousand otherwise blank screens every hour from noon to midnight, every day of the week. Those screens are like having a monster chained in your basement. You constantly need to feed it–to fill its maw–or it will destroy you. It takes an enormous number of films and prints to keep the whole thing going. Given this situation, is it any surprise that Sony and every other theater chain has a working relationship with certain major studios in which they play almost everything the studio releases? It's like General Motors establishing a relationship with a dependable parts supplier, or IBM having one with a chip maker.

Both the economics and the logistics of filling 2000 or more screens simultaneously leave the shoestring independent–the artist–out in the cold. In the first place, he or she simply can't afford to supply prints in the quantity required. Secondly, if an independent film doesn't have name stars and a major advertising campaign behind it, the theater chain programmer won't even risk playing it, since people won't come to a movie they haven't seen ads for or that doesn't have a big star in it. The independent filmmaker simply can't afford the advertising against the studios. A major studio release budgets between five and thirty million dollars for advertising alone; that's ten to a hundred times the entire budget of most alternative productions. The disproportion of economic resources is pretty stark. The entire budget of many alternative productions is what the studios spend on a single page ad in the Sunday New York Times.

Now the one way for the alternative filmmaker to break out of this vicious circle of neglect is to garner a rave review from a major critic at a major publication like Time Magazine or The New York Times. A review is the one available form of publicity that is free. And once in a while that happens. Janet Maslin–now–or Vincent Canby five or ten years ago could change film history with a single review. Jim Jarmusch and Spike Lee are examples of filmmakers who probably wouldn't be known today if Vincent Canby hadn't championed their first movies. The only problem is that this happens very rarely. In fact the opposite usually happens. Rather than bucking the tide and championing an alternative to Hollywood, most reviewers generally function as extensions of the studio publicity machinery.

There are many reasons why this is so, and I don't have time to go into them, but I simply want to mention two of the more troubling aspects of the relationship between film reviewers and Hollywood studios.

First, it's not a generally known fact that most of the leading film magazines are actually owned by the same people who own the Hollywood studios.

The second, even less known fact, is that most of what you read about films in most newspapers and magazines has, to some extent, been paid for by the studios–in the form of junkets provided to journalists. Each of the studios flies cadres of reviewers to New York or Los Angeles every week. They put them up in fancy hotels, pay for their meals, their bar tabs, and their other expenses–and arrange the interviews with the director and stars that you read in the newspaper or magazine. I would think it would be a clear journalistic conflict of interest to accept ongoing gifts and privileges from people you are supposed to be reporting on, but I have yet to see a single newspaper mention the film junkets in print.

* * *

There is much more to say about the potentially incestuous relationship of critics and Hollywood movies. But this is getting just too depressing. Even if I am in a church I don't want to sound too much like Jeremiah. So I want to conclude on a positive note, and suggest that there are wonderful alternative to Hollywood. Over the course of the past 30 years there have been many absolutely terrific film made. They just don't make it into the theater and the newspapers. But there are ways to see and celebrate the achievement of alternative films. Let me suggest four things you can do/not only see these movies, but to help make more of them possible. I list the steps in order of importance from more important to less:

In the first place, patronize independent movie theaters. There are a few movie theaters that are not part of chains, and they are almost the only places you can see non-mainstream movies. In Boston, the two most important independent commercial theaters are the Coolidge Corner in Brookline and the Brattle in Harvard Square. The Nickelodeon used to be good, but Sony bought it and that was the end of that. Loew's bought it back, but the damage had been done. It's now strictly a "fake indie" theatre. There are also two Boston non-commercial screening facilities that I highly recommend: Remis Auditorium at the Museum of Fine Arts, and the Harvard Film Archive in Cambridge.

There are some clunkers that play at all four of these locations, of course; but generally speaking, anything screening at The Coolidge Corner, the Brattle the MFA, or the Harvard Film Archive is probably better than anything else playing at any of the hundred chain-run movie theaters at the same time.

Second, if you want to give alternative work a try, go to a well-stocked video store (if you live in Boston, Videosmith is excellent), and do something directly the opposite of what most viewers do: Check out a recent movie you haven't heard anything about.

Be a market contrarian: if it stars Meryl Streep or Jack Nicholson don't rent it. Ever. If there are twenty copies of it on the shelf, walk past it. If there was a saturation ad campaign for it six months before, skip it. If it has a babe, a gun, or an exploding helicopter on the box, avoid it. Don't believe the hype. Every studio picture is packaged and pitched to make you feel you are not really alive unless you have seen it. It's a lie. You're only really alive, if you are not wasting your time on it. If you are doing something else.

On the other hand, if it is by a director you've never heard of, with unknown actors, a no-name releasing company, and has an unfamiliar title–it could be awful, but at least there's a chance it might be great.

(I'll give you another inside tip: one thing I look for is whether the director also wrote the movie–if the Beatles and Rolling Stones can write their own songs, a film artist should not have to hire a writer to make a movie.)

I've included a starter list of my own favorites on the sheet I distributed.

By the way, if you don't have a well-stocked video store down the street, you still have a chance to rent excellent videos. There are two video companies that rent non-Hollywood, alternative films by mail–for a small membership fee and a modest mailing charge. I highly recommend them (and guarantee that they haven't flown me around the country and put me up in a hotel to make me say it). They are called Facets and Home Film Festival, and their numbers are listed on the second page of the sheets you have. I have their catalogues here.

Third, whenever possible, cruise the Bravo networks if your cable system offers them. Bravo runs some real gems–many of which aren't available on video. It's almost axiomatic that nothing of real interest is going to appear on HBO, Showtime, The Movie Channel, of Cinemax, not to mention the networks or PBS.

Finally, if you want a book to guide your viewing, I'd recommend you be a contrarian in that too–stay away from the old standbys–especially Leonard Maltin's TV Movies, the one that everyone seems to buy. Most of the standard film indexes and encyclopedias don't even list the sort of movies I am recommending. But one book does. It is called: The TimeOut Guide to Film. (It's a British publication–doesn't that figure?) I highly recommend it.

Now, in good conscience, I want to end by issuing a consumer warning. As I've already said, the "other movies" are not Happy Meals or roller-coaster rides or feel-good entertainments. They are works of art, which means that they can be strange and off-putting if you are not ready for them. I can't guarantee that you will be pleased by every one of them. But they will make you think and feel in new ways. They will take you places that Hollywood movies don't ever dare to go.

But, for me at least, that's the fun of getting off the beaten path. While Hollywood offers formulas; these films are real adventures.

THE BEST INDEPENDENT FILMS YOU NEVER HEARD OF

(a beginner's guide to English-language films, any one of which is more important than Spike Lee's, Oliver Stone's, Steven Spielberg's, Joel and Ethan Coen's, and Quentin Tarantino's complete work)

Any kind of document that talks about movies... Actually I have another one, Ray Carney on why movies aren't good anymore, and he has a lot of contacts with independent and mainstream filmmakers (John Cassavetes and Sidney Lumet).

I'll just paste it, and I'll put down the URL below.

http://people.bu.edu/rcarney/indievision/other.shtml

Why are Hollywood movies so bad? The best way to answer the question is simply to take you behind the scenes on a quick cook's tour of how movies are really made. I warn you. It's not a pretty picture.

The first thing you never want to forget about the movies in that–first , last and always–they are business deals put together to make a quick buck. To say the obvious, the goal is to take $7.50 out of as many pockets as possible. Everything is directed to that interest.

There was an interview in the last Saturday's Globe with Sydney Lumet that more or less sums up the current state of the art.

Lumet's comments are all the more telling in that they don't come from some wild-eyed radical, but from the ultimate Hollywood insider. Lumet has been making successful, money-making Hollywood movies for more than 40 years.

On the other hand, of course a Stalin movie would never really be made precisely because it would be controversial and would alienate blocks of viewers, and jeopardize profits.

What Hollywood is in favor of is not controversy, but pseudo-controversy. On the one hand, you want people to think that your movie is really new and different and controversial; but on the other, you don't want to actually create a disturbance. You don't want to force viewers really to have to think or to learn something. If you are dealing with politics in particular, the formula involves taking a topical issue–Watergate, Vietnam, the Holocaust–but making sure that it is situated at a certain distance from the average viewer's experience or knowledge.

Hollywood movies take our common-sense understandings and sell them back to us, with a slight change of clothes. It's a little like one of those MacDonald's Happy Meal promotions. You add a new spice or condiment or action figure to deep people's interest, but basically you give them the same fast food over and over again.

In terms of the production of these films, timidity is built into the system at every level. Movies originate as "deals"–business arrangements hashed out between producers, directors, writers, and a group of stars, in which the movie itself becomes an almost incidental after-thought: The real goal of each of the parties is to protect his or her financial interest, and to maximize the final product's "bankability."

In the service of doing that, the overriding goal is to secure a name star at any cost. When I talk to beginning directors, it's usually the first story they tell me: How they took their first script to a studio–sometimes a marvelous script–and were told the project could only get a green light if a particular "name" actor plays the lead–if Johnny Depp or Tom Hanks or Tom Cruise can be persuaded to do it–no matter how ludicrously inappropriate that particular choice might be for the role.

Then once a real "star" signs on to a production, the dynamics of the deal allow the star to demand as many rewrites as he or she wants until they are happy with the script.

I interviewed a director a few years ago who told an all too typical story that summarizes the situation. He had written a serious treatment of Black-White race relations in the fifties in the Deep South, and approached a studio to get it financed. To protect their interest, they said they would only take it on if Whoopi Goldberg played the lead. He thought that was the end of it, and that the film would never be made: Not only was she wildly inappropriate for the part, but he figured she would never agree to it. Well, for whatever reason, she did sign onto it. He thought he had died and gone to heaven. The only problem was that a few weeks before the shooting began she insisted that all of her scenes be rewritten. Seems she thought her character was too hard. It would ruin her image. She wanted her role made sweeter. Since she was a condition of the financing, of course he had to agree. I don't need to tell you the end of the story. One more sentimental Hollywood movie.

Even after a studio film has been scripted, cast, and shot, it's not immune from further mutilation. Virtually every Hollywood movie is audience-tested before it is released. If the preview audiences don't respond loudly and obviously enough, the film is reshot and re-edited until they do. As an example, Fatal Attraction actually had a fairly nuanced ending when it was first shot, but after audience testing, the ending was rewritten and re-filmed so that the Glen Close character was murdered in a horror movie gore fest.

In short, the goal is to make sure that the audience never has to work very hard, or be seriously challenged in any way. A movie you have to think about for a few day; or one you have to go back a see again to understand flunks the preview test by definition. That's why most Hollywood movies end up having morality-play plots, characters who can be divided into good or bad guys, and slam-bang happy endings where justice triumphs and all the problems are solved in the final five minutes.

These movies are the best roller-coaster rides ever made. You strap yourself into them. You undergo a few thrills and chills, a fake scare or two. And then it's all over and everything is OK again. You leave the theater no different from the way you went in.

* * *

Let me go on to the second point. If the movies are as bad as I am saying, and at least the people I talk to seem to agree that they are pretty awful, why is it so hard for non-Hollywood movies, the other movies, to get screened and known?

Going behind the scenes a little can perhaps help to explain why the alternative filmmaker is left out of the picture. You have to start with the fact that 99 percent of the movie houses in America are part of enormous theater chains. Sony, for example, owns and operates more than 700 screens in New England alone, and approximately 2000 screens from coast to coast.

One office rents and programs all of the movies for the entire chain. In the case of the Sony theaters, all of the movies for those 700 New England and 2000 national screens–are picked by three people in Secaucus, New Jersey. Do the results surprise you?

I want you to think about the job of those three programmers for a minute. I know the people who do this particular job. They're not bad folks. Their intentions are good. But what they need more than anything else is a steady, dependable stream of movies every week of the year. The basic fact of their existence is that they have to have something showing on a couple thousand otherwise blank screens every hour from noon to midnight, every day of the week. Those screens are like having a monster chained in your basement. You constantly need to feed it–to fill its maw–or it will destroy you. It takes an enormous number of films and prints to keep the whole thing going. Given this situation, is it any surprise that Sony and every other theater chain has a working relationship with certain major studios in which they play almost everything the studio releases? It's like General Motors establishing a relationship with a dependable parts supplier, or IBM having one with a chip maker.

Both the economics and the logistics of filling 2000 or more screens simultaneously leave the shoestring independent–the artist–out in the cold. In the first place, he or she simply can't afford to supply prints in the quantity required. Secondly, if an independent film doesn't have name stars and a major advertising campaign behind it, the theater chain programmer won't even risk playing it, since people won't come to a movie they haven't seen ads for or that doesn't have a big star in it. The independent filmmaker simply can't afford the advertising against the studios. A major studio release budgets between five and thirty million dollars for advertising alone; that's ten to a hundred times the entire budget of most alternative productions. The disproportion of economic resources is pretty stark. The entire budget of many alternative productions is what the studios spend on a single page ad in the Sunday New York Times.

Now the one way for the alternative filmmaker to break out of this vicious circle of neglect is to garner a rave review from a major critic at a major publication like Time Magazine or The New York Times. A review is the one available form of publicity that is free. And once in a while that happens. Janet Maslin–now–or Vincent Canby five or ten years ago could change film history with a single review. Jim Jarmusch and Spike Lee are examples of filmmakers who probably wouldn't be known today if Vincent Canby hadn't championed their first movies. The only problem is that this happens very rarely. In fact the opposite usually happens. Rather than bucking the tide and championing an alternative to Hollywood, most reviewers generally function as extensions of the studio publicity machinery.

There are many reasons why this is so, and I don't have time to go into them, but I simply want to mention two of the more troubling aspects of the relationship between film reviewers and Hollywood studios.

First, it's not a generally known fact that most of the leading film magazines are actually owned by the same people who own the Hollywood studios.

The second, even less known fact, is that most of what you read about films in most newspapers and magazines has, to some extent, been paid for by the studios–in the form of junkets provided to journalists. Each of the studios flies cadres of reviewers to New York or Los Angeles every week. They put them up in fancy hotels, pay for their meals, their bar tabs, and their other expenses–and arrange the interviews with the director and stars that you read in the newspaper or magazine. I would think it would be a clear journalistic conflict of interest to accept ongoing gifts and privileges from people you are supposed to be reporting on, but I have yet to see a single newspaper mention the film junkets in print.

* * *

There is much more to say about the potentially incestuous relationship of critics and Hollywood movies. But this is getting just too depressing. Even if I am in a church I don't want to sound too much like Jeremiah. So I want to conclude on a positive note, and suggest that there are wonderful alternative to Hollywood. Over the course of the past 30 years there have been many absolutely terrific film made. They just don't make it into the theater and the newspapers. But there are ways to see and celebrate the achievement of alternative films. Let me suggest four things you can do/not only see these movies, but to help make more of them possible. I list the steps in order of importance from more important to less:

In the first place, patronize independent movie theaters. There are a few movie theaters that are not part of chains, and they are almost the only places you can see non-mainstream movies. In Boston, the two most important independent commercial theaters are the Coolidge Corner in Brookline and the Brattle in Harvard Square. The Nickelodeon used to be good, but Sony bought it and that was the end of that. Loew's bought it back, but the damage had been done. It's now strictly a "fake indie" theatre. There are also two Boston non-commercial screening facilities that I highly recommend: Remis Auditorium at the Museum of Fine Arts, and the Harvard Film Archive in Cambridge.

There are some clunkers that play at all four of these locations, of course; but generally speaking, anything screening at The Coolidge Corner, the Brattle the MFA, or the Harvard Film Archive is probably better than anything else playing at any of the hundred chain-run movie theaters at the same time.

Second, if you want to give alternative work a try, go to a well-stocked video store (if you live in Boston, Videosmith is excellent), and do something directly the opposite of what most viewers do: Check out a recent movie you haven't heard anything about.

Be a market contrarian: if it stars Meryl Streep or Jack Nicholson don't rent it. Ever. If there are twenty copies of it on the shelf, walk past it. If there was a saturation ad campaign for it six months before, skip it. If it has a babe, a gun, or an exploding helicopter on the box, avoid it. Don't believe the hype. Every studio picture is packaged and pitched to make you feel you are not really alive unless you have seen it. It's a lie. You're only really alive, if you are not wasting your time on it. If you are doing something else.

On the other hand, if it is by a director you've never heard of, with unknown actors, a no-name releasing company, and has an unfamiliar title–it could be awful, but at least there's a chance it might be great.

(I'll give you another inside tip: one thing I look for is whether the director also wrote the movie–if the Beatles and Rolling Stones can write their own songs, a film artist should not have to hire a writer to make a movie.)

I've included a starter list of my own favorites on the sheet I distributed.

By the way, if you don't have a well-stocked video store down the street, you still have a chance to rent excellent videos. There are two video companies that rent non-Hollywood, alternative films by mail–for a small membership fee and a modest mailing charge. I highly recommend them (and guarantee that they haven't flown me around the country and put me up in a hotel to make me say it). They are called Facets and Home Film Festival, and their numbers are listed on the second page of the sheets you have. I have their catalogues here.

Third, whenever possible, cruise the Bravo networks if your cable system offers them. Bravo runs some real gems–many of which aren't available on video. It's almost axiomatic that nothing of real interest is going to appear on HBO, Showtime, The Movie Channel, of Cinemax, not to mention the networks or PBS.

Finally, if you want a book to guide your viewing, I'd recommend you be a contrarian in that too–stay away from the old standbys–especially Leonard Maltin's TV Movies, the one that everyone seems to buy. Most of the standard film indexes and encyclopedias don't even list the sort of movies I am recommending. But one book does. It is called: The TimeOut Guide to Film. (It's a British publication–doesn't that figure?) I highly recommend it.

Now, in good conscience, I want to end by issuing a consumer warning. As I've already said, the "other movies" are not Happy Meals or roller-coaster rides or feel-good entertainments. They are works of art, which means that they can be strange and off-putting if you are not ready for them. I can't guarantee that you will be pleased by every one of them. But they will make you think and feel in new ways. They will take you places that Hollywood movies don't ever dare to go.

But, for me at least, that's the fun of getting off the beaten path. While Hollywood offers formulas; these films are real adventures.

THE BEST INDEPENDENT FILMS YOU NEVER HEARD OF

(a beginner's guide to English-language films, any one of which is more important than Spike Lee's, Oliver Stone's, Steven Spielberg's, Joel and Ethan Coen's, and Quentin Tarantino's complete work)

Basic training:

Vince Gallo, Buffalo 66

Tom Noonan, What Happened Was, The Wife (Noonan is the greatest living American director)

Ken Loach, Raining Stones

Su Friedrich, Sink or Swim, Rules of the Road

Gillian Armstrong, My Brilliant Career, The Last Days of Chez Nous

Charles Burnett, Killer of Sheep, To Sleep with Anger

Caveh Zahedi, A Little Stiff

Mike Leigh, Abigail's Party, High Hopes, Life is Sweet, The Short and Curlies

Sean Penn, Indian Runner

John Korty, The Crazy Quilt, Funnyman, Riverrun

Shirley Clarke, Portrait of Jason

Les Blair, Bad Behavior

Alison Anders, Gas, Food, Lodging

Elaine May, The Heartbreak Kid, Mikey and Nicky

John Cassavetes, Shadows, Minnie and Moskowitz, A Woman Under the Influence

Jane Spencer, Little Noises

Claudia Weill, Girlfriends

Harry Hook, The Kitchen Toto

Michael Almareyda, Another Girl, Another Planet, The Rocking Horse Winner, Sundance

Milton Moses Ginsberg, Coming Apart

Jim Jarmusch, Stranger than Paradise, Mystery Train

Strictly for the more daring:

Bruce Conner, Marilyn Times Five, Report, A Movie, The Rose

Todd Haynes, Safe, Superstar

Edmund Elias Merhige, Begotten

David Blair, Wax, The Discovery of Television Among the Bees

Mark Rappaport, The Scenic Route, Local Color

Alan Clarke, Rita, Sue and Bob Too, or anything else you can get by him

John Cassavetes, Faces, Husbands, The Killing of a Chinese Bookie, Opening Night, Love Streams

Michael Almereyda, Twister, Another Girl, Another Planet

Jon Jost, Bell Diamond, Last Chants for a Slow Dance

Mike Leigh, Bleak Moments, Meantime, Grown Ups, Kiss of Death, Hard Labor

Robert Kramer, Ice, Milestones, Route One, Starting Point

Barbara Loden, Wanda

Paul Morrissey, Trash, Flesh

Rick Schmidt, Morgan's Cake

Michael Radford, Another Time, Another Place

Richard Lowenstein, Dogs in Space

Thomas Vinterberg, The Celebration

Lars von Trier, Breaking the Waves

Last edited by matt72582; 12-23-15 at 06:43 PM.

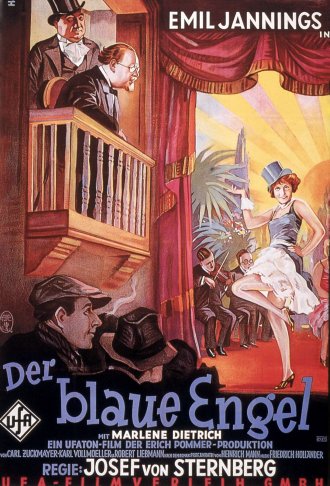

The Blue Angel (1930)

The Blue Angel (1930)

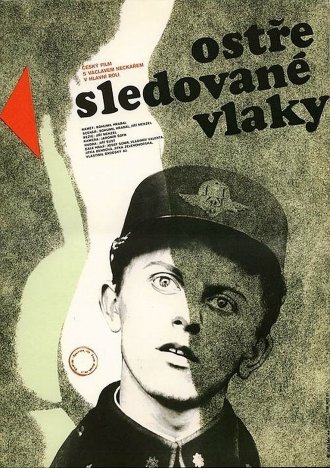

Closely Observed Trains (1966)

Closely Observed Trains (1966)

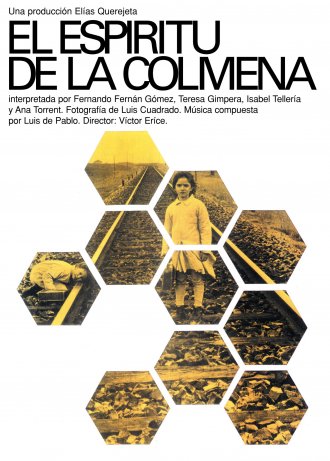

The Spirit of the Beehive (1973)

The Spirit of the Beehive (1973)

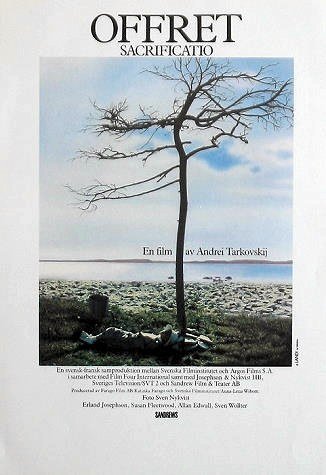

The Sacrifice (1986)

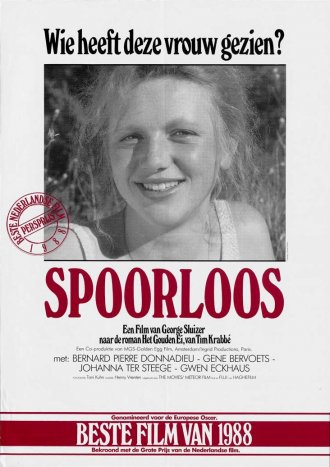

The Sacrifice (1986) The Vanishing (1988)

The Vanishing (1988)