Takashi Miike: Or how Extreme Violence is Japans favourite export

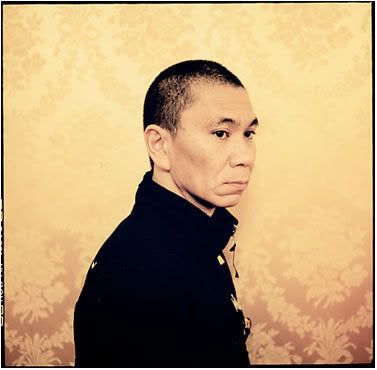

It’s not an outlandish statement to suggest that any fan of East Asian Cinema has heard of Miike. Undoubtedly an auteur and one of the most productive men working in cinema today, yet for all the eclectic films within his oeuvre, exposure to them abroad is surprisingly restricted. Arguably this is in a bid to market him predominantly as an ‘Extreme’ director. His name has almost become synonymous with genre, and with more than enough elements to substantiate the claim, it’s justified but is this facet of his work exploited in a bid to use his name as an anchor to films with the prescribed expectations of ‘Extreme Cinema’? Why is it only his films with focus on Yakuza and violence are widely distributed and his existential, art and family films not? Chris Desjardins rightly observes the apparent critical need to pigeonhole Miike into the constraints of his more ‘extreme’ offerings, referring to him as catering for the lowest common denominator, yet said critics avoid noting the frequent and balanced spectrum of complex emotions and attention Miike displays to character development (2005, p.189). Now that Miike has not only physically crossed into America with a cameo in Tarantino produced ‘gorno’ Hostel (Roth, 2005) (the favour returned with Tarantino’s appearance in Miike’s Sukiyaki Western: Django (2007)), but he has also had his own One Missed Call (2003) bastardised in the Hollywood remake fad. With his increasing presence in the West, should we not be looking further into films of this fascinating auteur with DVD access to his best and un-released films Izo (2004) and The Bird People in China (1998)?

The films of Miike occupy a specific point in Japanese film history. To begin with there’s the avant-garde movement. It rebelled against the homogenising and restrictive practices of Japan’s corporations, seeking an alternative democratic and liberating space. Released from the constraints of a hierarchal studio system and conservative social mores its goal was allowing freedom of expression to flourish (Standish, 2005, p.331). These avant-garde filmmakers, however, belong to the post-defeat Anpo generation of student activists. Standish places Miike into the post-moral sensibility of filmmaking. Here is an advanced consumer capitalism, where heterogeneity and difference is privileged as liberating, thus there is little to transgress and seemingly little to rebel against (2005, p.332). The films of Miike directly herald the millennial approach of a rootless Asian society; he examines the damaged psyches of dispossessed characters, exploring the plights of even the most monstrous with a combination of objectivity and compassion. Despite his Western reception as an ‘extreme’ director, it’s apparent that his movies are highly motivated by a social awareness but much of this is lost in the West. Many of his widely released films demonstrate his ability to encapsulate the cultural, economical and psychological reverberations from the collision of the Japanese and Chinese underworlds (Desjardins, p.190, 2005). As Orientalism suggests the generalisation of East Asians, the cultural friction between Japan and China is almost irrelevant to Western viewers, leaving primarily good guys and bad guys. Even his representations and open mindedness are removed from their context of cultural liberation, Tony Rayns observes that no straight director has introduced more gay elements into his film, or shown gay sex with such gusto (2000, p.30) yet these become elements of his extremity or otherness.

On the outside, Izo would seem as an easy sell; the combination of two of the strongest creative forces in contemporary Japan- Miike and Takeshi Kitano. Tom Mes (2005, para.1) even goes as far as calling this a dream team match-up; creating ripples by means of casting choices was very much the intention of the group of investors backing the project; hoping to attract a general audience to a film whose appeal might otherwise have been limited. The film unravels in a similar manner to The Holy Mountain (Jodorowsky, 1973), displaying the trajectory of one man in an existential crisis. The film offers a bricolage, not only of the fictional diegetic and documentary footage but of Japanese iconography from the Yakuza to the feudal Japan swords and sandal films, such as Lone Wolf and Cub (Misune, 1972) - even to the extent of utilising a worn Grindhouse style stock. As the film attacks, both literally and metaphorically, the ideological state apparatus inherent in Japanese society it also observes the nature of humanity. Although the cultural capital to observe the contextual relevance isn’t readily available to a Western audience, the existential observations extend universally. So why has Izo, a film that has Miike exploring history and humanity, something similar to Farewell My Concubine (Kaige, 1993) for an active audience, not been released here?

Admittedly some of the blame for its cold fan reception may lie on the subbing on available copies; at times inconsistent and it’s extremely heavy handed in making almost every utterance appear as a philosophical statement. Mes even argues that a result of this, Izo is protracted and repetitive and that as a result of this its message becomes heavy, ponderous and perhaps even, to use that most lazy of adjectives, pretentious (2005, para.5). A more fluid and comprehensive translation would surely widen the appeal, especially when considered that the reoccurring singings of Kazuki Tomokawa are left un-subbed; the lyrics from the “Screaming Philosopher” would undoubtedly provide some further insight to the proceedings. But let’s remain with what we have, the violence and sexuality is on the same level of perversion as Visitor Q (Miike, 2001); Izo kills his mother, ****s the physical embodiment of Mother Nature, urinates on religion and defiles almost every sanctity of society from marriage to school. Metaphorical nature not withstanding, the violence is, in fact, the primary narrative of the film. For all intents and purposes, this is one of Miike’s most extreme films, which would lead one to believe it as prime for a Tartan release under their ‘Extreme’ banner. In a comparison against Ichi the Killer (Miike, 2001), which similarly deals with copious violence, Mes suggests they pose genuine and fundamental questions about our relationship to violence. Ichi the Killer is how we deal with its depiction on a personal level thus extending out of a cultural context; Izo, however, is how we relate to it collectively (2005, para.9). As a result Izo is intrinsically linked to the cultural state of Japan and the relevance of the violence is harder to decode for a Western viewer, leaving a film where violence is the narrative and little understanding of its relevance. George Clark states (2004, para.16); Izo is the personification of negation, a contradiction that emerged from Japan's perfectly ordered society. Izo is at once a philosophical treatise on the perpetual existence of evil and a carnivorous rampage through the male psyche.

The Bird People in China is the biggest wrench in the Miike oeuvre when marketing Miike abroad. Mes and Sharp (2005, p.182) observe this as a turning point in Miike’s career where he moved away from the preconception of him as a V-cinema yakuza film director. With The Bird People in China he continues elements seen in Rainy Dog (Miike, 1997) but creates a beautifully shot, humorous fantasy film. By many means, it’s a polar opposite of the grotesqueness in his other films. I’d hope that the reason its release hasn’t happened isn’t through lack of faith in the audience, the cultural conflict of two Japanese men in China could relate to the Orientalism prescription of Western audiences not being able to accurately distinguish the two cultures. The more logical reason would be the contradiction it throws between the current notions of Miike’s work. One seeing a Miike film has now gained a set of preconceived opinions regarding what they expect to see and The Bird People in China would simply not cater for this diversity, despite Miike offering at least one flair of violence it’s pretty much absent. There’s trouble enough that Hollywood feels the need to remake East Asian cinema for their own consumption but the fact this gem hasn’t seen a release is far more surprising than Izo, considering the fact it is one of Miike’s most accessible works and of greater scope and scale then anything before it (Mes & Sharp, 2005, p.188).

Despite its accessibility, it does still rely on cultural capital, although most Western viewers should be able to decode the laid out culture clash, to the extent that an Orientalist critique doesn’t prevent Westerners reading this basic narrative structure. On a basic linguistic level, the subtitles don’t indicate the language barrier between each culture, the multiple languages appearing a single English translation. To further the perplexity of this films lack of release is Mes’ observations on the film, it doesn’t aim to criticise Japanese society or its people as a whole, more over the lack of imagination that can result in living in that society (2004, p.133). Again, the film offers a general message that can be appreciated regardless of cultural difference, however much of its presentation is through cultural icons. Despite elements with potential to extend past its origin, it’s still firmly rooted within East Asia.

Even within Miike’s selective Western releases, there is already a considerable fluctuation in style and content- from the ‘serious’ character driven Audition (1999) (Desjardins, p.194, 2005); to the absurd musical Happiness of the Katakuris (2001); through to the family superhero adventure of Zebraman (2004) (‘family’ being a somewhat oddly used description for a film where the protagonist’s daughter is a prostitute); and finally the cinema verite stylised Visitor Q. Within all these there is some degree of transgression in a Western perception regarding genre and sexuality but combined with elements that provide a distinct vision of Miike. In turn, the strategic choice of released titles allows him to be pigeonholed under Tartan’s label of ‘Asian Extreme’. Perhaps it can be traced more towards Western audience desires, if they want ‘art’ there’s the strong presence of Kurosawa or Ozu, but the hankering for contemporary Asian cinema stems to the desire to view extreme visceral reactions provoked by the consequences of the conflating images of sex and violence (McRoy, 2005, p.16 citing Goldberg n.d.). With such a genre already set, to the point it is being directly used as influence for Hollywood, do audiences care for Japanese existentialism or the clashing of cultures they know little of? The answer would, at this time, appear to be not; unless of course they are back grounded to a relatable gangster narrative or hidden under nauseating imagery; as is the case of several of Miike’s already released films. Take Audition its undertones are relative to the viewer’s cultural capital, demonstrating a dichotomy of comparative appeal. For national audiences it offers a uniquely Japanese story of gender-related male anxieties, however Western audiences, in Myoshi’s (1989, cited by Hantke, 2005, p.62) terms can ‘domesticate or neutralise the exoticism of the text’, hence providing structural similarities Western audiences can relate to late capitalist economies (Hantke, 2005, p.62). It’s seems a shame that the notion of the auteur is being manipulated in such a way as to disguise the true creativity of Miike. But until ‘Extreme Asian Cinema’ begins its inevitable decline, time will come when his other films are released and marketed under his established reputation. Certainly, a different kind of ‘shock’ can be anticipated.

*As a disclaimer, this shouldn’t be viewed as a scathing critique of Tartan, who provides a considerably inclusive distribution of Asian cinema, more a suggestive reading of Western consumption.

).

).

I'm in two minds over whether I'll ever get around to seeing a Miike film - keep meaning to see Ichi the Killer first, but I can never be bothered looking for a rental and buying it seems a bit much (those concerns are slightly lower than the violence, although it sounds pretty brutal even for me) However, I noticed that Sukiyaki Western Django is coming up in a film festival next month and I'm thinking of checking it out.

I'm in two minds over whether I'll ever get around to seeing a Miike film - keep meaning to see Ichi the Killer first, but I can never be bothered looking for a rental and buying it seems a bit much (those concerns are slightly lower than the violence, although it sounds pretty brutal even for me) However, I noticed that Sukiyaki Western Django is coming up in a film festival next month and I'm thinking of checking it out.